The process of memory, truth and justice on crimes against humanity committed in Argentina during the military dictatorship (1976-1983) is one of the most active and remarkable in Latin America and beyond. It may even be considered the “birthplace” of contemporary transitional justice. On December 11, 2018, another significant verdict was issued in an Argentine court. It addressed the responsibility of business officials in human rights violations carried out under the dictatorship.

The process of memory, truth and justice on crimes against humanity committed in Argentina during the dictatorship is one of the most active and remarkable. It may even be considered the “birthplace” of contemporary transitional justice.

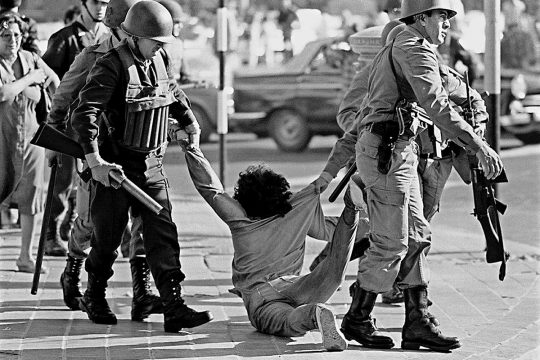

The reckoning of the crimes perpetrated by those in power in Argentina started with the report issued by the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP) in 1984, entitled “Nunca Más”, and the so-called “Trial of the Military Juntas” in 1985. This process included times of impunity, achieved first by laws restricting the legal process during the 1980s, and later by means of presidential executive pardons issued by President Carlos Menem between 1989 and 1990. However, the process regained strength in 2001 when there was a judiciary decision reopening the trials, backed by the Legislative Power in 2003 and the Supreme Court of Justice in 2005. Since then, criminal trials prosecuting those responsible for thousands of forced disappearances, murders, torture and illegal detention began to take place throughout the country. As of September 2018, according to official information, these trials for human rights violations had 862 perpetrators convicted and 122 acquitted. Over half of the convicted are under house arrest.

A 15-year legal battle

Since the end of the dictatorship, researchers, activists and lawyers collected strong evidence showing that several factories had been territories of labor repression and proving that workers, labor leaders and shop-stewards had been primary targets of repression, with military and business participation. When the judiciary process reopened after the turn of the century, one of the issues under scrutiny was the level of responsibility of corporations and business executives in human rights violations. Among many other academic studies, a book published in 2015 by the Latin-American School for Social Sciences (FLACSO), the Center for legal and social studies (CELS) and two offices of the National Ministry of Justice and Human Rights analyzed 25 cases of companies directly involved in human rights violations, many of which were already under investigation in legal processes.

A particularly important case was labelled “Muller, Pedro And Others Concerning Illegal Arrest.” It became known as the “Ford” case, and sought to determine the responsibility of a military leader and of Ford Motor Argentina’s executives in the kidnapping, torture and illegal detention of 24 former Ford workers (some of them also trade union representatives) between 1976 and 1977. This judiciary process started in 2002. It derived from an investigation focused on military chief Santiago Omar Riveros, who was between 1976 and 1978 in charge of the defense zone ‘Campo de Mayo’ where the Ford plant is located. Since 2002, victims and their families have constantly demanded justice in every forum and instance they could find. The “Ford” case was investigated in three different departments of the federal justice system, and took over eleven years to get to trial stage. In 2014 the case was assigned to Federal Oral Court N.1 in San Martin (Province of Buenos Aires) and the trial finally began on December 19, 2017. Three plaintiffs participated in the debate: the Human Rights Secretariat at the national level, that of the Province of Buenos Aires, and the victims.

Four company executives had allegedly been involved in the events. Among them, the former president of the company, Juan María Nicolás Enrique Julián Courard, could not be prosecuted because he had died in 1989, as well as the Manager of Labor Relations Guillermo Galarraga who died in 2016, before the oral proceedings began. Only two executives stood trial: Pedro Müller, manager of production of the plant, who acted as President in Courard´s absence, and Héctor Francisco Jesús Sibilla, who was the Chief of Security at the time.

