The archives of Colombia’s National Centre of Historic Remembrance (CNMH) were put online a month ago. They comprise just over 160,000 documents compiled over four years. They can be freely consulted on the website of the CNMH, which was created by the government in 2010 to shed light on the violence that has wracked this Latin America country for the last 50 years.

Everything is there, or almost: the often harrowing testimonies of victims, reports from labour unions persecuted by the army of the extreme right, the tribunal sentences, the documents of certain guerrilla movements, and 8,000 documents declassified by the CIA and the American Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), given by the National Security Association (NSA), which allow a glimpse into US involvement in the Colombian conflict.

Unlike other data banks on past conflicts like those of Guatemala, El Salvador or Argentina, these virtual archives are unique in giving a voice mainly to those who suffered directly from the political violence. “We have given priority to the information coming from civil society and victims’ organizations,” explains the director of these online archives, Ana Margoth Guerrero.

In order to obtain these archives, her team carried out meticulous research, going to look in all the conflict-affected regions for documents that would enable pieces of the puzzle of these recent decades of war to be put together. “We first had to gain the trust of the associations, even in the middle of continuing the conflict,” says Guerrero. We are an independent body, independent of the State, which these abandoned communities distrust. “In some cases we really had to convince people to bring out the box they were keeping under their bed like treasure. They didn’t give us everything straight away.”

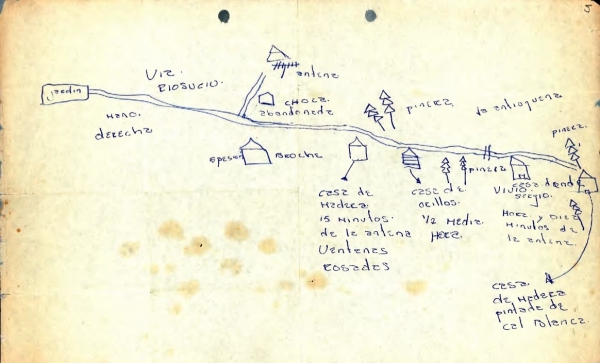

Handwritten manuscript by relative of disappeared person Human Rights Archives in Bogota

The Remembrance Centre representatives first explained what they were doing and taught the associations to organize, classify and digitalize their own archives. Little by little, these organizations understood that their documents would be safe if a copy was preserved by the Centre, and that they would be more useful if they were accessible to everyone. “They realized that if they did not share them, we would never find out the truth,” commented the director.

The result is a loyal and tough picture of the violence in Colombia, with thousands of details: handwritten testimonies, poems, private diaries, photographs and drawings that sometimes made it possible to find the bodies of some of Colombia’s 51,000 disappeared. This very diverse collection also allows us to retrace the resistance of the villagers who kept a tireless record of what the armed factions subjected them to, hoping that one day justice would be done.

Protest march by the Association of Colombian Rural Workers, violently suppressed by the extreme right, Bogota 1972. Human Rights Archives in Bogota

These documents, meant mainly for the victims and the universities, have moreover become a weapon for them. “The prosecution recently consulted some of these documents in the case of a popular leader on the Pacific coast,” explains the director. To avoid the risk of hacking, the Remembrance Centre plans to have a copy of its archives hosted in Switzerland, with the help of Swiss peace institute Swisspeace, as Guatemala has done.

The fact that the originals have not been taken off to the capital means local associations can re-use the testimonies, photographs and records to explain to local schoolchildren and the public in general what happened in their region. “These are not just the archives of terror,” says Ana Margoth Guerrero, “they are also a tool of reparation.”