How should the Syrian war be documented as the number of dead continues to rise? How should the stories of the Bosnian and Chechen conflicts in the 1990s be told? Invited by the WARM festival, journalists, activists and researchers came together in Sarajevo on June 29, to talk about the work they are doing to document recent conflicts, and the specific challenges they are facing.

When the war started in former Yugoslavia in 1991, Suada Kapic thought immediately of documenting it, without knowing that her town, Sarajevo, would soon suffer the worst siege in history: 3 years and 8 months of being surrounded and bombed, leaving 11,000 people dead in the Bosnian capital alone. Suada Kapic and her friends started a unique collection of documents which are available in a few clicks on a website, FAMA, to tell people – students, researchers, interested citizens – the story of the former Yugoslav wars and the siege of Sarajevo of which they were victims.

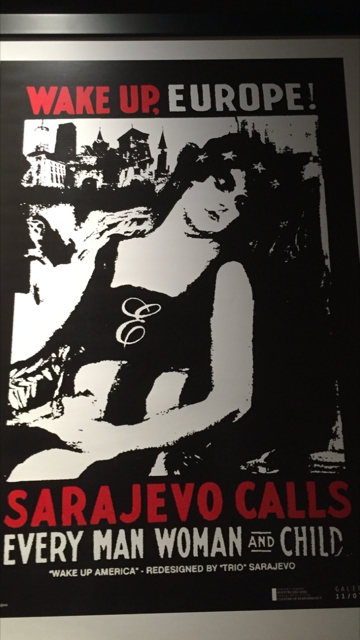

But Suada and her activist friends see now that virtual reality is not enough, including for young people from the republics of former Yugoslavia. Telling the story to a 16-year-old born in Sarajevo ten years after the war needs to be done in a completely different way than in the early 2000s when the war was still fresh in people’s minds. This is all the more so since the traces of the war have gradually disappeared from the Bosnian capital. Almost nothing remains as a reminder of the siege except the tiny “life tunnel”, that made it possible to break the encirclement of the Bosnian Serb forces, and can be visited today. And history books tell things very differently depending on whether they are Serb, Croat or Bosniak. Hence the determination of Suada Kapi and Adnan Pavlovic of the WARM association – which has collected 300 hours of film about the siege – to create an independent museum in Sarajevo. This is a real challenge given the authorities’ lack of interest in a politically and symbolically charged project that they would not control.

Cécile Hennion is working on a project of the WARM association to document the war in Syria. She has come up against a challenge that Suada and Adnan never met in the 1990s: she is swamped by masses of documents. Whereas Suada and Adnan spent hours trying to find bits of film, convince people to lend their photos to be digitalized, or restoring precious images of the former Yugoslav wars, technology has radically changed and democratized archiving work. To film, mobile phones have replaced the camera, YouTube has replaced television as a broadcaster, Skype has replaced the telephone and the prices of archiving software have tumbled. Whereas in the past it was difficult to find images, now there are too many. In addition, there is the challenge of verifying sources, which is more crucial than ever today because, as Cécile Hennion stresses, everyone is now filming, including fighters, human rights activists and journalists.

Formidable work done

There is another difficulty: contrary to popular belief, a lot of online material disappears. Two million videos of the Syrian conflict have already been removed from the Internet. And there is another obstacle, geopolitical this time, of how to talk about the ongoing conflict. Should we refer to archives of the “Syrian conflict” when Syria could break up and the Iraqi border is disappearing under the impact of Daech?

Archivist Zsusanna Zadori was asked to help build archives on the two wars in Chechenya in 1994-1996 and 1999-2000. A website www.chechenarchive.org was launched a month ago. In total, 500 videos and 1,270 sequences have been carefully organized, identifying precisely 745 victims of abuses by the Russian forces and their local allies, backed up by evidence and testimonies. These videos have been put together by a handful of journalists and activists, with the aim of one day documenting the war crimes committed against the Chechen people for an international tribunal. These archives are stored physically in the Swiss capital Bern, to avoid any risk of them being destroyed by “interested parties”. Zsusanna Zadori does not, however, have illusions about the chances of an International Court one day using these archives. “Given Russia’s political power, it is difficult to imagine the perpetrators of these crimes being prosecuted in a criminal court,” she says. “But at least they have now been documented in a database that can be accessed by the media and anyone interested.” The database is divided into two parts. One part is confidential, so that witnesses’ lives not be put at risk if their identities are known, and one part is public.

Whether it be the archives of the Chechen wars in the 1990s or the former Yugoslav wars, formidable information gathering, documentation and educational work has been done. It remains to be seen to what extent it will bear fruit for new generations and vaccinate them against the horrors of war.