The timing may be just a coincidence. But the coincidence this week of a former Guatemalan minister’s trial in Spain for summary executions of eight gang leaders and questions on the legality of French and American targeted killings of alleged Islamic State terrorists raises a real issue. How can you defend people who are indefensible in the name of a justice system that they neither respect nor practise? The question is as old as democracy itself, and has always been on the minds of the lawyers who defend “public enemies”.

The trial in Spain of Carlos Roberto Vielmann, 60, a former Interior Minister of Guatemala from the country’s élite, is exemplary. Vielmann thought he could escape the judicial authorities in his country by going to Spain, where he also obtained citizenship. But Spanish justice has now caught up with him. He could face a sentence of 160 years’ imprisonment (20 for each assassination) and payment of 300,000 Euros compensation to victims’ relatives for ordering an attack on a prison to mask the execution of eight gang leaders who were in there. Vielmann denies the allegations, and was even seen as a “moderate” in the ultra-violent political world of Guatemala at the time. But as JusticeInfo correspondent in Madrid François Musseau writes: “This trial in Spain could be somewhat misleading. One might at first think it stems from the well-known zeal of Spanish magistrates acting on the principle of “universal jurisdiction”. One could hardly forget the spectacular arrests ordered by magistrates such as Baltasar Garzon, like that of Pinochet in London, or the extraditions to Spain of former torturers in the Argentine dictatorship like Scilingo or Cavallo. However, after the socialist Zapatero came to power in 2009, and then the conservative Rajoy in 2014, Spanish governments have in recent years legislated to restrict sharply these prerogatives – mainly to avoid diplomatic conflicts with China, Israel and the United States.”

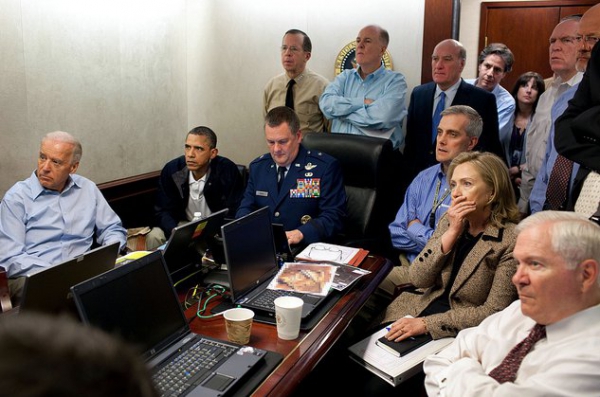

The question of whether extra-judicial executions can be legal arises, albeit in different terms, for members of Islamic State and other terrorist groups killed by the US, France or Israel in places like Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Tunisia and Afghanistan. “International law does not ban targeted attacks, but defines a precise framework,” explains Stéphanie Maupas, JusticeInfo’s correspondent in The Hague. “Their legality can only be determined on a case by case basis. First, it is forbidden to attack on foreign soil without the authorization of the State concerned, except in the case of an imminent threat. Secondly, targeted execution by a State is only legal if it is necessary to protect human lives. It cannot be an act of revenge or punishment.”

This legal framework is often disregarded, according to human rights defender Patrick Baudoin, who criticizes “arbitrary decisions which are not subject to control”. “Judicial procedures that are under way are being short-circuited in favour of taking justice into one’s own hands,” he says. “Thus we are gradually sliding into a state where all democratic rules are ignored, and proving right the Jihadists who said that our democracies, which are supposed to respect human lives, are just a façade.” By these acts, we risk encouraging more people to join the Jihad, he concludes.

Another flouting of the law is the arrest of UN judge Aydin Sefa Akay by the Turkish regime. The judge is appointed to the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), the UN body charged with handling residual matters of the ad hoc tribunals for former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and has diplomatic immunity. But the Turkish authorities ignored a summons to The Hague on January 17 to explain his arrest, and the judge remains in jail. This arrest by Turkey undermines the independence of international justice.

Also noteworthy is the portrait on JusticeInfo of Haythem El Mekki, one of the most influential bloggers of the Tunisian revolution who is now a satirical journalist for private radio station Radio Mosaïque. “His portrait reflects the portrait of a community,” writes JusticeInfo’s Tunisia correspondent Olfa Belhassine. “El Mekki believes he has preserved his independence in the face of pressure groups and his freedom of expression. He is followed by a wide and surprisingly diverse audience. El Mekki is one of the most influential opinion leaders in transitional Tunisia, where points of reference are often lacking. Nearly 500,000 people also follow him on Twitter.”