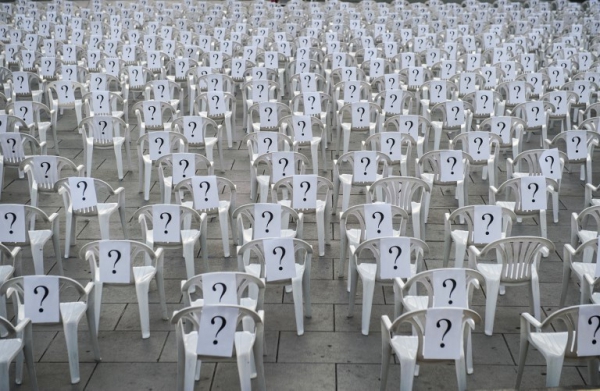

In contexts of political violence, one of the worst forms of psychological torture is not to know what happened to loved ones. And it gets worse with time. Has that person been taken by the army or an armed group? Have they been assassinated? Will they ever be found alive, or at least their remains, if victim of an extrajudicial killing?

“For the past 18 years, every day that goes by is agony for us,” wrote the families of Serb and Kosovar disappeared people in a joint appeal on June 21. Under pressure from them, a UN roundtable was held in Geneva last Thursday and Friday with all the parties, to try to clarify the fate of 1,658 people who disappeared in Kosovo between 1998 and 2000 in a context of political violence before, during and after the NATO armed intervention. Apart from the suffering of the families, the issue of forced disappearances is undermining regional stability, as stressed by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein at the start of the roundtable. He stressed the lack of information about the disappeared was feeding the idea of “collective guilt of one community” and hampering a return to peace and reconciliation “for generations”.

One of the main aims of this meeting (editor’s note: the author of this article helped to organize the conference, as a UN consultant) was to try to resolve in the best way possible the classic tension between the need to access information to find the person alive or dead, and the right to justice, to punish human right violations. All too often in practice, the rare witnesses remain silent because they know their lives and those of their families would be threatened by the perpetrators of the crimes if they revealed information. As for the perpetrators, they also keep the information obstinately to themselves, for fear of spending their lives behind bars. How can this obstacle be overcome and information obtained, which is all the more important as a new tribunal, the Specialist Chambers for Kosovo, begins investigating crimes committed between 1998 and 2000, the period of forced disappearances.

Reduced sentences for information

In an innovative move, the Geneva meeting proposed a two-pronged approach, both judicial and humanitarian, often seen as conflicting. On the one hand, the judicial path consists of finding “positive synergies” between the various tribunals and the cases of the disappeared. Concretely, the idea is to offer suspected perpetrators reduced sentences or withdrawal of certain charges from the indictment in exchange for information about the location of mass graves. That may also mean guaranteeing protection of the witnesses or, in exceptional cases, giving them a new identity and host country. Let us remember that until recently the mandate of international criminal tribunals like the one for former Yugoslavia was to punish the perpetrators of war crimes but not participate actively in obtaining information about the location of mass graves and returning bodies to their families.

The Geneva roundtable also recommended that this first judicial approach be complemented by a second, purely humanitarian one. The idea is to create a conducive environment where witnesses or perpetrators of crimes can give information voluntarily with full confidentiality, without the risk that information be passed on to a tribunal. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which is strong on the principle of confidentiality, is to play a key role in this.

Climate of confidentiality

This two-pronged approach, both judicial and humanitarian, aims to be pragmatic, affirming the right to justice but also providing a non-judicial mechanism to increase the chances of obtaining precious information. The two-pronged approach draws lessons from the experiences of two countries, Argentina and Cyprus.

In Argentina, the mothers and grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo managed to find information about many of the 30,000 disappeared in that country, conducting a campaign that succeeded in ending the amnesty law that had protected the assassins for 20 years. It was only through the work of the courts that the fate of the disappeared became known, the circumstances of their deaths elucidated and sometimes their bodies found, and that the soldiers responsible for these crimes were identified and punished. In Cyprus, the United Nations, in agreement with both the Greek and Turkish authorities on the divided island, resolutely chose the non- judicial path. The UN set up The Committee on Missing Persons (CMP), offering total confidentiality (and so no prosecutions) to anyone providing information about the mass graves. In theory, there could still be justice – but without the courts getting any information given to the CMP -, but in reality justice has so far remained a dead letter.

This two-pronged approach, both judicial and humanitarian, proposed by the Geneva meeting is a hopeful development. It remains to be seen if it will allow light to finally be shone on the fate of Kosovo’s disappeared 20 years on. It will be watched closely in the rest of the world, where tens of thousands of families live every day with the torture of not knowing what happened to a loved one who was forcibly disappeared.