Forty-three years ago today, the Khmer Rouge took power in Cambodia. Their radical regime, led by the dictator Pol Pot, inflicted countless atrocities and left deep wounds. Neighbors turned against one another. Families were fractured. Political cleavages deepened. An estimated 1.7 million people died. Almost everyone suffered personal trauma.

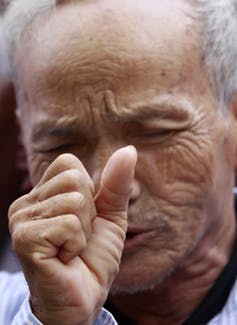

Survivors are still in the long process of seeking reconciliation, or putting the pieces back together in lives and societies shattered by conflict.

Yet the measures taken to address political and social conflict are not always conducive to personal reconciliation – the journey of coming to terms with excruciating past experiences.

Reconciliation is one of the aims of transitional justice, the means by which societies address past crimes as they emerge from conflict or repression. As someone who studies this process in Cambodia, I am interested in how official efforts to promote justice and reconciliation affect individual survivors’ ability to heal.

Can efforts to exact justice end up injuring survivors again?

Research on such profound human suffering requires more than intellectual understanding of the legal and political mechanics of justice and reconciliation. It requires a human journey from sympathy to empathy and learning about the personal experiences of the survivors whom such initiatives aim to assist.

Can criminal trials heal survivors?

Cambodians endured staggering atrocities during the Pol Pot era. The Khmer Rouge regime repressed brutally any perceived resistance to its rule. Urban populations were sent to the countryside to perform forced labor. Families were split. Intellectuals were murdered. People accused of even slight infractions were imprisoned, tortured and often killed without any legal process.

The best-known effort to address crimes of the Pol Pot era is a series of trials backed by the United Nations and Cambodian government. The special tribunal they created more than a decade ago has yielded three convictions for crimes against humanity and other offenses – the first credible verdicts for crimes of the Khmer Rouge regime.

As my colleague Anne Heindel and I have written, the tribunal has faced many challenges. Its blend of Cambodian and international laws, procedures and personnel is cumbersome. Politicized feuds have arisen between the U.N. and Cambodian sides of the court.

Yet a more fundamental question surrounds its work: Do high-profile criminal trials help survivors heal?

Official statements on war crimes and genocide trials often stress their healing potential. In theory, trials can reveal truths, give voice to victims, express condemnation and satisfy survivors’ thirst for justice.

Reality is more complex.

The goals and requirements of a criminal process sometimes cut against the interest of promoting survivors’ personal reconciliation. For example, witness testimony is often crucial to a fair trial. But giving testimony can retraumatize victims. A focus on select defendants can produce a skewed and partial exposure of the truth.

These trade-offs challenge researchers trying to evaluate transitional justice efforts. Which goals should matter most? Securing credible criminal convictions? Clarifying the historical record? Helping survivors work through trauma? And what role does academic research play in determining which values should get priority?

Seeing through others’ eyes

I grapple with these questions myself. They challenge me to reflect on how my values and interests shape my research, sometimes in tension with the expressed needs of survivors.

One example occurred in July 2010, after the Khmer Rouge tribunal issued its first conviction. The defendant was Duch, the notorious former head of a Khmer Rouge security center known as Tuol Sleng. By overwhelming evidence and his own admission, Duch was found guilty of overseeing the torture and arbitrary execution of thousands of innocent Cambodians.

The judges sentenced Duch to just 19 years in prison. They reasoned that Duch had been detained illegally for years by Cambodian authorities and was entitled to a meaningful remedy – which meant something shorter than a life sentence.

Some human rights groups and international lawyers applauded the court’s stand for the defendant’s rights. Many victims were outraged that an architect of mass murder could receive such a light sentence.

As a scholar of international criminal law, interested in how principles of due process are developed, my first instinct was to applaud.

But I also saw the depth of many survivors’ disappointment and anger at the sentence. It was an uncomfortable, humbling reminder that what professionals see as proper process may not answer the profound needs of survivors. The values embedded in many studies of transitional justice do not necessarily match the legitimate desires of those who have suffered the gravest injustice.

Duch was later sentenced on appeal to life in prison, but his trial raised other issues related to personal reconciliation that have yet to be resolved.

Survivor testimony: Who benefits and who pays the price?

The clearest issue that needs resolution is victim testimony.

Some survivors have found appearing at the tribunal empowering and cathartic. Others have found the experience deeply unsettling. Sitting in a large courtroom, responding to cross examination and facing the gaze of robed judges and the accused is hardly a recipe for psychological comfort.

Survivors tell of deep personal losses or hardship. They tell of lost loved ones, of near starvation, and of witnessing or experiencing gruesome abuses. In some cases, they relate their stories while looking straight at their past tormentors.

Watching some survivors tremble as they enter or exit the courtroom has made me reflect on who benefits from justice and who pays the price.

When victims are simply accessories to the criminal process, they may experience more hurt than healing, as human rights scholar Eric Stover and others have shown.

To help survivors tell their stories with greater ease, the Khmer Rouge tribunal has allowed “statements of suffering,” which resemble victim impact statements in U.S. criminal courts.

Victims can narrate their stories without frequent interruptions for questions from judges and lawyers. Many provide gripping accounts of their personal and family experiences. In doing so, many stray from the alleged crimes of the accused into broader revelations of personal suffering.

But as Anne Heindel and I have discussed, these raise difficult questions of how to balance the rights of the accused with victims’ needs. Statements of suffering can undermine fair trials if they include questionable claims that defendants cannot challenge. Yet for victims, those statements are often the best opportunity to have their voices heard and to experience catharsis.

As researchers, we evaluate transitional justice mechanisms and thus can affect debates on how they are structured. We often bring useful technical knowledge and outside perspectives.

But “experts” often measure success very differently than ordinary survivors. We have an ethical responsibility to consider carefully the diverse preferences of survivors.

This means going well beyond the study of laws and institutions to embrace personal narratives and experiences in transitional justice research.

Getting from sympathy to empathy entails doing more than identifying practices we regard as effective. It requires trying to understand what survivors will see as success.

John Ciorciari is affiliated with the Documentation Center of Cambodia.