They are on the frontlines of any major conflict or disaster – but how much is known about the daily experiences of humanitarian workers in these extreme situations? In their new book, Génocide et crimes de masse. L’expérience rwandaise de MSF (“Humanitarian Aid, Genocide and Mass Killings: Médecins sans frontières, the Rwandan experience, 1982-97”), Marc Le Pape and Jean-Hervé Bradol set out to answer some of these questions. The book is also informed by Bradol’s experience of working for Médecins Sans Frontières in Rwanda during the genocide. Here, they discuss their findings.

You investigated humanitarian operations in the Great Lakes region between 1990 and 1997. This was a period of extreme violence against Rwandophone populations. You specifically looked at the records of Doctors Without Borders in Paris. What did you hope to learn?

Marc Le Pape: The actual day-to-day work of humanitarian teams in situations of extreme violence is generally little known and understood. That’s why our investigations focussed on messages from the field, while most studies are far more concerned about getting the macro-political or macro-humanitarian picture. Taking a “micro” perspective meant we could observe the long-term evolution of operations: how, and with whom, did teams need to negotiate to launch and maintain operations?

So we looked at how these teams got information and communicated with political and military authorities, various local authorities, UN agencies in the Great Lakes region, local and international NGOs, religious leaders and people at emergency sites, in medical facilities and camps.

We also looked at the relationship between the field of operations, national capitals and the various Doctors Without Borders head offices. We tracked field accounts transmitted up the chain of command, how the organisation’s head offices reacted to the stories of violence, intimidation and prohibitions, and the way these were then framed and talked about publicly.

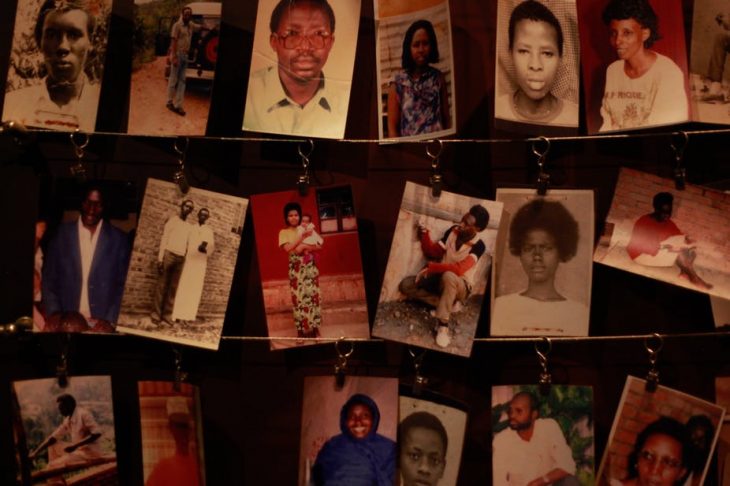

For example we examined all the documents, from internal alerts to public statements, demonstrating the gradual realisation of humanitarian workers in Rwanda in 1994 that they were witnessing the systematic, organised extermination of the Tutsi people.

Did humanitarian workers witness extreme violence?

Jean‑Hervé Bradol: It’s shocking to see, from 1994 onwards, the extent to which humanitarian workers became regular eyewitnesses to violence, murder and large-scale massacres. It is generally rare for humanitarian workers to witness these kinds of events. They typically work at a distance from mass killing sites and the perpetrators remain largely anonymous. This was not the case in Rwanda.

The situation in April 1994 was extreme and basically unprecedented, at least for Doctors Without Borders. Humanitarian workers where present when the decision was made as to who would die and who would be spared. Some Rwandan staff members were among the victims. Others were complicit, or even participated in these crimes.

Can you give a few examples of the violent situations Doctors Without Borders workers witnessed and what kind of lessons were learned – or not?

Jean‑Hervé Bradol: In April 1994 I was working in Kigali. In the first few days following the assassination of former president Juvénal Habyarimana, we braced ourselves for a massive eruption of violence. We thought there would be reprisals against the Tutsi, but never imagined that the order would be to “kill them all”.

Our team quickly realised that, at least in Kigali, the extermination of the Tutsi did not arise from chaos; instead, it was organised. Others also rapidly grasped the situation, in particular the head of the International Committee of the Red Cross delegation. It was awful. We knew the army was providing arms to the militia groups manning the road blocks. This made it extremely dangerous to evacuate wounded Tutsi adults to the Red Cross hospital: when they were caught, they were executed.

Later, Doctors Without Borders workers also witnessed first-hand the horror of the prisons in Rwanda. Between September 1994 and May 1995, they worked in Gitarama, where 3,000 prisoners were incarcerated in a complex built for 400 detainees. Some 800 prisoners died during this period. These people were arrested based solely on hearsay. We were their doctors, so we could not escape the realities of the new regime’s policy and the crimes committed by the former rebels.

Among other shocking crimes committed by the new authorities was the Kibeho massacrein April 1995. The new Rwandan (formerly rebel) army killed several thousand people in an internally displaced persons refugee camp in front of a Doctors Without Borders medical team. People convinced themselves that one mass crime, the Tutsi genocide, could hide other mass crimes committed by the new government.

As a sociologist, did you learn things that you had not realised were important to aid NGOs?

Marc Le Pape: I learnt the extraordinary importance of counting populations: the numbers of people in camps and on the run, of victims and of people being treated.

Conducting frequent counts is of course crucial for humanitarian organisations, especially when they need to know how many supplies to bring to the field. In the case of emergency NGOs, counts are also politically important to back up first-hand accounts, ensure that the murders they have witnessed are documented, and oppose competing statements that claim to be based on figures.