A national workshop in Conakry of government and civil society representatives has approved a Bill to set up a Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission in Guinea. This is in line with recommendations from the Interim National Reconciliation Commission (CPRN) after five years of wide consultations.

“The Commission will not have the power to try or to amnesty anyone, since trials are the responsibility of the courts,” said Prime Minister Mamadi Youla at the workshop opening in Conakry on April 12. But he assured participants that the Commission would be politically independent and respect the principles of fighting impunity in light of the country’s realities.

Working over three days, participants from the public sector and civil society drew up the Bill, which will be submitted to the Cabinet before being put to Parliament for approval. Everyone is aware how important this process is. “Guinea needs to reconcile with its past,” said the Minister of Higher Education and Scientific Research at the closure of the workshop. “Our young people ask questions about our recent past which often go unanswered and which require of us all a lasting commitment to truth, justice, reparations and guarantees of non-repetition.”

The Commission’s mandate is expected to cover half a century. Guinea has seen grave human rights abuses under all regimes since independence, including that of current President Alpha Condé, with crimes left unpunished despite protests by Guineans themselves, by the international community and by many national and international NGOs.

Death camp

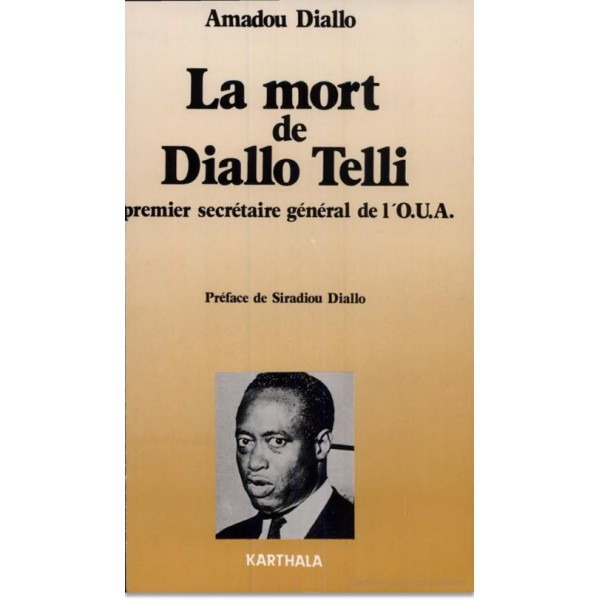

Some of these abuses will stay carved in the collective memory of Guineans for a long time: repression of the Peul ethnic group under President Sékou Touré (1958 – 1985) on conspiracy allegations which were mostly made up to justify imprisonment, torture and summary executions. The Association representing families of victims of the notorious Camp Boiro internment camp works to ensure these crimes are not forgotten and do not go unpunished. Human rights organizations estimate that some 50,000 people died in Camp Boiro, including former Organization of African Unity Secretary Diallo Telli on March 1, 1977.

The regime of General Lansana Conté which followed was marked in its first years by repression against the Mandinka people, ethnic group of Diarra Traoré who led a failed coup attempt in July 1985. He was subsequently executed, but was not the only one to pay since vengeance was wrought blindly on members of his ethnic group. Soussous (ethnic group of the president) and Peuls filled the streets of Conakry to support the loyalist troops but also loot and ransack properties of the Mandinka minority. The exact toll from this painful episode is still not known, but victims are still calling for rehabilitation and reparation.

More recently, on September 28, 2009, soldiers burst into an opposition meeting in Conakry Stadium, firing into the crowd, beating and raping. More than 150 people died and 200 women were raped. This event returned to the headlines after the arrest in Dakar last December 16 of Toumba Diakhité, a close aide of the president at the time Dadis Camara. Diakhité, who had been on the run for seven years, was extradited to Conakry, and Guinean authorities have promised a trial before the end of the year.

Scepticism

Even the current regime could come under scrutiny from the Commission. Numerous opposition demonstrations have been put down violently by the security forces, such as a demonstration on February 20, 2017, in Conakry, calling for schools to reopen after a teachers’ strike. Five people were killed, according to the official figure. There have also been other crimes and unexplained disappearances which have remained unpunished, since there has never been a conclusion to investigations promised by the authorities.

The task that the Commission and its members face is therefore enormous. It will have to document all the cases over the last 50 years, gather testimonies from witnesses and victims whilst ensuring their security, gather material evidence wherever possible, analyse the facts and designate responsibilities, without trying to be a court. There is “no future without forgiveness”, said South African Nobel Peace Prize winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who chaired his country’s Truth Commission after the end of apartheid.

A first challenge for the future Guinean commission will be to convince people of its capacity to complete its work. Many Guineans are sceptical, fearing that the commission will be subject to interference once it starts working, or will simply never get off the ground. Speaking at the Conakry workshop that drafted the Bill, the Higher Education Minister sought to be reassuring. “It is time that Guineans talk to each other and tell each other some truths, but also forgive together in order to move forward,” he said.