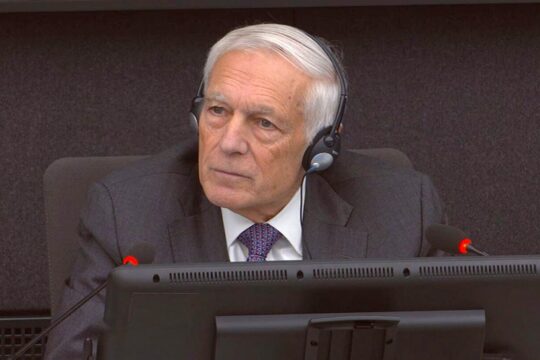

In October, the new Sri Lankan government of President Maithripala Sirisena co-sponsored a UN Human Rights Council Resolution calling for a wide range of transitional justice mechanisms after 26 years of armed conflict with the Tamil Tigers. These include a war crimes court with participation of international judges, prosecutors and lawyers. But the government now seems to be backtracking. At the end of June, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein said he “remains convinced that international participation in the accountability mechanisms would be a necessary guarantee for the independence and impartiality of the process in the eyes of victims”. The Monitoring and Accountability Panel (MAP), a panel of international lawyers nominated by a Tamil diaspora group to independently monitor and advise on transitional justice, agrees. US and UK-educated international lawyer Richard Rogers, Secretary and panel member of MAP, spoke to JusticeInfo.

JusticeInfo: The MAP said recently that Sri Lanka’s progress on transitional justice is “slow and below expectations”. Why do you say this?

Richard Rogers: First, I think it is important to remember the context. This was a brutal and bloody conflict that spanned 26 years, during which massive crimes were committed on both sides, the government and the Tamil Tigers. But the scale was different, and the government committed the vast majority of the crimes. And it’s estimated that between 40,000 and 70,000 people were killed, with the most intensive crimes being committed by the military, in the final weeks of the war in 2009. That has led to allegations of war crimes, crimes against humanity and even genocide. So the crimes are too big to ignore, but also too serious for the Sri Lankan army to accept responsibility, and therein lies the crux of the problem we face today.

In terms of the Sri Lankan government’s progress, I think it’s fair to say that legitimate hopes were raised by the government’s position in 2015 when it spoke about justice and reconciliation and sponsored the Human Rights Council Resolution (…), but since then President Sirisena and the Prime Minister have been backtracking on those commitments and it’s become clear that the coalition government is too weak to follow through on what it promised. It is now said that there will be no international actors playing a significant role in the court. Contrary to the assessment of all international experts, including the UN, the President and Prime Minister now say that the Sri Lankan judiciary are capable of managing the process themselves. So this is worse than slow, this is an intention not to deliver at all and not to fulfil the government’s obligations to victims.

JusticeInfo: And why do you think a war crimes court in Sri Lanka needs international judges and lawyers?

RR: Now in any post-conflict situation, the best solution would be for the accountability process to be dealt with by national courts, but this should only happen if they are willing and able, and if the actors, including the judges and prosecutors, are independent and impartial and have the necessary expertise to manage those types of cases. Unfortunately it is very rare for any national courts to have the capability to do so after a long armed conflict, and Sri Lanka is no exception to this. From all the information that we have (…), it’s obvious to any credible observer that the Sri Lankan courts are not ready for this process, in fact it will probably take decades before they have practitioners who are able to deal with this in a way that meets international standards. I am not saying that there are no good lawyers or judges in Sri Lanka, there are some excellent ones. But technical ability is not the same as independence and impartiality. And we in the MAP believe that the local actors are simply too vulnerable and too partisan to manage a war crimes court by themselves. So neutral international judges and prosecutors with no personal interest in the outcome are needed to ensure legitimacy and victims’ trust.

JusticeInfo: Why do you think the Sri Lankan government has changed its mind on this point?

RR: I think what we have in Sri Lanka is a weak coalition government that’s trying to manage a severely war-torn country, with several factions competing for power including the Rajapaksa faction (Mahinda Rajapaksa is the former hard-line President), and it’s fair to say that any country that has suffered decades of conflict is inherently unstable. It’s clear that in Sri Lanka the military fears that it will be condemned by a hybrid court, because they know they have been accused of most of the mass crimes, and so the coalition government fears a backlash from the military and intelligence services, who still wield a huge amount of power.

JusticeInfo: So has the government made any progress on transitional justice?

RR: Yes. My sense, and I think many people’s sense, is that there are some people in the Sri Lankan government who really want this transitional justice process to work. And we’ve seen land that’s been returned from the clutches of the military who stole it, we’ve seen an Office for Missing Persons that has been set up. It’s fair to say that it has made more progress than any former Sri Lankan government, which is something to be happy about. But we are starting from a very low level. And although it’s good that the current government has shown an intention and some real will to consult civil society, the problem is that it then goes and takes major decisions without taking into account their views. So I think it’s a case of one step forward, half a step back and then trip over. And that’s not really going to bring satisfaction to the victims.

JusticeInfo: What about a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) ? Would you support that?

RR: The problem of partiality and bias that applies to any criminal justice process would apply equally to a TRC. But having said that, if the Sri Lankan government set up a TRC with both credible national actors and international jurists sitting side by side, then that type of process could make a great contribution to the overall transitional justice process, if used in combination with a criminal court.

JusticeInfo: So what do you think should be the government’s priorities now, in terms of transitional justice?

RR: As well as the consultation process, I think the Sri Lankan government simply has to figure out a way to resist domestic pressure from the military or security service and plan for a hybrid court, one that will have international participation and will therefore be credible. If it’s too difficult to do that in Sri Lanka itself, then they should consider situating the court in a third country, and why not? Because if the ultimate prize is long-term stability, then the government should swallow its nationalistic pride and move the court somewhere else, somewhere safer where it can function free from interference. And if that’s too hard to swallow, it should refer the issue to the International Criminal Court in The Hague. Another priority that is parallel with all those issues is a credible and trusted witness protection system, and preparations for that need to start now, with international experts helping. That’s absolutely crucial for any process, whether it’s a domestic court, hybrid court, the International Criminal Court or a Truth and Reconciliation Commission. People that testify and give evidence need to know that they won’t be subject to retribution for doing so.