An enormous scandal has hit the International Criminal Court (ICC). After six months of investigations, eight international media of the European Investigative Collaboration (EIC) have produced findings that seriously undermine the ICC’s credibility and image of impartiality. They examined 40,000 confidential documents – diplomatic cables, banking documents and correspondence – obtained by French investigate website Mediapart. These documents throw for the first time a raw light on the political games of States around international justice and the dubious morality of Luis Moreno Ocampo, who was the ICC’s first Prosecutor from 2003 to 2012.

Current ICC Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, clearly embarrassed, issued a statement in which she said she was opening an investigation particularly into two members of her team said to be in close contact with Ocampo. Bensouda also stated that she had “in the past, personally made my position on this clear to Mr Ocampo and have asked him, in unequivocal terms, to refrain from any public pronouncement or activity that may, by virtue of his prior role as ICC Prosecutor, be perceived to interfere with the activities of the Office or harm its reputation.”

Gbagbo jailed without legal basis

A confidential document from French diplomatic sources reveals that in 2011 the International Criminal Court asked for Côte d’Ivoire’s ex-president Laurent Gbagbo to be kept in detention, even though at the time there was no arrest warrant and the ICC had not been seized of the case. According to Mediapart, which obtained correspondence between Ocampo, French diplomats and the new Ivorian president Alassane Ouattara, their political analysis was the same: Laurent Gbagbo must be kept in jail to prevent destabilization of Côte d’Ivoire, even if there was no judicial basis. As Mediapart points out, there was at that time “no solid evidence pointing to Gbagbo’s responsibility in crimes against humanity which could fall under the ICC’s jurisdiction, since the Court had not yet sent any investigators to Côte d’Ivoire”. But the issue was delicate because no doubt Gbagbo’s men had committed crimes, but also supporters of Alassane Ouattara and perhaps French troops too. Mediapart asks whether Ocampo was not knowingly complicit in a settling of political scores to the benefit of one side only, without any procedural framework.

Ocampo loses moral compass in Libya

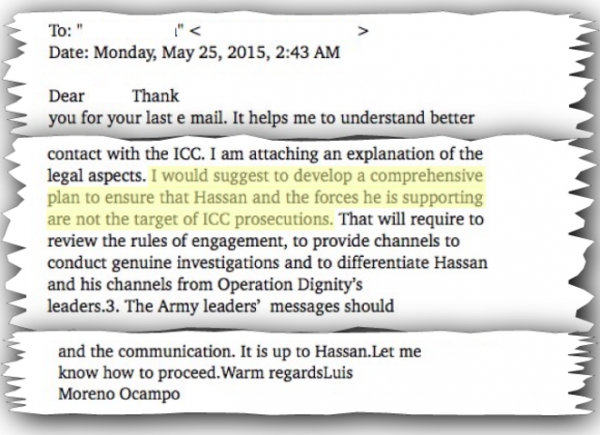

In June 2011 Luis Moreno Ocampo, who was at that time ICC Prosecutor, issued an arrest warrant against former Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi for crimes against humanity, but was not able to try him because Gaddafi was killed soon afterwards. Four years later, in 2015, Ocampo was again working on Libya, but in a very different role. No longer hunting war criminals, he had become the lawyer for powerful men whose soldiers cared little for international humanitarian law. Ocampo was working for American law firm Justice First, whose clients included Libyan businessman Hassan Tatanaki, formerly close to Gaddafi and now ally of General Haftar, one of the most powerful men in Libya. Haftar’s troops are waging a merciless war with no regard for the Geneva Conventions. When Ocampo learned that Bensouda, his successor as ICC Prosecutor, planned to prosecute General Haftar, he worked not only to get Haftar’s enemies indicted but also to protect Hassan Tatanaki, Haftar and his men from any move to prosecute them. This was not necessarily going to be easy: on a television station belonging to Hassan Tatanaki, the commander of Haftar’s airforce was promising to massacre traitors and rape their women. But Ocampo did not fear the task. “I would suggest to develop a comprehensive plan to ensure that Hassan and the forces he is supporting are not the target of ICC prosecutions,” he wrote. And so the man who had been the first sheriff of international justice had become the advocate for a group of men no doubt responsible for war crimes. He got 750,000 dollars for those three months of work.

Kenya and the Ocampo U-turn

In 2010, the International Criminal Court accused six Kenyan officials, including current Head of State Uhuru Kenyatta, of crimes against humanity committed in 2007. Since then the whole case has collapsed. EIC’s investigation tells how ex-Prosecutor Ocampo, after indicting Kenyatta, worked behind the scenes to offer him “an honourable way out”. Even though he had left the ICC a year earlier, Ocampo was working secretly on a strategy that would enable dropping of the procedures that he himself had launched against Kenyatta! In September 2013, he told a member of New York law firm Shearman & Sterling that he had spoken with ICC Prosecutor Bensouda about the idea of “organizing a group of external lawyers to examine the evidence in the Kenyatta case”. “I do not think it is possible to prosecute a Head of State with a weak case,” he wrote. So Ocampo tried to influence the contacts that he had maintained within the Office of the Prosecutor. “Various people have told me there is no evidence,” he said. “Witnesses have withdrawn their testimonies and others have refused to appear before the court. I understand the difficult political environment, but when there is no evidence, a prosecutor should not go to court.” Ocampo even contacted Kofi Annan, head of the international mediation for Kenya. “It is time to find an honourable way out for Kenyatta,” he wrote in an incredible about-turn. Why did the man who indicted Kenyatta then want to let him off? What were the reasons for this U-turn? Was there a lack of evidence? Or was it to satisfy the US which did not want to alienate Kenya, a key ally in the fight against Al Shabab in Somalia?