What kind of justice should there be for suspected perpetrators of terrorist acts? On January 10 the trial opened in Brussels of Medhi Nemmouche, suspect in the 2014 attack on the Brussels Jewish museum which killed four people. This trial is taking place according to the rules of Belgian criminal law, including the fundamental principle of equal rights for the prosecution and defence. On the other hand, those people imprisoned by the American authorities in Guantanamo for terrorism are experiencing a very different kind of justice, where the basic rights of the defence are violated.

This is what emerges from an article jointly written by Mitch Robinson, who was until recently one of the lawyers in the trial (still ongoing) at Guantanamo of suspects in the September 11 attacks, and Sharon Weill, Senior Lecturer at SciencesPo Paris, who interviewed many of the people working in this very particular justice system.

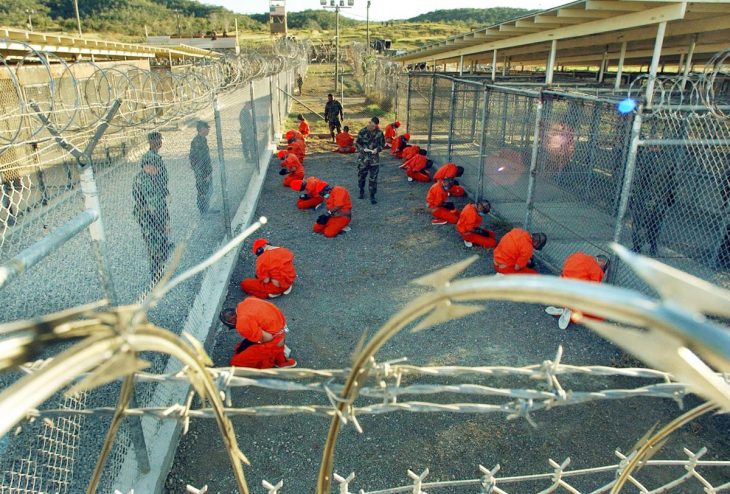

780 prisoners, few trials

The analysis is sober, the tone of the article meticulous, but the reading of “Plongée au cœur des procès pénaux de Guantanamo” (into the heart of the Guantanamo trials), published in Cahiers de la justice of the second half of 2018, is all the more stunning. One would think that suspects in the most spectacular attacks ever carried out -- those of September 11, 2001, which killed some 3,000 people in the United States -- would give rise to a trial that was both public and exemplary. That is not the case. Instead, we discover the quasi-secret functioning of a military justice system that tries to maintain the appearance of operating normally, when it is not at all. On reading this article, we see the emergence of a judicial monstrosity where detainees are tortured, lawyers are spied on and prosecution files are redacted, including for judges, in the name of a wide definition of state secrecy.

The first surprise is to learn that of the 780 suspects jailed in Guantanamo, only a tiny minority have been brought to trial. So far only eight trials have been completed and four others – including five people accused in connection with September 11 – are still under way. Another strange thing is that the CIA can decide to block courtroom viewing for members of the public attending (separated from the courtroom by glass), without the judge even knowing (!), note the authors of the article.

Torture and state secrecy

As for extracting confessions through torture, which is theoretically banned in a democratic state and considered inadmissible as evidence, Weill and Robinson say this does not seem to pose much of a problem at Guantanamo Bay.

The Bush administration considered that confessions by torture are admissible if "the circumstances in which the statement was made make it a reliable element with a sufficient probity value" and that it serves "the interests of justice". The Obama administration limited - somewhat - this provision in 2009, since it prohibited confessions "obtained under torture" but accepted "those derived from torture", which led Weill and Robinson to say that "the difference [in approach between the two administrations] is only marginal". The Trump administration has not yet intervened on this point.

The defence lawyers are themselves under surveillance. It is only after an obstacle course, say the article’s authors, that they can hope to get security clearance allowing them to visit their client and examine essential documents. But the lawyers, who live in the US (they must also be of US nationality), can only meet their clients occasionally and are themselves subject to surveillance. Even the judges – and so of course also the defence lawyers – do not have access to all the pieces of prosecution evidence deemed “state secret”. “The accused are not allowed to come to court when the hearings are about evidence deemed state secret, even if it concerns torture that they themselves have suffered,” say Sharon Weill and Mitch Robinson.

An untenable contradiction

The two authors conclude that the authorities have created a judicial monster, a “Frankenstein that has taken control of everything else”. Their analysis shows the fundamental contradiction at Guantanamo: on the one hand the pitiless war being waged by the US security apparatus with its secret prisons in many countries and use of torture by the CIA; and on the other hand the desire to show the superiority of the US political system with regard to terrorist groups, by holding trials according to rule of law. This contradiction between the means used and the nobility of the goal is untenable. What emerges in the end is an image of judicial proceedings that are totally misguided, irreconcilable with the ideals of American democracy and producing a result that is the opposite of the one sought.