Corporate participation

The public hearings included the testimonies of the surviving victims, those of their families (spouses, some of their children, and other relatives), as well as those of witnesses called by the defense, and expert witnesses (archivists and social scientists). There were also site visits to the two police headquarters where the workers were held prisoner and to the Ford Motor Argentina plant, including the premises that were used as a detention and torture center for some of the kidnapped workers.

After a year of trial hearings, a panel of three judges found the three accused guilty, and gave sentences of 15 years of effective prison (not house arrest) to Santiago Omar Riveros, 12 years to Sibilla and 10 years to Müller. Judges found Sibilla and Müller to be “necessary participants” (partícipes necesarios), which means that their action and contribution was crucial (necessary) for the illegal detention and torture to occur.

Ford executives made lists of workers to be arrested, targeting them due to their trade-union activism, and made available the firm’s premises for torturing the prisoners.

The closing statements of the Prosecution underlined that the criminal acts, which began the same day as the military Junta seized power, on March 24, 1976, can only be understood when taking into account the shared concern by the armed forces and the company’s leadership about trade union activity and the strength of labor organizations at the plant and beyond. They emphasized that the kidnappings between March and August 1976 happened in a context of increasing presence of military personnel inside the Ford plant. Corporate participation was crucial, it said, as Ford executives made lists of workers to be arrested, targeting them due to their trade-union activism, and made available the firm’s premises for torturing the prisoners, and their vehicles for transferring them to police headquarters.

After many of the victims suffered torments within Ford’s premises, they were later transferred to police stations in nearby locations where their illegal detention and torture continued, including in some cases mock executions. Finally, through different presidential decrees, workers were deemed “prisoners dependent upon the National Executive Authority” and transferred to other prison units. Workers’ families received telegrams from Ford Motor Argentina shortly after the detention of their relatives, and while they were captives, demanding victims to show up at the factory. Then, later, they received telegrams advising that workers had been dismissed for failing to show up at work and fulfill their obligations, despite the fact that most of them had been abducted at their working posts on the assembly line.

According to evidence presented at trial, it was during that time, in 1979 and 1980, that Ford Motor Argentina was for the first and last time in its history the second firm in terms of sales in Argentina, after the national oil company YPF.

The power of multinationals

Defense lawyers did not challenge the facts concerning the human rights violations, but they argued that these were the sole responsibility of the armed forces. Disputing different parts of the evidence accumulated against the two accused business executives, they denied the involvement of their clients in any of these crimes. Also, Ford Motor Argentina made no official statement, referring only to a 2007 press release that essentially blamed the military at the time.

The verdict was announced on December 11, 2018 at a venue packed with the victims, their families, important political leaders and trade unionists, and a massive crowd waiting in an adjacent room and in the street. Forty two years after the events and sixteen years after the case was initiated, the judges ruled that the three accused were responsible for these crimes. Their decision had immediate repercussions in the media around the world. This contrasted with the striking silence of important sectors of the mainstream Argentine media, a clear sign of the power multinational corporations like Ford have as sponsors.

This trial finally allowed the voices of workers and their families to be heard in open court, and their painful and courageous stories to be recorded. Their testimonies and a multiplicity of sources analyzed during the trial reminded us that working class struggle and trade union organization was at the center of this historical process and that the repressive policies and human rights violations aimed at disciplining it. It also illuminated that there was, in this case, direct involvement of companies and business executives in the crimes committed during the repressive policies carried out by the military dictatorship. That’s what makes the “Ford” case crucial in the field of human rights, because it underlines that the severe violations perpetrated by the State can also involve other responsibilities, particularly that of business corporations and officials, that need to be acknowledged and prosecuted.

The Argentine judiciary system does not allow the prosecution of companies, so it was only possible to analyze the responsibility of two top business executives. But even within these limits, this case is a step forward in this path, which is essential not only to better understand a particular historical process, but also to deliver justice, give some sense of reparation to the victims, and prevent such patterns of corporate behavior in the future.

VICTORIA BASUALDO

VICTORIA BASUALDO

Victoria Basualdo has a Ph.D in History from Columbia University, New York. She is a researcher at the National Council of Scientific and Technological Research (CONICET) and at FLACSO Argentina, where she coordinates the Program "Labor studies, trade-union movements and industrial organization". She was summoned as "context witness" at the Ford trial, called by the Secretary of Human Rights of the Province of Buenos Aires.