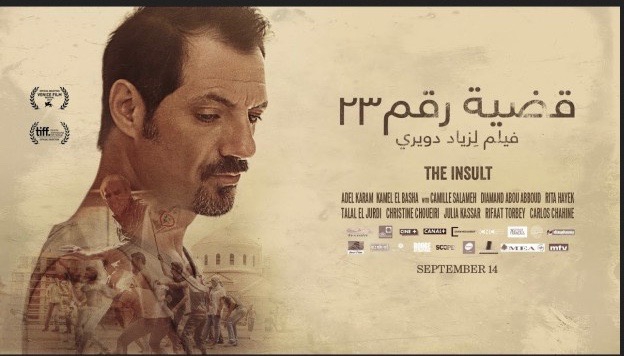

Nearly three decades after it ended, Lebanon's civil war returned to haunt Beirut this week at a screening of the film "The Insult," which forcefully explores the taboos of the conflict.

The movie opened to rave reviews at the Venice Film Festival, earning accolades for its French-Lebanese director Ziad Doueiri and a Volpi Cup for Palestinian actor Kamel El Basha.

The advance screening on Tuesday was overshadowed somewhat by Doueiri's brief detention for filming in 2012 in Israel despite Lebanese legislation banning citizens from visiting the Jewish state.

But viewers still packed multiple halls Tuesday night to watch the film at a cinema in central Beirut, which was ravaged by the bitter 1975-1990 war that divided Lebanon's capital.

"The Lebanese civil war haunted me all the way to Los Angeles," Doueiri, who fled war-ravaged Beirut in 1983, told AFP.

"The division between east and west Beirut stayed with me even though the war ended, the checkpoints reopened, and the capital was reunited."

"The Insult" is Doueiri's second movie about the civil war, after his 1998 film on teenage life in the battle-torn capital, "West Beirut".

The conflict erupted in 1975 between Lebanese Christians and armed Palestinian factions and eventually drew in Syria, Israel, the United States, and other Western countries.

The 1990 peace accord that ended it never brought a reconciliation process.

Instead, Lebanon's parliament issued a general amnesty absolving all parties of war crimes.

- Opening old wounds -

Almost 20 years later, "The Insult" carves out an ambitious goal: opening old wounds to pave the way to a much-needed, if belated, redemption.

The movie, set in the post-war era, centres around a legal dispute between Christian nationalist Tony, played by Lebanese actor and comedian Adel Karam, and Palestinian refugee Yasser, played by Basha.

A disagreement between the men over a water pipe snowballs into a court case and then into a violent, national crisis, opening up a Pandora's box of old grievances, prejudices, and trauma.

The film has been praised by Lebanese critics for dealing frankly with the unresolved issues of the civil war.

"The movie opens a necessary window to look on the remnants of Lebanese memory that we are not allowed to go near, discuss, or ask questions about," Lebanese movie critic Nadim Jarjoura told AFP.

"The Insult also deals with a lot of other issues, including reconciliation with oneself. You cannot reconcile with the other without reconciling with yourself," he added.

"You need to return to the past to leave it."

The film contains sequences of forceful language and communal tension rarely depicted in Lebanese cinema.

"Sharon should have annihilated you," Christian Tony screams at Palestinian Yasser as their tiff escalates into a feud, referring to Israel's former prime minister Ariel Sharon.

Sharon was accused of "indirect" responsibility for the 1982 massacre of hundreds of Palestinians by Israel's Lebanese Christian Phalangist allies in Beirut's Sabra and Shatila camps.

- 'Still at war' -

Tony in turn finds himself assaulted with screams of "Zionist dog" during a court hearing between the men, evoking the still-controversial alliance that formed between some Christian factions and the Jewish state against Palestinians in Lebanon.

"There's no side in the war that can say it, alone, was persecuted," 54-year-old Doueiri told AFP.

"No single side can say it was the only one that was hurt. There will always be another side that has the right to say that the war spilt its blood, too."

"The Insult" depicts the Lebanese as not yet having turned the page on the civil war, while their country is riven by new divisions including tensions related to the conflict in neighbouring Syria and the issue of the arsenal of the powerful Lebanese militant group Hezbollah.

When Tony's lawyer asks if he would take up arms today, he replies: "We're still at war."

"I'm not Jesus Christ to turn the other cheek," he says elsewhere in the film. "No, we are not all brothers."

The film offers no easy answers, but a path to gradual reconciliation emerges between the men.

The screening ended with a heavy silence, with the audience sitting quietly as the titles scrolled.

But it provoked discussions, including between a father and son who were still locked in animated debate nearly an hour later.

"You can't think like that, Dad, the civil war is over," the teenager could be heard telling his white-haired father.