As the world celebrates International Justice Day this July 17, the peace versus justice debate continues in Uganda, the Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mali and many other countries. On the one hand is the legitimate desire for justice of victims, often scarred forever in their bodies and minds by the crimes inflicted on them. On the other hand is the necessity for governments to rebuild torn and divided societies. JusticeInfo this week looked again at this ongoing dilemma.

The most emblematic case in Africa is Uganda and the terrible Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), whose top commanders are wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC). As JusticeInfo’s editorial advisor Pierre Hazan reminds us, an amnesty law adopted in 2000 led to thousands deserting from the LRA, thus weakening the rebel group led by Joseph Kony.

But human rights defenders slammed the amnesty law, saying it was a violation of international law. So since 2015 Uganda, which is a member State of the ICC, has been planning to make its amnesty provision more restrictive, excluding perpetrators of international crimes (war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide) from eligibility. Ugandan Members of Parliament are nevertheless hesitating to adopt the amendment, arguing the dividends of the initial amnesty law.

“The proponents of amnesty also say that the judicial approach is not suited to LRA fighters, because many of the perpetrators are also victims,” writes Pierre Hazan. Indeed, many LRA fighters have been recruited by force, some when they were very young, and often forced to commit crimes. We should not forget either that no-one from the Ugandan army has yet been prosecuted, although some of its members are also suspected of committing serious crimes.

“How best to reconcile the need for justice and reconciliation and the need for stability? ” asks Pierre Hazan. “Can there be peace without justice?”

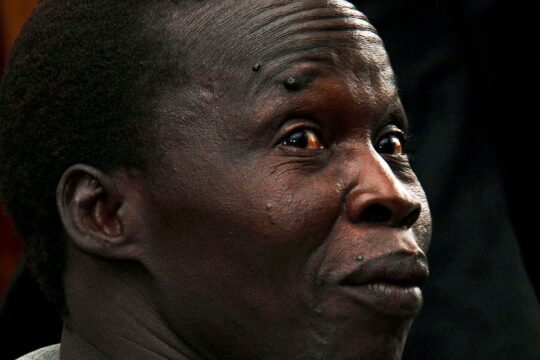

An amnesty is also what Central African warlord Nourredine Adam wants, although he does not say so explicitly. Adam, former Number Two of the Seleka rebel coalition that ousted president François Bozizé in March 2013, is already under international sanctions and liable to prosecution before a Central African court or the International Criminal Court (ICC). He is currently in the northeast of the Central African Republic. In a telephone interview with Radio Ndeke Luka, he called for a “national dialogue and a political accord” that would satisfy “everybody”. He clearly wants impunity for the crimes of which he is accused or may be accused. Former presidents François Bozizé and Michel Djotodia want the same thing, and are even supported in this by certain African governments. At the same time, an overwhelming majority of Central Africans want justice to be done.

An issue of a different nature has arisen in Tunisia after the “Arab Spring”. Now, writes correspondent Olfa Belhassine, the Court of Audit is accusing the government of having recruited as public servants people “falsely represented as injured” and family members of “pseudo martyrs of the Revolution, who have no link to the bloody clampdown by security forces”. Under a new Tunisian law, victims of the 2010-2011 Revolution have a right to “direct and exceptional recruitment into public administration” without having to compete.