There is no justice without reparations. That is all the more true when it comes to international crimes. But the mechanisms of reparation are still problematic, whether at the International Criminal Court (ICC) or in national transitional justice systems like in Côte d’Ivoire.

More than three years ago, the ICC sentenced former Congolese militiaman Germain Katanga to 12 years in jail for complicity in crimes against humanity and war crimes linked to the February 24, 2003 massacre in the village of Bogoro, in Ituri. On March 24, 2017, the judges evaluated at 3.75 million dollars (3.2M €) the physical, material and psychological damage done to the 297 victims recognized by the Court, and ordered Germain Katanga to pay 1 million dollars (853,000€). They decided that each victim should receive a symbolic 250$ (213€). In addition, they ordered collective reparations, to be worked out by the Trust Fund for Victims.

On July 25, the Trust Fund submitted to the judges its future reparations plan. The submission of this report is another step in a process which is likely still to be very long and very complex, as JusticeInfo’s correspondent in The Hague Stéphanie Maupas writes.

Lack of transparency in Côte d’Ivoire

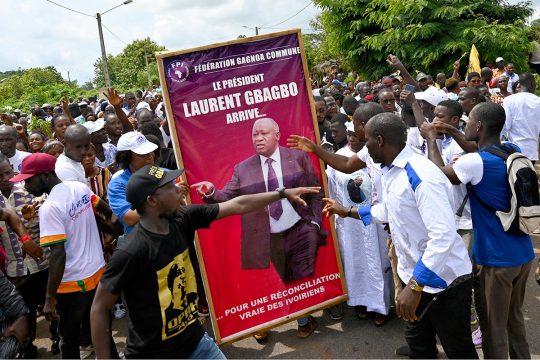

In Côte d’Ivoire, the transitional justice system set up by President Alassane Ouattara after the 2010-2011 post-election crisis also provided for reparations mechanisms. History is now starting to prove right those who from the beginning doubted the credibility of a process launched by Ouattara, himself a party to the crisis in question. In an interview with JusticeInfo.Net, President of the Ivorian Human Rights League (LIDHO) Pierre Kouamé Adjoumani drew a mixed picture of the two ad commissions that have followed each other since July 2011. This activist thinks the system has been weakened especially by a lack of transparency, leading to the drawing up lists of victims which are not very credible. He hopes President Ouattara understands that “such important issues concern the life of the whole nation”, and urges the government to work with civil society to correct imperfections.

September 2009 massacre in Guinea

Justice and reparations are what is wanted by victims of the bloody repression of an opposition rally on September 28, 2009 in Guinea’s capital Conakry. That day, soldiers killed at least 157 people and raped 109 women in a Conakry stadium, where thousands had gathered to protest against the presidential candidacy of Moussa Dadis Camara, head of the military junta at that time. On July 28, two months from the eighth anniversary of the massacre, human rights organizations and victims called for investigations by Guinean judicial authorities to conclude. Moussa Dadis Camara now lives in exile in Burkina Faso, where he was indicted in July 2015 by Guinean magistrates for his suspected involvement in the massacre. His former close aide Aboubakar Sidiki Diakité, extradited from Senegal to Guinea in March, is also one of the suspects.