International criminal courts and tribunals, such as the ICT for Rwanda, are commonly understood within legal scholarship as the primary tool that is utilized after mass human rights violations. This is so not only in addressing impunity, but also in uncovering the truth of what happened and why. Victims play a pivotal role in these processes of justice. However, there are significant limitations in legal collective understandings of the past. In legal transitional justice scholarship, these have received sparse critical investigation.

Legal witnesses and their contribution to tribunals ‘truth’ finding process

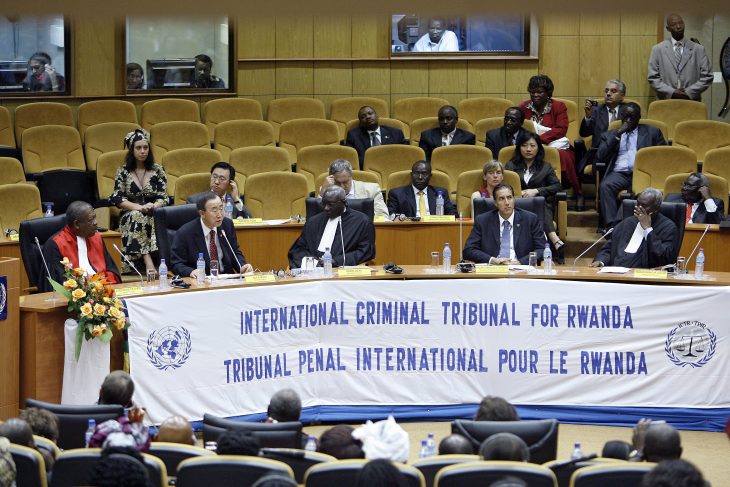

The ICTR (1994-2015), located in Arusha, Tanzania, was tasked to prosecute those responsible for the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. From the outset, this international tribunal had far-reaching ambitions to not only deliver justice but also to aid reconciliation in Rwanda by producing a historical record of how and why the genocide occurred.

![[ICTR & M.N. Kinuthia (2011)]](/images/Cent-jours.png)

Central to the ICTR’s ambitious mandate were the traumatic memories of victims, many of whom had experienced the bloodshed and horrors of the genocide first-hand. It is here, in seeking historical ‘truths’, that a fundamental tension exists in international legal institutions: specifically, between the pursuit of justice and reconciliation, both of which are understood to be essential for successful post-conflict transitions. One of the major reasons for this tension, as I see it, is the historical ‘origins’ of the transitional justice scholarship and practice, which are embedded in the common assumption that international legal and human right norms serve to construct a perception of continuity and consistency in the rule of law during periods of transition. In short, legal norms are a set of ‘western’ legal values that espouse the existence of a standardised framework of criminal law which functions as a universal paradigm for the international community. Saturated with legal norms, international criminal tribunals are often understood as being able to achieve not only legal judgement via a legal determination of guilt or innocence, which is the essence of what a court is there to do, but also contribute to restorative justice, such as ‘recovering’ the ‘truth’. Herein, it is my aim to challenge the legal understanding of witnesses as a self-evident and a fundamental feature of international tribunals’ and courts’ contribution to historical ‘truth’.

Firstly, the kind of truth that legal trials can reach is very different to the kinds of truth survivors, victim’s families and the society effected often want. For example, the importance of victims and their role to international criminal institutions in contributing to both, justice and reconciliation is a key component of the ICC’s (2002- ) victim-oriented approach. According to the ICC chief prosecutor, legal trials can play an important role for victims by offering them a platform to tell the truth about their experiences of a traumatic past. Yet, the kind of historical ‘truth’ which can be told through legal proceedings serves a very specific legal purpose - contributing to the legal determination of guilt or innocence. What victims can say in international trials is tightly controlled and orchestrated. Prosecution and defense counsels ask a predetermined set of questions which contributes, explicitly, towards a legal judgment being reached. Also, prosecutors choose a fraction of the available victims to testify, leaving many people without a chance to tell their story.

