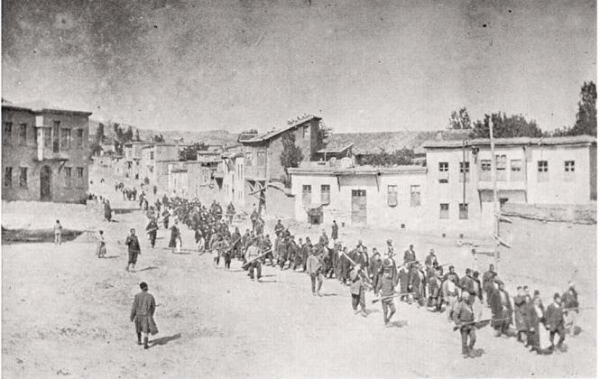

This week, JusticeInfo.net examined the significance of a memorial to the Armenian genocide recently inaugurated in a Geneva park.

“Despite opposition from Ankara, the “Streetlights of Memory” were inaugurated in Geneva after 10 years of judicial and diplomatic battles,” explains our Geneva correspondent Frédéric Burnand. “The work of artist Melik Ohanian pays tribute to the Armenians massacred over a century ago in Turkey and also to the many Swiss who mobilized to help them as soon as the massacres started. This is a message that still resonates today.”

“It is a good thing that Geneva and Switzerland have given a home to the Streetlights of Memory, because, like every tragedy, the Armenian one needs to be remembered,” writes JusticeInfo’s editorial advisor Pierre Hazan. “This is all the more necessary because denial remains strong.”

The Armenian genocide is not the first one recorded in contemporary history. Its tragic predecessor was the massacres of Hereros and Namas by the colonial army of Germany in what is now Namibia.

But it led Polish jurist Raphaël Lemkin -- comparing in his book Axis Rule over Occupied Europe the world’s failure to assist the Armenians in 1915-1916 and Jews in the Second World War -- to coin the term genocide. “He wanted to capture both conceptually and in legal terms a new, monstrous reality of war -- the extermination of civilian populations,” writes Pierre Hazan. “Lemkin was also the tireless architect of the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.”

These places of remembrance unfortunately do not prevent more mass crimes being committed, but they stand as guardians of history for the victims.

Victims have the right to “reparations”, which are one of the four pillars of transitional justice, according to a widely used definition by French jurist Louis Joinet. In a long interview, Pieter de Baan, Executive Director of the Trust Fund for Victims at the International Criminal Court, talks about the slowness of procedures. He says he can acknowledge “the frustration of the victims, the diminishing confidence that they may have”, but attributes this to a lack of human and financial means at his disposal. And as he admits, reparations “help to make the court relevant to society, beyond what is happening here in the courtrooms”.

Tunisia

Victims are also left asking questions in Tunisia, where the Truth and Dignity Commission is threatened with premature closure and has started transferring case files to specialized courts. Thirteen of these have been set up, explains our Tunis correspondent Olfa Belhassine. Two cases have already been transferred to these ad hoc chambers. One concerns the forced disappearance of Islamist militant Kamel Matmati, which has been sent to the specialized chamber in the southern town of Gabès; and one concerns the death under torture of Rachid Chammakhi, which has been sent to the chamber in Nabeul. “For all those in Tunisia fighting ongoing impunity in this first Arab Spring country, this is an important step in the establishment of a transitional justice process,” writes Olfa Belhassine. “Agents of the State, particularly in the security forces, will have to answer for what they did.”

JusticeInfo’s correspondent reminds us of the brutality of State repression. Kamel Matmati died under torture in October 1991 a few hours after being arrested, but the regime kept his death a secret. “So for years his wife, along with his mother, brought food and clothes to the Gabès police station for her husband whom she thought was still alive,” writes Belhassine “The two women described their struggle: for years they went from police posts to hospitals and prisons searching for their lost husband and son.” Matmati’s wife only learned the truth in 2009.