Switzerland is one of the countries that recognizes the principle of universal jurisdiction, allowing it to prosecute any individual suspected of genocide, crimes against humanity or war crimes committed anywhere in the world, provided that person resides on, or is present at some point on Swiss territory. The 2011 law that enshrined universal jurisdiction was hailed by NGOs and civil society, hoping it can help bring justice for victims who cannot get justice in their own country.

Former Liberian rebel leader Alieu Kosiah is one of the two people in custody in a Swiss jail under universal jurisdiction. He has been there for more than four years, suspected of war crimes in his country. The other is former Gambian interior minister Ousman Sonko, arrested in early 2017 and under investigation for crimes against humanity. Both cases were brought to the war crimes unit by Swiss NGOs – Civitas Maxima and TRIAL International respectively.

According to a spokeswoman for the Office of the Attorney General (OAG), in which the international crimes unit is based, more than 60 cases have been referred since 2011, of which most have been dismissed or closed because they failed to “fulfil the contextual requirements laid down by law (e.g. no qualification as a conflict) and/or the requirements for opening proceedings (e.g. perpetrators not in Switzerland)”.

The Algerian case

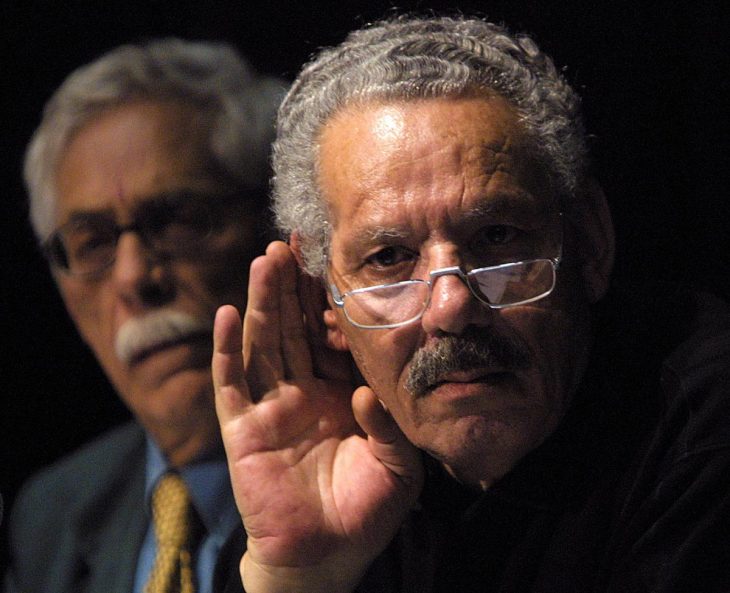

One of the most controversial cases, brought by TRIAL International on behalf of victims, is that of former Algerian Defence Minister Khaled Nezzar. Nezzar was arrested in Switzerland in October 2011 following a criminal denunciation filed by TRIAL over his alleged role in violations committed in the early 1990s in Algeria. He was released after questioning and allowed to return to Algeria on the promise that he would participate in subsequent procedure. The Swiss Attorney General’s office dismissed the case in early 2017, saying there were no grounds to charge Nezzar with war crimes because there was no evidence of an armed conflict in Algeria during the period in question. NGOs were stunned, and the decision was appealed.

“The black decade that Algeria experienced [in the 1990s] left more than 200,000 people dead and there are numerous sources testifying to the intensity of fighting between the Algerian army and armed groups, also to the organization of the armed groups,” TRIAL Legal Advisor Sandra Delval said in 2017. “It is inexplicable that the office of the Attorney General investigated for six years without apparently ever questioning the existence of an armed conflict, only to abruptly close the case saying there was none.”

In April 2018, the UN Special Rapporteurs on Torture and on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers wrote to the Swiss government expressing concern about persistent allegations of political interference particularly in this case, which they said “undermine the independence of the judiciary in the name of interests which appear to be neither those of the rule of law nor of justice”. In a written reply, Swiss Foreign Minister Ignazio Cassis denied all the allegations, saying that “Switzerland attaches great importance to the fight against impunity, especially for crimes falling under international law”.

At the end of May 2018, the Federal Criminal Court overturned the dismissal of the Nezzar case. It ruled that there was indeed an armed conflict in Algeria in the early 1990s, and ordered the Office of the Attorney General to resume the case.

Whatever happens, this case has nevertheless marked case law with a 2012 decision of the Federal Criminal Court refusing to grant Nezzar immunity because of the severity of the crimes in question. This was hailed as a groundbreaking precedent by NGOs.

Lack of means

Prosecutor Laurence Boillat was the first head of the Swiss war crimes unit, which she was instrumental in setting up in 2012. This was an enriching experience, she says, but “we very quickly understood, or were made to understand, that the unit was not going to be very important, because we were only two prosecutors, two judicial staff and one person in charge of the secretariat – so five people, but not even five full-time posts”. “At one time,” she continues, “we had maybe 20 cases, but even with 5 cases in this specialized field, it is ridiculous to imagine that things could be advanced properly with this small team. It’s a shame, because the means were found at the Attorney General’s office for economic crimes, and then for terrorism – but that was a problem too, because staff time was taken from our war crimes unit to tackle terrorism cases.”

Asked about lack of means, the Office of the Attorney General said that the issue was under review but that at the present time it “continues to assume that the means employed in the area of international criminal law are sufficient for the proper performance of its duties”.

Boillat says there was also political pressure from above, especially in cases of “politically exposed persons” like Nezzar and Rifaat Al-Assad, the uncle of the current Syrian president, both of which she opened. This was not so for the cases of asylum seekers in Switzerland, she says. At one point she made it clear that she thought “a spanner was being put in the works with regard to certain investigations”. She was subsequently dismissed from the OAG.

Since she left at the end of 2015, the war crimes unit has been merged with the “Mutual Legal Assistance” division of the OAG – a move criticized by NGOs – and other prosecutors have left.

Justice delayed

Everyone agrees that universal jurisdiction cases are complicated. They involve crimes committed elsewhere, often in conflict zones. Witnesses must be found and brought from other countries and/or prosecutors must travel to the country concerned to investigate. It also depends on what cooperation is given by the countries in question. The new Gambian authorities, for example, are cooperating in the Sonko case, but in Kosiah’s case the Liberian authorities are more difficult.

It takes time and resources. But how much time should it take?

Swiss law says that “where an accused is in detention, the proceedings shall be conducted as a matter of urgency”. Kosiah has been in a Swiss jail since November 2014 and Sonko since January 2017. Under Swiss law their provisional detention has to be justified and approved by judicial authorities every three months, and so far it has been, suggesting that the proceedings against them are progressing and that they will be brought to trial sooner or later.

Back in early 2017 Civitas Maxima director Alain Werner said that the Kosiah case, in which his organization is representing victims, was “well advanced” and that he hoped to see it brought to trial in 2018. Two years have passed and that still has not happened. As Benedict De Moerloose of TRIAL International told JusticeInfo back in 2015, Switzerland has the legal tools in place to be a model in the field of universal jurisdiction cases, but it still has to prove its will and capacity to do so.