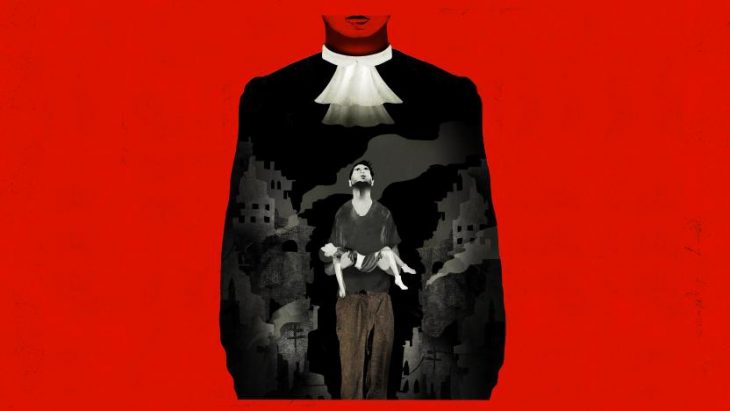

Over the last six years the Syrian crisis has claimed the lives of an estimated 475,000 people as of July 2017, according to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights. All sides to the conflict have committed serious crimes under international law amid a climate of impunity.

A range of groups have actively documented violations of human rights and humanitarian law in Syria. In late 2016, the United Nations General Assembly also created a mechanism tasked with analyzing and collecting evidence of serious crimes committed in Syria suitable for use in future proceedings before any court or tribunal that may have a mandate over these crimes.

But for the most part, the wealth of information and materials available has not helped to progress international efforts to achieve justice for past and ongoing serious international crimes in the country. Syria is not a party to the International Criminal Court, so unless Syria accepts the court’s jurisdiction voluntarily, the court’s prosecutor needs the United Nations Security Council to refer the situation in Syria to her in order to open an investigation there. However, in 2014, Russia and China vetoed a Security Council resolution that would have given the prosecutor such a mandate. And neither Syrian authorities nor other parties to the conflict have taken any steps to ensure credible accountability in Syria or abroad, fueling further atrocities.

Against this background, efforts by various authorities in Europe to investigate, and, where possible, prosecute serious international crimes committed in Syria, may provide a limited measure of justice while other avenues remain blocked.

The principle of “universal jurisdiction” allows national prosecutors to pursue individuals believed to be responsible for certain grave international crimes such as torture, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, even though they were committed elsewhere and neither the accused nor the victims are nationals of the country.

Such prosecutions are an increasingly important part of international efforts to hold perpetrators of atrocities accountable, provide justice to victims who have nowhere else to turn, deter future crimes, and help ensure that countries do not become safe havens for human rights abusers.

This report outlines ongoing efforts in Sweden and Germany to investigate and prosecute individuals implicated in such crimes in Syria.

Drawing on interviews with relevant authorities and 45 Syrian refugees living in these countries, the report highlights challenges that German and Swedish authorities face in taking up these types of cases, and the experience of refugees and asylum seekers in interacting with the authorities and pursuing justice. In so doing, this report draws valuable lessons for the countries involved and other countries considering investigations involving grave abuses committed in Syria.

The report finds that both countries have several elements in place to allow for the successful investigation and prosecution of grave crimes in Syria—above all comprehensive legal frameworks, well-functioning specialized war crimes units, and previous experience with the prosecution of such crimes. In addition, due to the large numbers of Syrian asylum seekers and refugees in Europe, previously unavailable victims, witnesses, material evidence, and even some suspects are now within the reach of the authorities. As the two largest destination countries for Syrian asylum seekers in Europe, Germany and Sweden were the first countries in which individuals were tried and convicted for serious international crimes in Syria.

Nonetheless, both countries have faced difficulties in their efforts. On one hand, authorities pursuing cases on the basis of universal jurisdiction encounter challenges that are inherent to these types of cases, and solutions to some of these challenges are beyond the reach of authorities. For example, these cases are usually brought against people present in the territory of the prosecuting country and authorities cannot control whether or not certain individuals will travel to their country at a specific time.

On the other hand, the standard challenges associated with pursuing universal jurisdiction cases are compounded, in the case of Syria, by an ongoing conflict in which there is no access to crime scenes. As a result, authorities in both countries have been compelled to turn elsewhere for information, including from Syrian asylum seekers and refugees, counterparts in other European countries, UN entities, and nongovernmental groups involved in documenting atrocities in Syria.

