As the world marks International Day of the Disappeared on August 30, learning the fate of the tens of thousands of Afghans who have been victims of enforced disappearance over the past four decades seems ever more remote. For their family members, that failure is like a wound that has never healed.

Four years ago, Mohammad Rahim’s family finally held funeral services for him – 34 years after Afghanistan’s secret police took him away, never to be seen again.

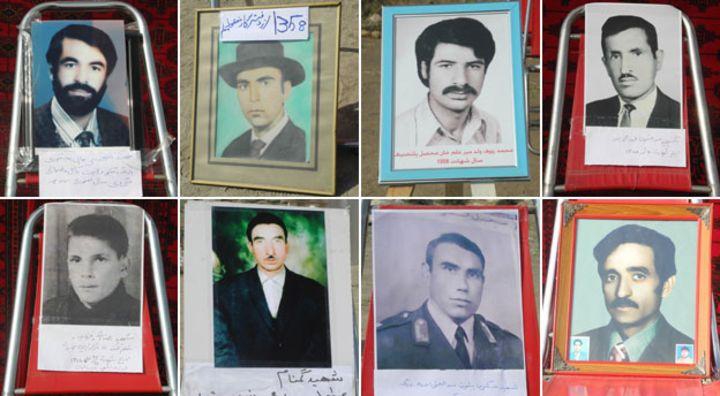

The ceremony took place after Rahim’s name finally appeared on a “death list” of people detained and ordered executed in 1978-79. The list is the only official confirmation of the victims’ fate the families have ever received. Five thousand names are on it – a fraction of those who “disappeared” after the communist People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan seized power, launching a civil war that, with changes in the warring factions, continues today.

A literature student in Paktia province, Rahim was caught up in a purge of teachers, civil servants, religious leaders, and tribal elders accused of “anti-revolutionary” sympathies. More than 27,000 people disappeared in Kabul alone – and possibly 100,000 across the country – in just 20 months. Most were buried in mass graves that have yet to be exhumed.

The state prosecutor for the Netherlands obtained the “death list” as evidence against Amanullah Osman, an Afghan intelligence official who had sought asylum in the Netherlands in 1993, but the investigation came to an abrupt end when Osman died in 2012. Dutch authorities said they published the list to “bring closure to the tormenting uncertainty that thousands of Afghan relatives have lived in for years.” A Facebook page, “5,000 Victims,” serves as a memorial for this and other atrocities of the war; recent postings concern Hezb-i Islami leader Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, accused of abducting and secretly killingAfghan intellectuals, journalists, and others in the 1980s and 90s.

But enforced disappearances continue to this day. A recent United Nations report on torture in Afghanistan cites numerous accounts of people vanishing after being taken into custody by the police in Kandahar in 2015 and 2016.

The Afghan government should promptly ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance, and implement its provisions. It should work with UN and other agencies to uncover the fate of those disappeared, however long ago. Where possible, the authorities should prosecute those responsible. For the sake of those families still awaiting answers, the government should do all it can to uncover the truth.

This article was previously published by Human Rights Watch