![[Artist impression of ICTR]](/images/Arusha.jpg)

The primacy of human rights within the legal transitional justice scholarship indicates that legal norms are crucial to legal understandings of justice and reconciliation at international tribunals. From a human rights perspective, legal witnessing is situated within the wider human rights project. At the core of this project is the understanding that human rights define the highest realm of shared moral values for all humanity. In the context of this article it is specifically related to the ‘Right to Truth’. For human rights advocates, what legal witnesses are is self-evident, and a fundamental feature of international legal responses to mass atrocities. This places a strong emphasis on the importance of criminal tribunals and courts remembering human rights violations. Furthermore, the human rights discourse perceives victims’ testimonies at trials as being a human right in itself. The ‘Right to Truth’ does not only include the right to hear the truth but also the right to impart the truth, which is often framed by advocates of the right within the judicial process of witness testimony. However, human rights discourse on witness memories fails to comprehend the contingent nature of the legal story tribunals produce. The construction of the legal story of past violations is comprised of fragments of individual and collective memories by legal counsels in order to tell a specific narrative to contribute to a legal judgment. The partial and fragmented nature of witness memories is directly at odds with the universality of human rights discourse. Academics and practitioners engaged with the human rights discourse on ‘Right to Truth’ often participate in both analysis of the process of legal witnessing and advocacy for this process. Crucially, this awkward coexistence of analysis and advocacy often leads to ‘faith-based’, rather than ‘fact-based’ prescriptions.

Spaces of legal memory construction

Scholars, such as Mark Osiel, emphasise the collective benefits of legal witnessing by stating that witness testimonies can construct a coherent collective memory of atrocities. This provides victims and affected societies with a collective narrative of past events. However, Osiel’s advocacy for a collective legal narrative of the past negates the contingent nature of memory, and importantly, the central role played by international legal institutions and actors. The construction of memory is understood here as something that is plural, multidimensional and transient, and it is for this reason that I challenge the claim that international criminal tribunals and courts are able to produce a collective memoryof atrocities. The main contention in the literature is that memory is a ‘thing’ which can be recovered through witness testimony in trials and that these accounts will reveal previously ‘hidden’ aspects of the past, contributing to a legal collective understanding of atrocities. Specifically, transitional justice legal scholarship has largely neglected to address the way that international legal institutions and the actors embedded in those – judges, legal counsels, registrars, investigators – can play a fundamental role in the construction of the past in the present. Thus, it is necessary to understand the construction of memory as amultidirectional process. Significantly, to specify agency is vital as it prioritises answering the central questions on the (legal) construction of memory: who remembers, when, why and how?

Notwithstanding the benefits of international criminal proceedings, I propose here that there is a need for the legal transitional justice scholarship to critically engage with international legal institutions as spaces of legal memory construction, specificallychallenging the assumption that these institutions can and should produce a collective legal story of how and why the atrocities occurred. The ICTR is a crucial, albeit neglected, part of the post-conflict memory-scape.

The ICTR archives: a site for exploring the legal construction of mass human rights violations

The ‘legacy debate’ surrounding the contribution of international criminal tribunal archives is construed as providing a historical legal record of the atrocities committed. Such historical records often orientate around a linear constructed narrative of mass violence, which can condense the complexity of past violations into an overly simplified account of past and present. Importantly, there has been little critical engagement by the transitional justice scholarship with legal archives. I challenge the perception that transitional justice archives as passive repositories of history (ICTR 2015). Importantly, I understand legal archives as a site where the judicial conditions that restrict which witnesses can speak and what they can talk about can be explored.

![[The new MICT facility which included the ICTR archives Arusha, Tanzania]](/images/Tanzanie.jpg)

In my doctoral thesis I conduct a conceptual enquiry into witnessing and memory, in which I analyse legal documents from the ICTR archive relating to the selection of witnesses, via engaging with conceptual insights from French philosopher Michel Foucault. It is Foucault’s theoretical insights on discourse that is of interest. Like Foucault, I understand discourse to be where meaning and knowledge about the world is produced through speaking and writing. Specifically, I use Foucault’s insights on the contingent nature of knowledge and subjects (identity) to conduct a discourse analysis of archived ICTR documents. Thus, using Foucault’s insights, I suggest, provides a useful lens through which to explore the legal construction of past atrocities at international tribunals and courts. Therefore, with trials at the ICC and on-going conflicts in the Middle East and Myanmar, which some scholars argue should include trials at The Hague, difficult decisions will need to be made about what combination of justice, ‘truth’, and reconciliation is required during transition. It is thus necessary to critically engage with how international legal institutions and international actors play a central role in the construction of the past in the present. This is crucial in order to gain a fuller understanding of the scope, and limitations, that international legal institutions can have in contributing to the reconstruction of deeply divided societies.