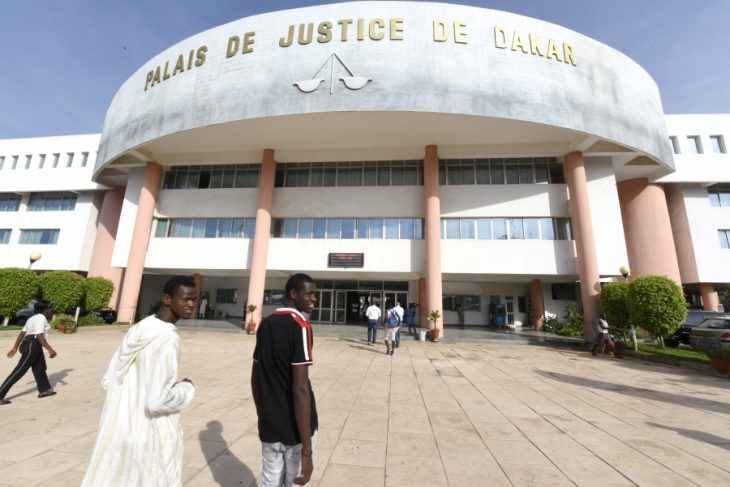

The May 30 conviction of former Chadian president Hissène Habré for crimes against humanity and war crimes committed under his rule “shows African countries are well able to try perpetrators of mass crimes in Africa, if they have the will to do so,” says Florent Geel, head of the Africa desk at the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). Habré, who has been living in exile in Senegal since 1990, was sentenced to life in prison by the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC), a special court sitting in Dakar.

JusticeInfo: What is the importance of this judgment for the world, and for Africa in particular?

Florent Geel: The judgment against Hissène Habré shows the whole world that an African country, Senegal, with a mandate from the African Union, can try a suspected perpetrator of mass crimes, in fact a former head of State, on African soil. It shows African countries are perfectly capable of living up to their responsibility to try mass criminals in Africa if the political will is there. This judgment can open a new era for Africa if African States assume their responsibilities. The second lesson is that even 20 years after the events, there can still be justice and justice can still win.

JusticeInfo: Can this judgment help strengthen democracy on a continent still marked by coups and often violent conflicts around elections?

FG: Aspiring putschists and other mass criminals, whether at the head of armed groups or of a State should now take note: if they commit crimes, they are likely to end their days in jail. Malian putschist Aya Sanogo is awaiting his judgment, Moussa Dadis Camara in Guinea should soon be brought to justice for his responsibility in the massacre of September 28, 2009, Côte d'Ivoire still needs to hold credible trials to turn the page of its post-election crisis…

JusticeInfo: But the positions of African leaders vary widely on how to end impunity for some of them…

FG: The Hissène Habré trial shows we are at a crucial moment of history in Africa: either impunity will be reduced through the political will of States that have now the means to do so, allowing Africa to enter a new age of justice and responsibility; or a few heads of State will continue to organize their own impunity, holding back the whole continent, by using for example the Malabo Protocol, which provides for an African Criminal Court to compete with the International Criminal Court (ICC) but also immunity/impunity for heads of State and government and their families. So you see, they are not at all in tune with the thirst for justice of the African people, especially the youth.

JusticeInfo: So the victims’ struggle remains very difficult, especially in Africa?

FG: Another lesson from the Habré trial is the key role of the victims, without whose perseverance this trial would not have happened, and the importance of recognizing their rights to truth, justice and reparation. Their struggle continues, as procedures to request reparations should now start. This case also highlights the role over the last 20 years of NGOs supporting the victims, including of course the FIDH and its member organizations in Chad and Senegal. The trial also teaches us that impunity in Africa will not be overcome unless the States, like Senegal, assume their responsibility to hold fair, impartial trials of suspected perpetrators of the most serious crimes, either on their territory or elsewhere in Africa.

JusticeInfo: The name of current Chadian President Idriss Deby Itno, who was army chief of staff at the time, often came up during the Habré trial. Do you think justice has really been done if Deby did not appear before the court?

FG: Current Chadian President Idriss Deby Itno was indeed army chief of staff at the time and his alleged responsibility was evoked notably in the events that happened in Sar and more generally the sequence of repression in 1984 known as “Black September”. As current head of State at the beginning of his fifth mandate, he is not troubled by justice and doesn’t have to explain his alleged responsibility for crimes committed by the Habré regime. Should we have waited until all the protagonists of that black dictatorship could be tried before starting the Habré trial? How much longer would we have had to wait? No doubt too long for the victims, of whom some have already died. Trying Habré was necessary for the victims, for Chad, for Africa and for History. That doesn’t stop us continuing to demand that all those presumed most responsible for international crimes be brought to justice. That is what the FIDH, its member organizations and victims’ associations have never stopped doing.

JusticeInfo: When the start of the Habré trial was announced, N'Djamena quickly organized trials of some suspected Habré acomplices. Was that a way to avoid revelations that might have stained Idriss Déby?

FG: The hasty trial in 2015 of former agents of the DDS (Directorate of Documentation and Security, Habré’s political police), which we had been demanding for 10 years, shows Chad probably did not want to see them testifying before the EAC. These agents would have been in their rightful place alongside Habré as accused persons in Dakar. But would they have besmirched Idriss Deby? It’s possible but it is not certain. Did Chad fear EAC measures of clemency towards them? That is one theory. Our only regret is that the trial before the EAC could not be the trial of all the mechanisms of the Habré regime, as well as Habré himself. But that does not take away from the exemplary way the trial was conducted by the EAC and the historic dimension of this verdict.