“Deflagrations: Children’s drawings and adult wars”, a book published by Anamosa, recounts war in 150 children’s drawings. The book is accompanied by an exhibition until December 16 at the André Malraux médiathèque in Strasbourg. This is a beautiful book which appeals for peace.

Colourless corpses, huts on fire, columns of refugees, bombing, fear and sadness. The 150 drawings put together by Zérane Girardeau tell of war through children’s eyes. The book “ Déflagrations, dessins d’enfants, guerre d’adultes”, published by Anamosa, reproduces a century of children’s drawings during war, the work of young witnesses from the First World War to the conflict in Syria. “These drawings allow us to situate ourselves for a moment outside the undifferentiated stream of images around us,” writes project coordinator Zérane Girardeau. “It is like an antidote to the indifference of habit, which ends up transforming horrors into background noise or far-away fiction. It helps us to keep our eyes open, to not forget, continue to be aware and not anaesthetize emotion.”

There is emotion behind these drawings and sometimes their captions, like the Chechen child who asks if “Father Christmas will manage to reach us, or will he be stopped at a checkpoint?” These drawings by children of 5 to 17 reveal hundreds of accounts telling the same story, enriched by the contributions of artists, psychologists, journalists and jurists. Françoise Héritier, an anthropologist who died on November 15 in Paris, contributed one of her last texts. She speaks of the “deafening silence” represented in these drawings. “They saw, they ran, they hid, and they tried to remain silent so as not to draw attention, but they heard all the noise” of the war, she writes. The past century has given us the UN Charter, the Geneva Conventions and a Convention to protect children in armed conflict. But the promise of “never again” has not been upheld, and these drawings remind us of that. They are a representation of “universal violence”, says François Héritier, and “nothing in these testimonies is imagined”.

In 2007, the organization Waging Peace sent 500 children’s drawings to the Prosecutor’s office at the International Criminal Court (ICC), which have been included as contextual evidence in the Darfur case. Jurist Olivier Bercault, a professor at the University of San Francisco and former investigator for the emergency team of Human Rights Watch (HRW), told JusticeInfo how he was struck in 2005 by the testimonial strength of drawings by refugee Sudanese children in the camps of Chad.

Olivier Bercault: I went with a Human Rights Watch doctor to gather testimonies on what was happening in Darfur. There were many children, and they were delighted to see visitors. So it was a bit of a celebration, but we had trouble talking to the adults. To keep the kids quiet, we gave them paper and crayons. We didn’t ask them to do anything, but they started drawing the most amazing, very precise images of the war. In them we could see the attacks on the towns, the arrival of the Janjaweed [pro-government militia in Darfur], the bombing, the killing, even images of rape. So we repeated this experiment in other refugee camps, and we gathered hundreds of drawings. Then we asked the teachers – Darfur teachers working in UNICEF schools in the refugee camps – if they had more such drawings. They showed us school books full of them. They said: “Take them and tell the world what we have been through.” This was not at all what we had set out to do, but suddenly we felt committed to these children.

JusticeInfo: Did you think immediately that these drawings could constitute evidence before a court?

Initially I did not think about the judicial aspect, but I will remember that first drawing all my life. I saw that child drawing the Janjaweed and I was completely fascinated. It was exactly what I knew of the Janjaweed. There are very few photos or videos of that militia. In the beginning I did not think the drawing could be used by a tribunal. I did not think that far, I only though that it corresponded well with what I knew. I had worked for several years in Darfur, and I had a good idea of what was going on. We had already interviewed hundreds of victims, we also had aerial photos, but we did not have visual images. We may be there before or after the event, but no-one is there when the crimes are taking place. And all of a sudden we had this visual representation of the crimes. It was only afterwards that we thought the drawings could be evidence in a trial. And then came the decision of the International Criminal Court.

What do we learn from these children’s drawings?

The work of an organization like HRW is to establish a working method. For days and months we listen to victims. If at the end of my mission I have testimonies showing that on that day villages were attacked, the air force started bombing, soldiers arrived on foot followed by the Janjaweed, if I have 80 to 100 testimonies that tell the same thing, then I can start to establish the facts. In Darfur, all the children tell the same thing with their crayons. Their drawings are obviously not the same, but they show the same way of operating. And from there, yes, they can become evidence.

Is it difficult to gather such testimonies?

When you gather testimonies from adults, people who have been tortured or whose relatives have been killed, it is sometimes difficult. They describe situations which are very complicated, and sometimes they start shouting or crying. That is not the case with children. The children are joyful or calm, but the trauma is in the past. I remember a girl, very young, perhaps not yet six years old. She had drawn a woman lying on the ground with a red face. She told me this woman was dead. I asked her why the face was red, and she looked at me as if I were stupid. “Because they shot her in the head,” she said. She was six years’ old and she said that naturally, calmly. I do not know what kind of trauma she had grown up with.

When you look at this book, you are struck by the precision of the war scenes and the expression of feelings. Can you explain?

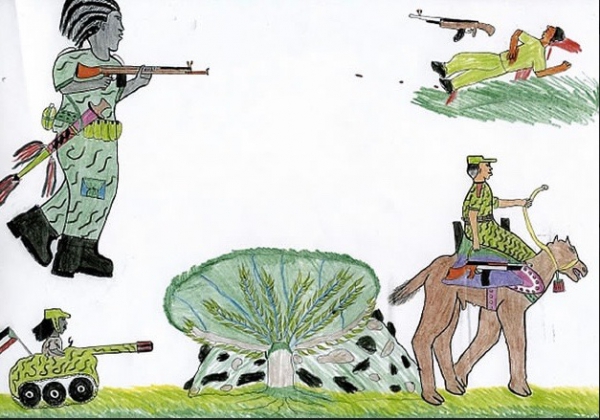

Some drawings from Darfur are very simple but express numerous situations. Flight and panic are represented by spread fingers, hair standing on end, mouths frozen into expressions of terror. Many of the Darfur drawings show colourless people who have died. The dead are in grey, while those who are alive are full of colour. Some drawings play on proportions to express something. There is fascinating precision in these drawings. If you compare the children’s drawings of weapons with photos of those weapons, you see that. The children do not draw in the same way a Tupolev, used by the Sudanese army, and a MIG fighter plane. They draw helicopters with military camouflage. They do not draw an American-made M16 like a Kalachnikov, that’s very clear. The Kalachnikov has a magazine shaped like a comma. An armed car and a tank do not have the same caterpillar tracks or the same number of wheels, that is obvious in a child’s drawing. They capture those things with their eyes, and the precision is amazing.

“Deflagrations” is a collection that covers more than a hundred years of war. Do you see things in common in all these drawings?

There are similarities in the way that soldiers and weapons are drawn, as well as the attacks. That is most striking with the attacks from the air, no doubt because they are the most terrifying, especially when you are a child. But education also plays a part. There are some countries where art education was not a priority. There are some drawings that are very good but there is no use of perspective, no density. If you look at the drawings of the Second World War in France, you can sense that these kids had an education in art. I think there are cultural similarities. If you take the drawings from Algeria or Iran, they are very colourful and dense. The drawings from Africa are much lighter, there is a lot more space. The European drawings use perspective, there is a whole school of teaching behind them. There is a coherence in the styles.