One of the most troubling trends of the armed conflict in South Sudan is the use of children as soldiers. South Sudan is among the ten countries with the highest number of child soldiers in the world. Yet political efforts to disarm, demobilize and reintegrate these child soldiers have been limited and challenging.

Since independence in 2011, South Sudan has experienced numerous violent struggles. And according to the United Nations, ever since the eruption of the civil war in 2013, both military and opposing armed groups in the conflict have recruited about 19,000 children as soldiers. In 2015, parties to the conflict signed the Agreement on the Resolution of the Conflict in South Sudan (ARCSS). In this accord, the warring parties agreed to refrain from recruiting and using child soldiers. However, in interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch (HRW), former child soldiers stated that commanders from both government forces and rebel groups have been abducting, detaining and forcing children, some as young as 13, into their ranks.

In instances where child soldiers have been used in armed conflict, various initiatives have been set up to make their return to communities as smooth as possible. These include disarmament, demobilization and reintegration (DDR). As stated in the Paris Principles and Guidelines on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Groups, “child reintegration is the process through which children transition into civil society and enter meaningful roles and identities as civilians, are accepted by their families and communities in a context of local and national reconciliation. Further, sustainable reintegration is achieved when the political, legal, economic and social conditions needed for children to maintain life, livelihood and dignity have been secured. This process aims to ensure that children can access their rights, including formal and non-formal education, family unity, dignified livelihoods and safety from harm.”

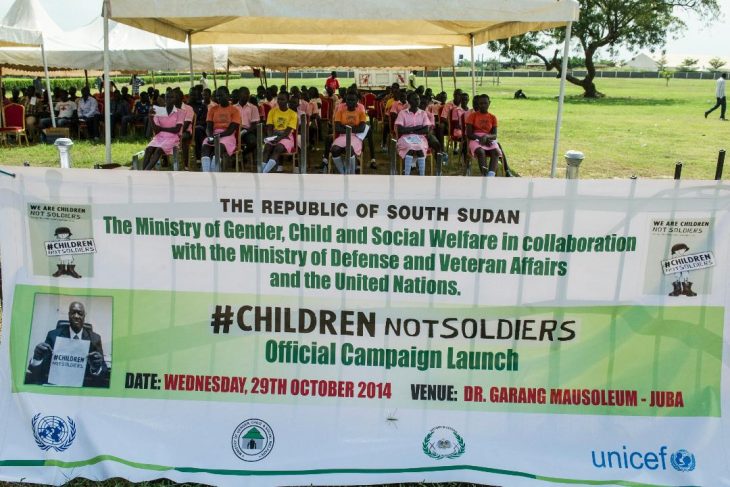

In South Sudan, despite the continuous effort to disarm, demobilize and reintegrate child soldiers, the number of child soldiers has been increasing since the war began in 2013.UNICEF has negotiated the release of nearly 2,000 children. They have been demobilized in the past five years but are still being replaced by other child soldiers. In particular, reintegration is the common challenge mentioned by experts working in the field of DDR in South Sudan.

No family

One of the biggest problems hampering the reintegrating of child soldiers is that many are unable to return to their families. These children have no immediate family left to return to because their families are either dead or displaced. In 2017 Justin, a child solider from a village in Zahra, near Yambio, told Reuter: “I am the only one left. My mother died and my father went to Bentiu, but he didn’t come back. I am only hearing he was killed in the war because he’s a soldier. I don’t want to work in the army (militia) any longer.”

Finding families of former child soldiers can prove almost impossible. Many of these children’s parents are no longer in their villages but in towns and camps for IDPs, and cannot be easily traced. Despite UNICEF’s efforts to reunite families, the spread of violence and current security problems in South Sudan continue to stretch its capacity to respond to the needs of children.

The other challenge encountered in reintegrating child soldiers back in the community is social perceptions. Returnees usually face rejection and stigmatization when the community knows or suspects the child soldiers were involved in raids or killings.

“When I went back home, neighbours point at me and insult me calling me the boy from the bush. Even in class, my class mates don’t want to sit next to me .They think I was a killer, but I did not kill anyone,” said Luka in an interview with UNICEF.

It is troubling to see that stigma is one of the reasons reintegration fails to achieve its goals. Awareness raising within the community is therefore needed to teach that blame should not be attributed to children, since they were forcibly recruited, and the community should help facilitate their smooth return to civilian life.

Poverty and mental health

Furthermore, most child soldiers in South Sudan come from poor communities, and conflict mostly increases poverty. Ex-soldiers’ families are often not ready to support them after they return. In an interview conducted by the Guardian in 2017, David recounted that he was released by rebel groups but rejoined them three months later. “I had nothing once I left the militia,” he said, “no food, no job, no school. I had no choice.” Many young boys like David unable to sustain their economic needs rejoin armed groups. Unless these challenges are addressed through economic reintegration assistance, such as vocational skills training, it will remain a challenge for the reintegration process.

Child soldiers, both as a victims and perpetrators, have experienced and committed violence. This causes severe traumatic stress and deteriorating effects on mental health, such as the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Psychological and physical trauma from violence and family separation remains one of the biggest difficulties when working on transitioning former child soldiers into civilian life.

Researchers such as Elisabeth Schauer and Thomas Elbert state that former child soldiers have difficulties controlling aggressive impulses and have little skill handling life without violence. Unicef in South Sudan say many of these children show ongoing aggressiveness within their families and communities, even after relocation to their home villages. Because of this, some have left their home after reintegration and ended up on the streets, whilst others have rejoined the militias.

Researcher Anne Njuguna adds that most child soldiers in South Sudan suffer from a sense of guilt when they realize the atrocities they committed. It is very common to find that they have difficulties building relationships with others, following rules, concentrating in class or staying motivated. She adds that former child soldiers find it difficult to break their habits and adjust to a new way of life, i.e from military to civilian life. Especially those who spent most of their childhood in combat have no point of reference in this new life, and struggle to determine their new identities. This leaves them feeling lost and abandoned when they are demobilized, creating another huge challenge for the reintegration process.

Lastly, the process and strategies for reintegration of child soldiers require sustained funding and political will from the government, which has not been the case in South Sudan. The fragile security situation threatens to undermine the reintegration of child soldiers. Areas not controlled by the government have no active implementation of the reintegration programme for children. Primary responsibility therefore rests with the government to ensure security, funding and successful reintegration of these children.