According to practitioners and refugees Human Rights Watch interviewed in Sweden and Germany, gathering relevant information from Syrian refugees and asylum seekers has proved difficult due to their fear of possible retribution against loved ones back home, mistrust of police and government officials based on negative experiences with Syrian authority figures, and feelings of abandonment by host countries and the international community. “Our disappointment is not from the regime, we know the regime, we survived the regime,” one Syrian activist told Human Rights Watch. “Our disappointment is with the world. They use human rights when they need it.”

The report also documents a lack of awareness among Syrian asylum seekers and refugees in Sweden and Germany about the systems in place for the investigation and prosecution of grave crimes, the possibility of their contributing to domestic justice efforts, or the right of victims to participate in criminal proceedings. Most Syrian refugees interviewed were either unaware of ongoing and completed proceedings related to Syria, or had limited or inaccurate information about the cases. Others had unrealistic expectations about what national authorities could deliver by way of accountability given different constraints they face.

Recognizing these issues, authorities in both countries are working to address some of them through various outreach efforts, although more needs to be done and limited resources and mandates constrain efficacy. In addition, authorities need to balance facilitating contact, input and information sharing with potential victims and witnesses with confidentiality requirements inherent in criminal investigations, the risk of being overwhelmed with potentially vast amount of information, and managing expectations of what they will be able to deliver and when to victim communities and the public at large.

Authorities in Sweden and Germany reported that the existence of efficient protocols at the European level has led to good cooperation related to Syria cases, but said they have had limited or no contact with countries neighboring Syria. They have also started to reach out to nongovernmental and intergovernmental actors, including the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria, although authorities said that cooperation was slow and that, because of their different mandates, the information collected by these entities while useful at the investigation stage might not meet domestic thresholds for admissible evidence in criminal proceedings.

While any credible criminal proceedings that lead to accountability for crimes committed during the conflict are welcome, the reality is that the initial few cases authorities have been able to successfully prosecute within their jurisdictions are not representative of the scale or nature of the abuses committed in Syria.

The few cases to reach trial have mostly implicated low-level members of ISIS, Jabhat al-Nusra, and non-state armed groups opposed to the government while only one has addressed alleged crimes committed by a low-level member of the Syrian army. In Germany, practical and jurisdictional limitations, such as difficulties finding evidence linking alleged perpetrators to underlying crimes, have also made it easier to bring terrorism charges rather than prosecute for war crimes or crimes against humanity. Terrorism offenses are easier to prosecute because authorities only have to prove connection between the accused and a labeled terrorist organization. However, terrorism charges do not reflect the extent of crimes committed.

Terrorism prosecutions, or prosecutions of low-ranking members of armed groups, should not substitute for efforts to successfully prosecute grave crimes committed by senior officers that are likely to more directly promote compliance with international humanitarian law and ensure justice for grave crimes.

There is also the problem of perception. The use of terrorism charges without significant efforts to pursue prosecutions for war crimes or crimes against humanity, where there is indication that such international crimes were committed, could send the message that the authorities’ only focus is to combat domestic threats. Efforts to pursue terrorism charges can and should go hand in hand with efforts and resources to investigate and prosecute war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide.

Syrian refugees interviewed by Human Rights Watch in both countries expressed frustration that cases prosecuted to date reflect neither the full spectrum of the perpetrators nor of the atrocities committed in Syria. In particular, they said, the lack of cases brought against individuals affiliated with the Syrian government led them to question the balance and fairness of the proceedings overall.

In order to address some of the challenges authorities are facing, Sweden and Germany should ensure that their war crimes units are adequately resourced and staffed, provide them with ongoing training, and consider new ways to better engage with Syrian refugees and asylum seekers on their territory.

Overall, the limited nature of the proceedings to date highlights the need for a more comprehensive justice process to address the ongoing impunity in Syria, and means to engage as many jurisdictions as possible where fair and credible trials can be pursued. A number of potential perpetrators, including high-level officials or senior military commanders affiliated with the Syrian government, are unlikely to travel to Europe. To fill this gap, a multi-tiered, cross-cutting approach will be needed in the long-term which, in addition to proceedings under universal jurisdiction, should include other judicial mechanisms at the international and national level.

The full report is available on HRW's website