Children born as a result of wartime sexual violence in northern Uganda and their mothers face continued and compounded violations of their rights and dignity, says the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ). Without urgent redress, they will continue on a path of marginalization, poverty, and further abuse.

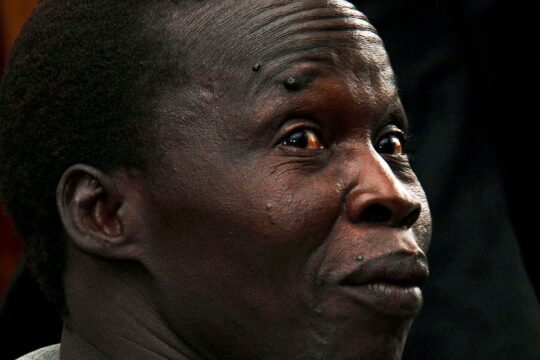

Violent conflict has plagued much of Uganda since its independence in 1962. The most brutal has been the armed conflict between the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), led by Joseph Kony, and the Ugandan Government. The LRA has abducted an estimated 66,000 children and youth to serve as soldiers or sex slaves and targeted girls and women for sexual violence. Government troops are also alleged to have committed serious crimes and human rights violations, including rape.

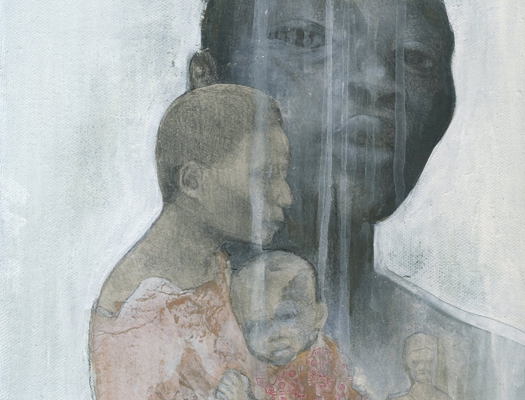

Many girls and women have returned to their communities with children born as a result of rape, sexual slavery, forced marriage, and forced pregnancy — becoming what are known locally as “child mothers” or former “bush wives.”

“The global response to wartime sexual violence has largely focused on criminalizing and punishing perpetrators of rape, but less attention has been paid to what happens to victims back in their communities and to the children they bore as a result of sexual violence,” said Virginie Ladisch, head of ICTJ’s Children and Youth program. “In northern Uganda, these mothers and their children face significant challenges to returning to a dignified life.”

A new ICTJ report, titled, “From Rejection to Redress: Overcoming Legacies of Conflict-Related Sexual Violence in Northern Uganda,” examines the situation facing children born of conflict-related sexual violence and their mothers in Uganda’s Acholi, Lango, Teso, and West Nile sub-regions. It is based on 249 interviews conducted by ICTJ, including with the children themselves, their mothers, fathers, relatives, and neighbors as well as teachers, traditional leaders, religious leaders, and local government officials.

According to the report, because the initial violations against the mothers have gone unaddressed and unacknowledged, there has been a cascade of harms. Stigma and hardship have passed from mother to child, and sometimes even to grandchildren, in an intergenerational cycle of denial of rights and dignity, vulnerability, abuse, and marginalization.

“The challenges that the children born as a result of sexual violence and their mothers continue to face are overwhelming. They call for immediate action to address their plight,” said Michael Otim, ICTJ’s head of office in Uganda.

One grandmother in Soroti shared, “My daughter returned home [with a baby] . . . Because of the baby the clan people rejected me . . . They asked why I had taken over the baby and not allowed it to die.”

Community members often blame the children and their mothers for the violations committed by armed groups against communities. They may call them pejorative names, such as “Kony’s daughter,” “rebel child,” “prostitute,” and “killer.”

One young mother from Lira who spoke with ICTJ explained: “I am a business person, but every time my customers are told that I returned from the bush they stay away from buying my things.”

While limited government programs for conflict victims do exist, there are none that take into account the specific challenges facing children born of conflict-related sexual violence and their mothers. And existing programs are often difficult to access, particularly for children born of sexual violence and their mothers, because of a lack of public awareness, excessive paperwork requirements, and high rates of illiteracy among women.

To seek possible ways forward, ICTJ is convening a high-level symposium in Kampala on October 28-29, 2015, to explore strategies and consider proposals for addressing the rights and needs of children born of conflict-related sexual violence and their mothers within existing government programs and policies. The symposium will provide an opportunity for policy makers and stakeholders to strategize and coordinate their response.

The ICTJ report calls on the Ugandan government to officially acknowledge the harms these victims have suffered and provide targeted redress, such as providing access to land to rejected and ostracized children, opening spaces for dialogue and truth telling in order to clarify how and why violations occurred, and passing the draft National Transitional Justice Policy.

“In order to provide meaningful redress to this vulnerable population and end the cycle of revictimization, the government of Uganda must establish truth and justice for the violations that occurred, and assume responsibility for its part in the initial violations against these mothers that continue to affect them and their children today,” said Ladisch.

The full report may be downloaded here. The briefing paper may be downloaded here.

See a photo gallery of drawings by affected children here.