In Tunisia, a growing movement called Manich Msamah (“I will not forgive”) is using the raw voice of the street to try and topple the President’s bill on “economic reconciliation”. No forgiveness without transparency on economic crimes, say its slogans.

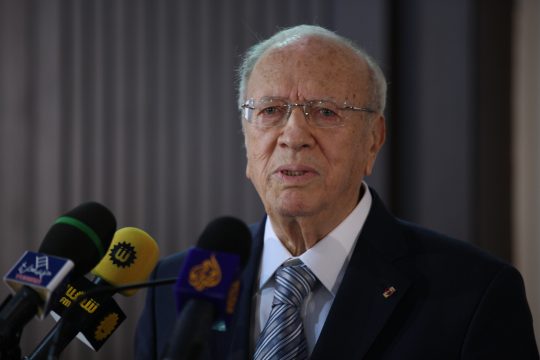

On July 14 2015, in the steamy heat of summer and in the month of Ramadhan, Tunisia’s 89-year-old President Beji Caied Essebssi presented a full cabinet with his Bill on “economic and financial reconciliation”. The Bill proposes two main things. First, an amnesty for senior government officials suspected of misusing public funds, without the truth being revealed or the accounts presented. And second, the closure of pending cases of businessmen close to the inner circle of ex-president Ben Ali, in return for a confidential sum to be paid to the State. All this would be handled behind closed doors by a conciliation commission controlled by the executive powers which would take the place of the Truth and Dignity Commission’s arbitration committee.

But, unlike the opposition parties, young left-wing activists are not swallowing the President’s plan. They say they will defend the values and aspirations of the Tunisian revolution: freedom, equality, dignity, social justice, the right to work and equal sharing of wealth.

Aiming to make the Bill unpopular

They followed closely the President’s declarations on how he wants to “turn the page on the past once and for good” and propose a judicial framework to “pacify the business climate”. Then planned a counter-attack on what they call “the law to whitewash the corrupt”.

A Facebook page was quickly set up bringing together jurists, teachers, students and unemployed people with diplomas, whose average age is 25. This came after a call on August 14 by blogger Azyz Amami, one of the icons of the revolution. “No, I will not forgive,” he said. “This law will not pass. We will set light to the Assembly if necessary!”

His call was immediately adopted as a title for the new page: Manich Msamah (I will not forgive) and to establish the identity of this new movement which has one aim: to campaign against this law on social networks and in public, to make the Bill unpopular. They hope this will topple the President’s initiative, which is now waiting to be debated and approved by Parliament.

Defending the revolution

It all started with virtual friendships between Internet users dating back several years before the revolution. They were mostly high school and other students, and met each other on the street. They represented the spirit of the protest movement that helped unseat Ben Ali in the winter of 2011.

“We met again at the Kasbah sit-ins 1 and 2* during protests by families of the martyrs and the injured of the revolution,” says 25-year-old computer engineer and Manich Msamah spokesman Samah Aouadi, “and in other campaigns such as one that supported young people accused of vandalism during the uprising of winter 2011.”

“We are still inspired by the wind of the revolution,” the young woman continues, “and we defend the memory of December 17, 2010 to January14, 2011, its dreams and its heroes. We are united against impunity and corruption and media normalization of Ben Ali’s bigwigs. We believe that no reconciliation is possible without revelation of the truth and especially presenting the accounts. That is in the group’s ADN. We have not forgotten…”

Communist-leaning banker Ghassen Besbes, 37, who was trained as a lawyer and is one of the group’s leaders, says this Bill is part of the policies of Tunisian governments after the January 14 revolution. Their aim, he thinks, is to “put politics before economic and social issues”. “The result,” he says, “is that the media and especially the world of economics and finance is now dominated by people who collaborated with Ben Ali, who hindered the development of the country these last 30 years. The President’s initiative is a new attempt to widen the circle of the corrupt and the smugglers.”

