Since September 11, 2001, the strategy of targeted killings has become more and more widespread internationally, in the name of the War on Terror. But the question of their legality is controversial. The widening of targets is turning this tactic into a specific way of waging war.

Almost immediately after Al Qaeda attacked American soil on September 11, 2001, the United States promised it would hit its enemies wherever they were in the name of the “war” on terror. Paris did the same thing in Mali in 2013, still as part of the fight against armed Jihadists. Then, after the November 23, 2015 attacks in Paris and Saint Denis, France drew up its own list of “high value targets”, as investigative journalist Vincent Nouzille reveals in his new book Erreurs fatales (“Fatal Errors”). The journalist claims that between 2013 and 2016, some 40 targets abroad were executed by the French army and special forces, but also by the US army using information supplied by France. “France is applying the law of vengeance,” writes Nouzille. “This `licence to kill` sometimes looks like cold revenge and extrajudicial executions.”

Legal or illegal?

International law does not ban targeted attacks, but defines a precise framework. Their legality can only be determined on a case by case basis. First, it is forbidden to attack on foreign soil without the authorization of the State concerned, except in the case of an imminent threat. In early December 2016, Mohamed Zouari, a Tunisian engineer specialized in drones, was killed in front of his home in Sfax. This killing, which was attributed by the Palestinian Hamas movement to Israeli secret services and by Tunis to a foreign force, provoked outrage in Tunisian society with claims that national sovereignty had been violated. The tactic of targeted assassinations was used in the early 2000s by Israel, notably in the West Bank and Gaza. But France’s targeted killings in Mali and Iraq – carried out after requests for intervention from these countries – are not considered illegal, provided they respected certain conditions. In the case of an armed conflict, they must target combatants, or, if it is civilians they must be directly involved in the hostilities. Such killings are also required to be proportional, and steps must be taken to minimize harm to civilians. There has so far been no investigation into whether these conditions were met. The case of Syria is even more controversial. Acting without a UN mandate and without authorization from Damascus, France has eliminated French Jihadists fighting for Islamic State in Syria, saying it is “legitimate defence” allowed under the United Nations Charter. But in international law, targeted execution is only legal if it is necessary to protect human lives. It cannot be an act of revenge or punishment. The aim must be to protect lives, not inflict death. In Syria, France should have demonstrated that an attack was “under way” or “imminent” and that there was no other way to avert the threat. It has not done this.

Pre-emptive killings

These lists of people to be killed are drawn up, submitted for approval to the President and head of the army, even as terrorist cases are before the French courts. “At the Elysée palace, François Hollande is clearly approving `confidential` military operations aimed at eliminating terrorist leaders, without bothering with the cumbersome paths of justice,” writes Vincent Nouzille. “Whether it is in the Sahel or now in Syria or Libya, he has committed to the path of war, putting justice in second place.” Nouzille’s book casts a bigger light on the French Head of State’s declarations to journalists Gérard Davet and Fabrice Lhomme, narrated in Un président ne devrait pas dire ça... (A President should not say that”, in which François Hollande said he had given a green light to at least four executions. Vincent Nouzille sees this as a de facto re-establishment of the death penalty, whereas cases are open before French courts and victims are waiting for justice. “Judicial procedures that are under way are being short-circuited in favour of taking justice into one’s own hands,” says lawyer Patrick Baudoin, executive president of the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH). He criticizes “arbitrary decisions which are not subject to control” and of which “the President of the Republic has personally boasted”. Baudoin thinks that “Parliament should be allowed to look into what has been done. In the absence of information and oversight, we have entered a domain outside the rule of law, and that is inadmissible”.

The series of attacks carried out in France nevertheless make such dissenting voices “scarce, or hardly audible”, the lawyer adds. Baudoin’s stance is nevertheless nuanced. He adds that some operations can be “useful”, but regrets that nobody has brought “proof of imminent danger”, as required by international law. In France, political protests, including within the government, have not focussed on the practices but rather on the fact that the Head of State was able to express himself publicly on issues viewed as national defence secrets. Speaking of the substance, Jean-Luc Mélenchon, leader of the Left Front, nevertheless expressed the view that “in principle, these types of actions fall under the jurisdiction of an international criminal tribunal”. France has ratified the Statute of the International Criminal Court, which would thus have a mandate to prosecute extrajudicial executions if considered as such. “Yes, it would have a mandate if French officials were involved,” explains Patrick Baudoin, “even if, in general, it takes up cases of mass crimes.” According to Vincent Nouzille, “there are currently operations being carried out by France, on the express orders of François Hollande, to neutralise a certain number of French Jihadists who went to Syria and who are now said to be back in France. Some 500 French citizens are still in Syria and, with Islamic State suffering defeats on the ground and calling for attacks on European soil, the French services are worried about them coming back.

