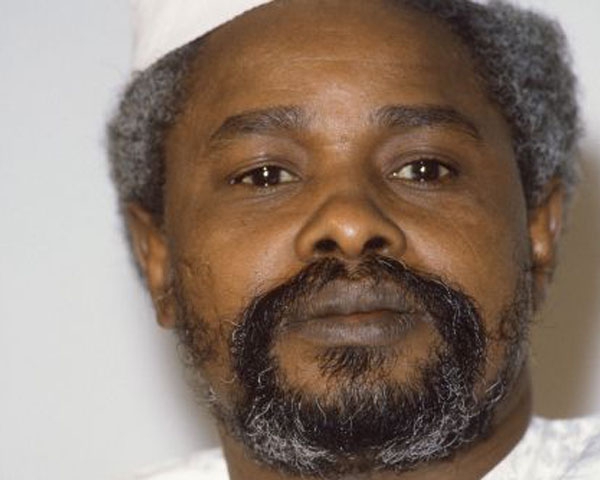

Justice must not only be done, but also be seen to be done. This saying has never had greater resonance as in the development of international justice. How can a historic trial serve as an example if the victims and communities most directly concerned are not aware of what is going on? This, however, is what is now happening with the trial of former Chadian dictator Hissène Habré before the Extraordinary African Chambers (EAC) in Senegal. An awareness campaign in Chad has come to a halt, even before the trial ends and a judgment is handed down on Habré.

On Monday, Clément Abaïfouta testified in the Hissène Habré trial. Abaïfouta, a student at the time, was jailed in the sinister prisons of the former dictator, who is accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity for the deaths under his rule (1982 to 1990) of 40,000 Chadians. During his years of detention, Clément Abaïfouta was used as a grave digger. He was also a witness to numerous acts of rape and torture by the DDS political police, whose very mention sends shivers of fear down people’s backs. That was the focus of his testimony before the Extraordinary African Chambers in Dakar. His memories of that time continue to haunt him. After testifying in the morning only metres away from the fallen dictator, he shared his emotions with JusticeInfo.Net. “As I was testifying, I looked Hissène Habré straight in the eyes,” he said. “I was moved to be there, but I also felt anger rising in me against this man who caused so much suffering to so many people.”

But most people in Chad, who do not have television, will not hear Clément Abaïfouta’s testimony. The court’s awareness campaign stopped on October 19, although coverage of an ex-Head of State’s trial has rarely been so crucial. Chad, where the survivors and victims’ families are based, is more than 4,000 kilometres from the court in Dakar. Nearly 80% of Chad’s population is illiterate. They are not going to get their news and information from the EAC website in a country where Internet access is reserved for a tiny minority. The awareness campaign had enabled Chadian journalists to cover the trial in Dakar and broadcast programmes on community radios, which have a high audience in Chad. Outside the capital N’Djamena, public screenings of trial extracts had been organized in several towns in several languages. “It is sad,” says Reed Brody of Human Rights Watch, who has for 15 years been part of the campaign to bring Hissène Habré to justice. “The awareness campaign managed to reach marginalized populations far from the urban centres who were victims of Hissène Habré.”

So why has this campaign been stopped since October 19? The answer is bureaucratically simple: the trial has been extended beyond the time initially planned. Its 8.5 million Euro budget, of which 10% was reserved for communication, was drawn up by the main donors (Chad, the European Union and the African Union) for the initially planned period. So now, will the donors make an additional effort to ensure that this first trial organized under the auspices of the African Union is covered throughout for the victims and Chadian population, and that this first trial of an African dictator on African soil resonates throughout Africa?