Sarcasm and caricature

Driven by a taste for politics, but also irreverence and independence with regard to the authorities, the young activists of Manich Msamah work in a dynamic way. Their favourite tools are humour, caricature and sarcasm, used without moderation in their campaigns on social media to explain what is wrong with the bill on economic and financial reconciliation.

“That is what got the interest of the public right away,” says Samar Tlili, a 27-year-old teacher and one of the group’s founders.

Manich Msamah activists’ decisions are taken without a vote, by “approximate consensus”, after long debates that are often impassioned and disorderly. But despite a state of emergency in the country, they quickly agreed to take to the streets in protest against the July 14 draft law. This took place in a lethargic political climate after two sworn enemies, the Nida Tounes secularists of Beji Caied Essebssi and the Islamist Ennahdha movement, came together in a governing coalition.

Ability to get people on the streets

The movement decided on a first rally on August 28, 2015, in front of the main trade union building. There were about 20 people, mostly staunch members of Manich Msamah. Another one on September 3 drew more people but was savagely repressed by the police, who were not going to just stand by in the face of strong slogans against government passivity, nepotism and corruption: “The people don’t want the new Trabelsi **, “No to normalizing corruption”, “No reconciliation without revealing the accounts”, “Catch the thieves and give the youth their freedom”. The young activists’ Facebook page was hugely successful. Small groups of “Manich Msamah” emerged in various places and went to demonstrate in the streets, despite the blows rained on them by police. More than 2,000 people took part in the protest on September 12, 2015, which was joined by several human rights NGOs, representatives of the Civil Coalition against the economic reconciliation Bill and opposition parties.

“We had become a driving force, almost forcing the politicians to take to the street to oppose the presidential initiative, and imposing the agenda of that demonstration,” recalls Moutaâ Amine Al Waer, 27, manager in a community association and one of the group activists.

Mouhab Garoui, executive director of I Watch, an association working on good government and anti-corruption, says the strength of these Tunisian Robin Hoods lies in their “ability to get protesters onto the streets”.

Thanks to their Manich Msamah T-shirts bearing an image of the hammer of justice, they can easily be seen during protests in public places. They have learned the codes and reflexes of the police, with whom they have been playing cat and mouse ever since the revolution. Scattering when necessary and then reconvening surprise gatherings is a tactic that they master well.

“Global reconciliation”

At the end of October 2015, the Venice Commission, a consultative organ of the Council of Europe, issued an interim opinion on the now very controversial Bill. The Commission deemed that this draft law was not in line with the transitional justice framework and its aim to clean up and reform the public institutions. Debate on the Bill was then postponed until further notice. The members of Manich Msamah are divided between those who think its initiators have buried it definitively and those who think it will be brought back in a different form because, as Ghassen Besbes says, “this reconciliation has become a point of principle for BCE (the President), who cannot stomach so much resistance to one of his ideas”.

Indeed, in December 2015, the Bill’s proposed amnesty on currency crimes was slipped into the 2016 Finance Law, but then declared unconstitutional after an appeal by the parliamentary opposition. In April 2016, Nida Tounes and Ennahda announced after a meeting that they planned to draft a new Bill on “global reconciliation”.

Although the new version of the presidential initiative was cloaked in secrecy by members of the parliamentary majority, the young people of Manich Msamah managed to get their hands on it, thanks to their growing network of friends and informers. At the same time, there is also a new cause to fight: normalization through the media of hardline figures of the old regime, including Abdelwahab Abdallah, who was master of propaganda for the dictatorship.

The group is launching a new counter-offensive in the street…

*The Kasbah sit-ins 1 (end of January 2011) and 2 (end of February) are famous for managing to oust Ben Ali ministers from the first post-revolution government and demanding the election of a Constituent Assembly.

**Trabelsi, the name of ex-president Ben Ali’s family-in-law, whose mafia-like activities are infamous.