Extending the field of war

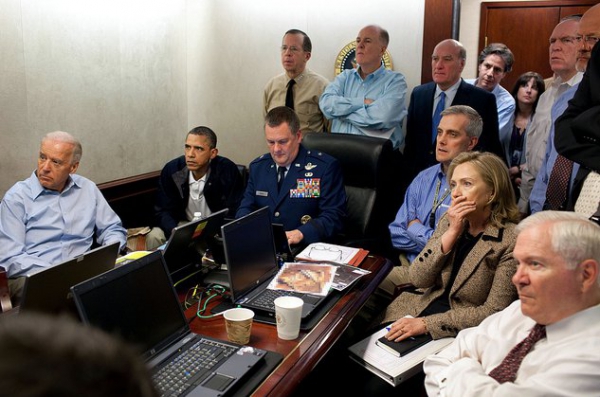

The list of people to be eliminated has been considerably lengthened in the name of the war on terror and legitimate defence. The US has intervened without a UN mandate in Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen, particularly through its special forces or drones, which have become the ultimate weapon against targets. The most high profile assassination remains that of Osama Bin Laden in Pakistan by the CIA and special forces on May 2, 2011. The aim of the operation was to inflict death, which is forbidden by international law. According to the New York Times, the CIA adopted the tactic of targeted killings after the revelations about its secret prisons in Europe and Africa, where terrorist suspects were tortured by security services. According to the newspaper, the revelations “paved the way for the CIA to change its focus from capturing terrorists to killing them, and helped transform an agency that began as a Cold War espionage service into a paramilitary organization”. This new form of war, started by George W. Bush, has been theorized by Barack Obama. In May 2013, President Obama spoke openly about targeted killings on foreign soil and a legal framework, some of whose terms remain sufficiently vague and subjective to give a good margin for manoeuver to the armed forces and security services. Human Rights Watch Executive Kenneth Roth thinks that drones can reduce the danger of civilian victims in places where the US is in armed conflict, like Afghanistan, Iraq and Syria – because they are “exceptionally precise” and “few civilians are in the proximity”. But, he says, in places where the US is not officially at war like Somalia and Yemen, even if Obama’s 2013 speech set a framework, “because drone strikes are shrouded in secrecy, it has not been possible to determine whether his administration is applying it. By all appearances, the administration seems to have frequently defined an `imminent` lethal threat so broadly as to effectively revert to the more lax standards of war”.

Victory for terrorism?

In summer 2016, the Obama administration published for the first time a review – deemed well below unofficial figures – of military operations conducted outside US war zones in the last seven years. According to this report, the US launched 473 operations, resulting in the deaths of some 2,500 combatants and 64 to 116 civilians. The Council of Europe expressed its concern in a 2015 report. “To justify the wider use of targeted killings, some States have stretched the concept of non-international armed conflict in such a way that it includes numerous parts of the world as ‘combat zones’ in the international war against terrorism’,” the Council said, adding that “this strategy risks clouding the lines between armed conflict and the fight against criminality, to the detriment of human rights protection”. UN Special Rapporteur on Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights Ben Emmerson noted in 2015 that targeted attacks by drones were against human dignity and forced people in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia to change the habits of their society, such as coming together for funerals or social gatherings. As more and more countries equip themselves with combat drones, the lack of transparency inhibits independent control of these strikes, which could determine whether or not they are legal and deliver justice to collateral victims. In France, the state of emergency was renewed, along with laws allowing mass surveillance and targeted assassinations. “Thus we are gradually sliding into a state where all democratic rules are ignored,” says Patrick Baudoin, “and proving right the Jihadists who said that our democracies, which are supposed to respect human lives, are just a façade.” By these acts, we risk encouraging more people to join the Jihad, he concludes.