Needs to be Fair, Followed by Trials of Pro-Ouattara Commanders

The upcoming trial in Côte d’Ivoire of the former Ivorian first lady Simone Gbagbo for crimes against humanity could be a pivotal moment for justice. However, for the trial to be meaningful to victims, it must be credible, fair, and followed by other trials that target high-level rights abusers from both sides of the 2010-2011 post-election crisis.

Human rights groups acting on behalf of victims have refused to participate in Simone Gbagbo’s trial, scheduled to begin on May 31, 2016. They have cited an incomplete investigation into her role in abuses and breaches of Côte d’Ivoire’s criminal procedure in the preparations for the trial.

“Simone Gbagbo’s trial – the first in Côte d’Ivoire for crimes against humanity– should be an opportunity for victims of pro-Gbagbo forces to learn the truth about her alleged role in abuses,” said Jim Wormington, West Africa researcher at Human Rights Watch. “But unless the trial is credible and fair, the hopes of victims will be short-lived.”

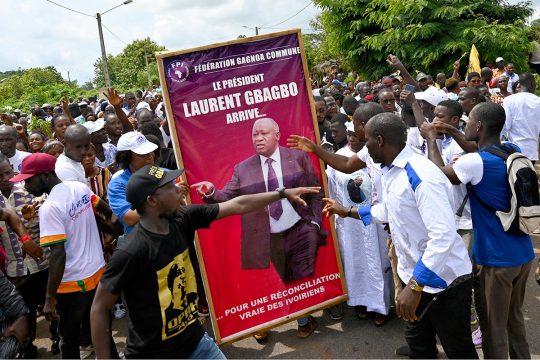

The post-election crisis stemmed from the refusal of then-president Laurent Gbagbo to cede power to the current president, Alassane Ouattara, following the November 2010 presidential elections. Gbagbo’s refusal to accept the election outcome was followed by violence and eventually a resumption of armed conflict. Between December 2010 and May 2011, at least 3,000 civilians were killed and more than 150 women were raped, with serious human rights violations committed by both sides.

Simone Gbagbo will be tried by Côte d’Ivoire’s highest criminal court (Cour d’Assises) for crimes against humanity and war crimes. The prosecution alleges that during the post-election crisis she participated in a “crisis committee” consisting of leaders from her husband’s political party and key government ministers that planned and organized abuses against Ouattara supporters to maintain her husband in power at all costs.

Simone Gbagbo at the Palace of Justice in Abidjan on December 26, 2014. © 2014 Reuters

Simone Gbagbo, who has been in custody in Côte d’Ivoire since April 2011, has also been indicted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for crimes against humanity during the post-election crisis. The ICC trial of her husband, former president Laurent Gbagbo, began January 28, 2016 in The Hague.

Côte d’Ivoire has so far refused to transfer Simone Gbagbo to the ICC. ICC judges in December 2014 and May 2015 rejected the government’s request for Ivorian courts to retain jurisdiction over Simone Gbagbo’s case, concluding that at the time the investigation into her role in human rights crimes had not made sufficient progress. These decisions mean that Cote d’Ivoire remains obligated to surrender Simone Gbagbo to The Hague.

The Ivorian government’s position remains that since national courts will try Simone Gbagbo for the same crimes that she has been charged with at the ICC, her case should remain in Côte d’Ivoire. Indeed, in April 2015 President Ouattara said that all future trials related to the post-election crisis would occur in national courts.

Several Ivorian officials told Human Rights Watch that the upcoming trial will demonstrate to the ICC that Simone Gbagbo can be fairly tried in Ivorian courts. However, the International Federation for Human Rights (Fédération Internationale des Ligues des Droits de l'Homme, FIDH) and two prominent Ivorian human rights groups, who are representing victims of the post-election crisis in national proceedings, have decided not to participate in the trial. In a public statement, FIDH said it had grave concerns that the investigation against Simone Gbagbo had been completed prematurely, and would not give victims a full picture of the role allegedly played by Simone Gbagbo in the abuses of the post-election crisis.

This is the second trial in Cote d’Ivoire for Simone Gbagbo. She was convicted in March 2015 for offenses against the state during the post-election crisis and sentenced to 20 years in prison. A key criticism of those proceedings was the lack of evidence presented linking her and other political leaders to violence by their supporters. Although Gbagbo will now stand trial for her role in human rights abuses, the principal challenge for the prosecution will be identifying evidence to tie her to the killings, rape, and other abuses by pro-Gbagbo forces.

The beginning of the trial comes amid ostensible progress in investigations for crimes committed during the post-election crisis, including the indictment of several high-level commanders from pro-Ouattara forces by Côte d’Ivoire’s Special Investigative and Examination Cell.

However, the government has not yet enacted several vital legal reforms scheduled to be carried out during President Ouattara’s first term in office, which ended in November 2015. Urgently needed reforms include a system to protect witnesses from reprisals and amendments to the criminal procedure code to require judges to provide reasons for their decisions and grant defendants a right of appeal.

Some commentators also allege that Simone Gbagbo’s trial is a sign that President Ouattara’s government ultimately intends to prosecute only crimes by pro-Gbagbo forces. President Ouattara has rejected this criticism, and said after his October reelection that: “Justice must be equal for all. We need to avoid impunity.”

To turn this rhetoric into reality, the Ivorian government should maintain support for impartial and independent investigations into crimes committed during the 2010-2011 conflict, and ensure that prosecutors and investigating judges are given the time and resources they need to finish their investigations. Courts should ensure that the right of victims to participate in the proceedings are respected.

“Five years after the post-election crisis, Cote d’Ivoire is entering a critical phase in the fight against impunity,” Wormington said. “The government should support the Ivorian judiciary’s efforts to complete investigations and conduct credible trials against those responsible for crimes from both sides.”

The article is published by Human Rights Watch