Universal jurisdiction is making slow but steady progress as a tool against impunity, and not only in Europe. This is according to a report published on Monday March 27 by five human rights organizations.

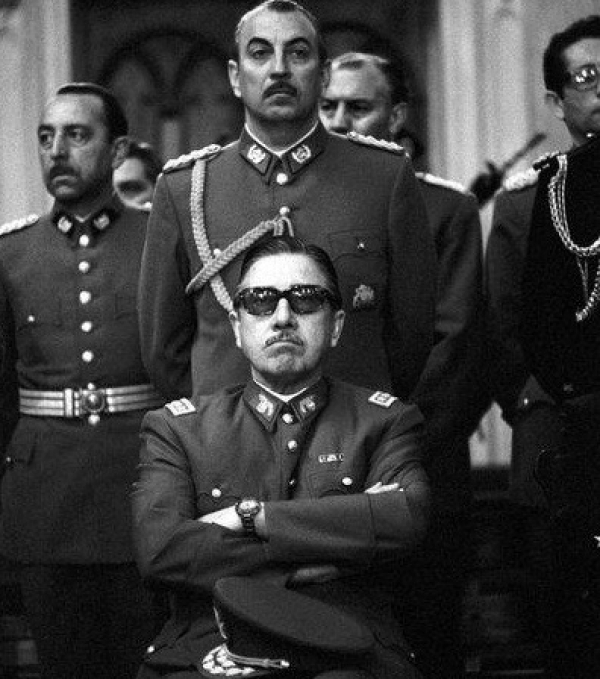

Forty-seven people suspected of crimes committed in another country were tried before national courts in 2016, according to the report, entitled Make Way for Justice. This marks slow but steady progress for the principle of universal jurisdiction, which is being used more widely, including outside the European Union. “Despite constant attacks, universal jurisdiction continues to be a significant tool in the fight against impunity,” says Philip Grant, director of the Swiss NGO TRIAL International. “For victims, it is often the only way to justice.” The first universal jurisdiction case was the high-profile one of former Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, who was hospitalized and then arrested in London in October 1998 and wanted by Spain for crimes committed in Chili. After many political and legal twists and turns, the former dictator finally managed to return to his country without being put on trial. But since then, numerous countries have adapted their legislation so they can try war crimes suspects of any nationality in their own courts. The report, published by TRIAL International in collaboration with International Foundation Baltasar Garzón (FIBGAR), the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and REDRESS, shows that universal jurisdiction remains the fall-back mechanism to try perpetrators of international crimes (war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide).

European judicial authorities target Syrian crimes

Syria is the most flagrant example. Since the beginning of the war, thousands of pieces of evidence have been gathered to document crimes. But given that all attempts to refer Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC) have been blocked by Russian and Chinese vetoes in the UN Security Council and the impossibility of setting up a special court, NGOs in particular are looking at the possibilities offered by universal jurisdiction. The mass arrival of Syrian refugees on European soil has considerably widened the possibilities, especially in Europe where universal jurisdiction is closely linked to immigration policy. The European Union refuses to become a “safe haven” for war criminals. In 2016, Austria, Finland, France, Germany and Sweden launched prosecutions for crimes committed in Syria, and investigations are under way in Switzerland, Norway and the Netherlands. During the year, three people were convicted for war crimes. “While 11 Syrian suspects were arrested or prosecuted in 2016, all of them were low-to mid-level perpetrators,” says Philip Grant of TRIAL. “High-ranking suspects predominantly remain protected by powerful political allies.” France opened a case in September 2015 at the request of the Foreign Ministry, on the basis of the Caesar report, which documents torture and murder carried out in the jails of the Syrian regime. In October 2016, the Paris prosecutor’s office also opened an investigation at the request of the Finance Ministry into the LafargeHolcim company, for allegedly having put its staff deliberately in danger, bought oil illegally from Jihadists of Islamic State (IS) and for funding a terrorist group. In November, Sherpa, the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights and 11 ex-employees of the company also filed a complaint against Lafarge Ciment Syrie.

The Mechanism for Syria

In December 2016, the UN General Assembly approved the setting up of an International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism to centralize evidence gathered throughout the war and prepare cases for future prosecution. The Mechanism, which has been slammed by Syria and Russia but has wide support among Gulf countries led by Qatar, is to be funded at least initially by voluntary contributions. The UN is currently trying to identify the future head of the Mechanism, whose offices will be based in Geneva, near to the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria, which has since 2011 been documenting crimes committed by the regime, the rebels, the Jihadist groups and international forces. Files could in future be sent to the ICC if it is given jurisdiction, or to any future special court should it become a reality, or to national judicial authorities that can exercise universal jurisdiction.

The expansion of universal jurisdiction

The TRIAL report also shows the slow but gradual expansion of universal jurisdiction. The Hissène Habré case has made Senegal champion of the fight against impunity on the African continent. Former Chadian dictator Habré was sentenced to life imprisonment and ordered to pay 30,000 Euros to each of his victims. His lawyers have appealed, and a final decision is expected at the end of April. It has nevertheless taken 20 years to get this result. Dakar only agreed to try the former Chadian President after a long standoff with Belgium, which issued an arrest warrant for him, and after the African Union gave a green light to organize a trial in the name of Africa. In Latin America, Argentina is gradually trying to force Spain to accept the crimes of the Franco regime. In April 2010, Spanish and Argentine human rights groups filed a complaint before an Argentine judge for Spanish victims of the dictatorship. Spain has always refused to implement extradition requests filed against some 20 suspects for crimes against humanity and torture committed between July 1936 and June 1977. But in 2016, Spanish judicial authorities accepted a rogatory commission of Judge Servini de Cubria, and authorized exhumation of the remains of one of the dictatorship’s victims, whose daughter is among the complainants.