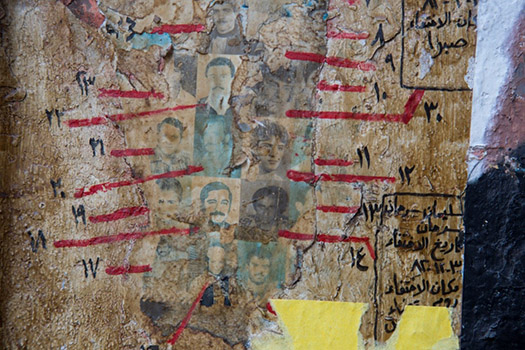

Life continues to stand still for the many families of the missing and disappeared in Lebanon who have been desperately trying to uncover the fate of their loved ones and who are holding out hope of seeing them someday. The Lebanese War ended 28 years ago, but for these families the war rages on.

During Lebanon’s 15-year civil war, thousands of people went missing or were disappeared without a trace or explanation. Their families have never stopped waiting for answers, answers they fear will never come. The Lebanese government has failed to adequately address the issue of the missing and disappeared due in large part to a post-war amnesty law and a lack of political will. Civil society has resolutely sought to fulfill families’ right to know through a number of invaluable initiatives. But these efforts cannot be considered an alternative to a centrally organized national commission capable of addressing the full scale and complexity of this issue—the responsibility for facilitating such a commission falls on state authorities.

A recent legislative breakthrough, however, might finally pave the way for Lebanon to confront its legacy of missing and forcibly disappeared persons. On May 9, the Administrative and Justice Parliamentary Committee passed the Draft Law for the Missing and Forcibly Disappeared, which was submitted to the parliament in 2014 and was drafted by organizations associated with families of the missing with input from ICTJ and other stakeholders.

The key feature of this law is the establishment of an independent national commission charged with discovering the fate of missing and forcibly disappeared persons in Lebanon. Creating this commission would constitute a major step toward fulfilling families’ right to know, as recognized in international law and by Lebanese courts.

The draft law will finally be discussed and voted upon in a plenary session of the newly elected parliament. Before the parliamentary elections in early May, several members of parliament and political parties signed the national petition to disclose the fate of the missing and forcibly disappeared. In doing so, they made a commitment to put an end to the families’ pain, which will hopefully be reflected in their parliamentary votes in favor of the law.

While it is true that today Lebanon is closer than ever before to passing legislation that would establish an independent commission, it is important to bear in mind that adopting the law in and of itself is not sufficient. The law also needs to be effectively implemented and enforced.

In October 2016, for instance, parliament passed a law establishing the National Human Rights Institute, which was considered a positive step toward advancing human rights. After a delay of over a year, the core members of the institute were appointed, but an ongoing lack of funding casts doubt on whether the body can actually begin its mandate and function. Therefore, passing the draft law will be meaningless unless the government demonstrates a greater commitment to addressing the issue of the missing and disappeared and the families’ right to the truth and unless it takes the necessary actions to enforce the law. These actions include expediting the establishment of the commission and providing the necessary resources for the commission to carry out its mandate effectively, impartially, and free of political interference.

Lebanon’s current draft law could lay the groundwork for transitional justice initiatives in Syria as well. It could prove to be a useful template for the discussions about the right to know in a context where the number of the missing and disappeared persons continues to grow. Since the onset of the Syrian crisis in 2011, this number has risen every day.

Building the foundation to meaningfully confront the issue of the missing and disappeared should start as soon as possible. With each passing year, the risk of losing important data increases and identifying the fate of the missing becomes harder.

Syria can learn from Lebanon’s false starts and from previous mechanisms set up by successive Lebanese governments that failed because they lacked many fundamental features such as independence, transparency, accountability, and financial security. Lebanon’s experience demonstrates the need for an independent commission to investigate cases of missing and disappeared persons and deliver the truth to their relatives. Today, the focus in Syria should include gathering, organizing, and documenting information about missing and disappeared persons, a preliminary step that can prepare the way for the necessary processes to search out these individuals once the conditions in Syria are sufficiently stable.

The Lebanese experience proves that, if a society does not swiftly tend to the wounds inflicted by war, those wounds will not heal for generations and will constitute a major obstacle to peace and reconciliation. Unfortunately, the plight of the families of the missing has so far been largely ignored by the authorities in Lebanon and Syria, and the international community has left the subject off its agenda. Families of the missing continue to endure pain, hardship, and political neglect. Without serious attention and earnest efforts to address their suffering and fulfill their right to justice and truth, these families will remain in limbo and be a constant reminder of an unresolved past.