Whenever there are serious and /or massive human rights violations within a community or a State, victims, their family members and eye witnesses tend to seek justice and truth about what happened to their loved ones. To ensure that that the truth is uncovered and justice takes its course in the form of prosecuting the perpetrators and offering restitution/compensation to the victims and their families, some societies have also moved a step further by introducing different remembrance projects aimed at honoring the victims, thus reminding citizens of the atrocities that happened in the past so they should not be repeated ever again.

In the past decades, the state of Germany together with its citizens have manifested a mastery in the art of dealing with the violations-atrocities that occurred during the Nazi and GDR era by encouraging social tolerance and promoting related discourse at different levels, fora and platforms . On this premise, I arrived in Berlin with the hunger and eagerness to broaden my knowledge on truth, justice and remembrance from the German perspective.

I was really fascinated at the huge number of different remembrance projects from memorial sites to museums (exhibitions), statutes, signposts and plaques, street names existing across the country, as well as the instructive stumbling stones laid on the streets of several cities in Germany and other European countries[1].

Before the Berlin seminar, I had always thought that the victims of the Holocaust were mostly Jews. Little did I know that Roma (Gypsies), people living with mental and physical disabilities, political opponents, homosexuals, drug addicts, religious groups such as Jehovah's Witnesses, prostitutes and individuals considered to be anti-social were also persecuted and killed by the Nazis. During the two week session, I was confronted with strong emotions and compassion for the different victims, especially after visiting the former Nazi concentration camp at Sachsenhausen.[2] I was particularly struck by the writings of Andrzej Szczypiorski[3], a survivor, on one of the walls within the premises, which reads:

“ and I know one thing more – that the Europe of the future cannot exist without commemorating all those, regardless of their nationality , who were killed at that time with complete contempt and hate , who were tortured to death , starved , gassed, incinerated and hanged …“ [4]

I was equally moved during the tour at the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial[5] that was once used by the STASI as a maximum security prison to detain political opponents of the then communist regime in East Germany. Listening to the stories recounted by the tour guide, who happened to be an ex-detainee of the prison[6], also took its toll on me, especially after realizing how the regime had invested resources in order to permit the employees of the prison to carry out academic research on how to make people denounce each other and/or make individual confessions.[7]

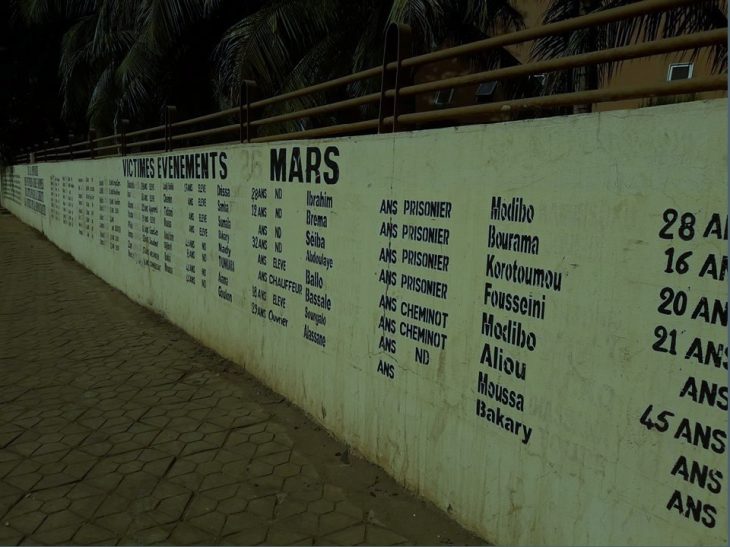

Meanwhile in Mali, where I currently live and work, and Cameroon my country of origin, very little has been done or achieved within the framework of remembrance projects. Looking at the case of Mali, a monument and wall bearing the names of victims was erected at a spot in Bamako now known as La Place des Martyrs [8] in honor of the different individuals that were killed by the military during the fighting that led to the collapse of the oppressive regime of General Moussa Traore on 26 March 1991[9]. The monument or its equivalence has been replicated in the capital cities of other regions in the country. It should be noted that the 26 of March has since been observed as a public holiday in Mali. Additionally, another monument called the monument de la paix [10] was erected in Timbuktu on 27 March 1996 to commemorate the return of peace in northern Mali as well as honor the victims of the 1990-92 rebellion.[11]

Unlike Cameroon, there are no existing projects related to the remembrance of victims of serious human rights violations. This can be attributed to the fact that the country has never witnessed a civil war or a rebellion leading to a change of regime ever since its independence in 1960.

[1] Silvija Kavčič, “coordination office Stolpersteine Berlin” in Stumbling Stones in Berlin: 12 neighborhood walks”, 2nd Ed. Editorial staff (Berlin, Aktives Museum Faschismus und Widerstand in Berlin e.V. Koordinierungsstelle Stolpersteine Berlin Kulturprojekte Berlin GmbH, 2016), 12.

[2] See info on Sachsenhausen Memorial ,http://www.stiftung-bg.de/foerderverein/fuehrungen/en/, accessed April 13, 2017

[3]See info on Andrzej Szczpiorski, http://www.porta-polonica.de/en-sysgb/Atlas-of-remembrance-places/andrzej-szczypiorski, accessed April 12, 2017

[4] See photo 1 in the Annex

[5]See info on Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial, http://www.visitberlin.de/en/spot/gedenkstaette-berlin-hohenschoenhausen, accessed April 12, 2017

[6] Sven Felix Kellerhoff, Learning from history: A handbook for examining dictatorships, 1st Ed. (Berlin, Gedenkstätte Berlin-Hohenschönhausen, 2013), 9.

[7] Peter Erler and Hubertus Knabe, The Prohibited District: The Stasi Restricted Area Berlin-Hohenschönhausen (Berlin: Jaron Verlag GmbH, 2008) 16.

[8] See Photo 2a and 2b in the annexes

[9] http://news.abamako.com/h/42481.html

[10] See photo 3 in the annexes

[11] Ibrahim Siratigui Diarra, La “flamme de la paix” du Mali 10 ans après : Bilan de la réinsertion des anciens rebelles in DDR Désarmer, Démobiliser et Réintégrer : Défis humain, enjeux globaux (Canada, Les presses de l’Université Laval, 2006), 172.

Berlin Seminar: Truth, Justice and Remembrance

JusticeInfo is publishing articles and testimonies from the participants to the Berlin Seminar of the Robert Bosch Stiftung, a partner of our website.

All over the world, societies suffer from traumatic experiences in wars and conflicts. The Berlin Seminar of the Robert Bosch Stiftung brings peace actors from (post-) conflict societies to Germany’s capital to work towards an appropriate approach to addressing violence in their countries. The participants discuss with experts and visit sites of memory. Furthermore, they peer-consult each other and exchange best practices to strengthen their abilities for conflict transformation. The belief is that lasting peace is only possible if the legacy of conflicts is dealt with in an inclusive and constructive manner.

Find more information here