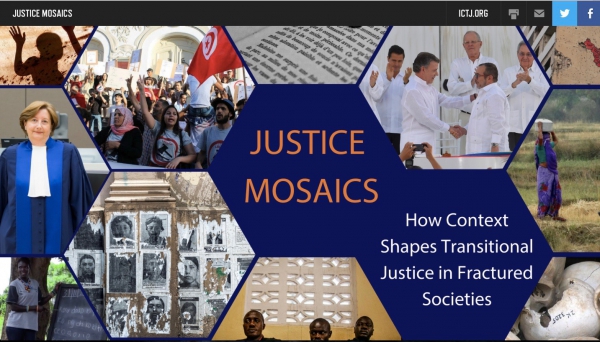

“Justice Mosaics” is the almost poetic title of a welcome new book on transitional justice by the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), an American NGO that is specialist in the field.

This 400-page book, which can be downloaded for free, is subtitled “How context shapes transitional justice in fractured societies”. The idea behind the work, co-edited by ICTJ Research Director Roger Duthie and Vice-President Paul Seils, is to show how transitional justice needs to adapt to local contexts. “We often say that transitional justice is an art, not a science,” say the editors. “Part of the art is in understanding the context, including the opposition to justice, weighing the pursuit of dignity and rule of law against the threats of those who would deny it, and adopting the best strategies to pursue justice and reform in those circumstances.”

ICTJ works passionately in favour of transitional justice, but after 15 years of experience in numerous countries, it is also aware of the limits and obstacles. In the book, the editors argue against any uniform vision of reconciliation processes and transitional justice. “However,” they write, “over the years the field of transitional justice has sometimes seemed to offer formulaic responses to vastly different contexts, which have been taken together as a universal “toolkit” or prescription to be applied wherever massive human rights had occurred.”

They take the example of several countries whose situations are quite different. “What might transitional justice look like in Syria, where millions of people are displaced and a political transition to end the conflict is difficult to envision?” they ask. “Or in Mexico – a complex case that does not conform to traditional ideas of “transition” but where violence that may include crimes against humanity is seen through a framework of organized crime rather than armed conflict, and the rule of law can be said to be severely damaged if not collapsed in many regions? Or in Sri Lanka, where many of those responsible for crimes committed during the civil war are still in positions of government? Or in South Sudan or the Central African Republic, where weak institutions, poverty, and ongoing violence makes for extreme fragility?”

Given this mosaic, it is logical that ICTJ advocates a tailored approach. “In short,” say Duthie and Seils, “we need customized solutions guided by principles, not templates applied without thought.”

One chapter of the book also looks at local approaches to transitional justice, showing both the advantages and limits of local processes.

In other words, transitional justice is not a universally applicable formula, nor a total holistic solution, as its most zealous promoters might have it.

.

.