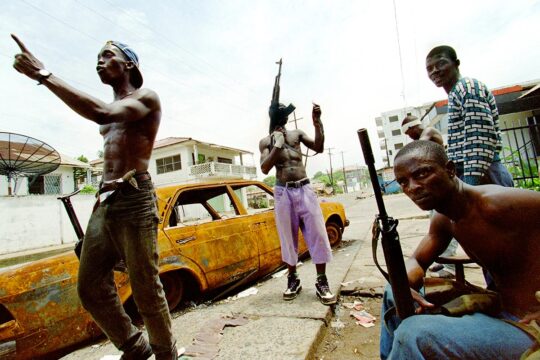

The identity of Kunti K., arrested on September 4 in the Paris suburb of Bobigny, has not yet been revealed. But the allegations against this former Liberian commander are as serious as they are many. He was a member of ULIMO, one of the main factions in the first Liberian civil war of 1989-1996, and is charged with torture and crimes against humanity, including murder, cannibalism, enslavement and using child soldiers. These alleged crimes were committed between 1993, when the suspect was only 19 years old, and 1997.

The investigators clearly had to act fast for fear that the suspect would again skip country. Kunti K., who obtained Dutch nationality, left the Netherlands for Belgium in 2016, according to Colonel Eric Emeraux of the French international crimes unit.

Kunti K.’s case can be compared to that of Alieu Kosiah, another commander of ULIMO from 1993 to1995, who has been detained in Switzerland for nearly four years and whose trial is still awaited. According to judicial sources it was moreover on an urgent request from Swiss judicial authorities that the French authorities started looking for Kunti K. And it was on the basis of a complaint filed in France on July 23 by Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima that French prosecutors took up the case.

A victory for NGOs

This arrest looks primarily like a victory for Civitas Maxima and its Liberian partner, the Global Justice and Research Project (GJRP), a victims’ organization based in Monrovia. “For us and our partners in Liberia and Sierra Leone, this is the sixth arrest we have obtained in five different countries since 2014,” Civitas Maxima director Alain Werner told JusticeInfo. “That is thanks to the Liberian victims who are keeping up the pressure on us. There is a real will to obtain justice wherever they can.”

For the moment, that is in Europe and the United States.

As well as the arrests of Kunti K. in France and Kosiah in Switzerland, complaints filed by Civitas were behind the arrest in Belgium of Martina Johnson, a former artillery commander in ex-president Charles Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL), and Taylor’s former wife Agnes who is being prosecuted for torture in the United Kingdom. Another suspect, Belgian-American businessman Michel Desaedeleer who was detained in Spain in 2015, died in jail in Belgium a year later.

The American campaign

The offensive has also been taking place on US soil. There suspects are not being prosecuted for war crimes in Liberia but for violating US immigration rules by lying about their role in the civil wars. In Philadelphia, however, the court took the opportunity to raise war crimes allegations even if it couldn’t convict on the basis of them. From June 11 to July 3, Charles Taylor’s former spokesman Thomas Woewiyu had to listen to victims brought from Liberia by the prosecutor tell of the atrocities committed during the attack on Monrovia by Taylor’s forces in 1992. Woewiyu could now face up to 110 years in jail. Before him on April 19 Mohammed Jabbateh, alias “Jungle Jabbah”, was sentenced to 30 years for obtaining American citizenship by hiding his past. In that case too, the GJRP helped bring 17 witnesses who testified to sexual violence, forced labour, murder and cannibalism ordered by Jabbateh. These testimonies clearly weighed heavily in the court’s sentencing decision.

Another Liberian, Moses Thomas, is awaiting trial in Philadelphia for immigration fraud. But he is also suspected of involvement in a terrible massacre at the Saint Peter Lutheran church in Monrovia in July 1990 when around 600 people were murdered. He is said to have commanded a special anti-terrorist unit loyal to then-president Samuel Doe and is considered responsible for the massacre.

Objective Monrovia

Ignored by the 1990s movement to create international tribunals and expecting nothing of the International Criminal Court which can only try crimes committed after 2002, Liberian victims and NGOs have found a way through these trials in national courts. In Europe, these initiatives depend on the principle of universal jurisdiction which allows national courts to try serious crimes committed by foreigners on foreign soil. Civitas and GJRP have also drawn direct inspiration from the strategy that led to the trial of former Chadian dictator Hissène Habré in Senegal in 2015. There it was the alliance between an international organization, Human Rights Watch, and Chadian victims’ organizations that gave their judicial campaign the tenacity and legitimacy to succeed.

Fifteen years after the end of the civil wars that left some 250,000 people dead in Liberia between 1989 and 2003, the wind of criminal justice has never blown so strongly on the suspected perpetrators of crimes committed. But the NGOs’ aim is now to ensure that justice is delivered in the victims’ own country. “Our hope now is that all these cases will allow the vast majority of Liberians to obtain justice in Liberia,” explains Alain Werner of Civitas.

That battle is not yet won, but there is mounting pressure on new Liberian president George Weah to implement one of the key recommendations in 2009 of the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which is the creation of a special war crimes chamber. The Commission’s report named more than 100 individuals as suspects, of whom some like warlords George Boley and Prince Johnson are still sitting in parliament. On May 8 this year a group of associations filed a petition to parliament calling for the war crimes court. At the end of July, the UN human rights committee denounced the impunity accorded to Liberian war criminals. People are hoping that the former football champion turned president will remember what he said as a UNICEF ambassador in 2004: “Those who armed children and committed other atrocious crimes against them should be brought to justice.”