JUSTICEINFO.NET IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

Andreas Schüller

Director of the International Crimes and Accountability Program at the Berlin-based European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR)

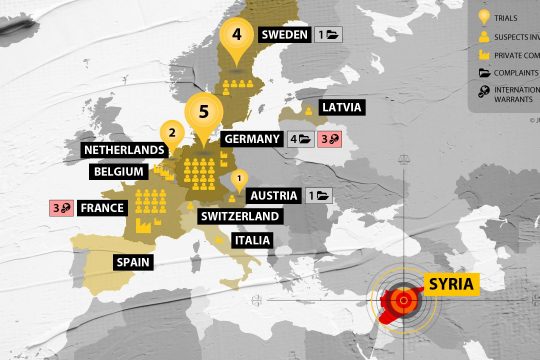

There have been at least 13 trials against individuals charged with crimes committed in Syria in at least 4 European countries in the past three years. There are dozens of cases being investigated or subject to a criminal complaint, a few high-profile international arrest warrants, and significant cases against private companies. Germany is the leading country. Andreas Schüller of the Berlin-based European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR) analyses the current situation.

JUSTICEINFO.NET: How do you see the current effort to use universal jurisdiction in Europe to address crimes committed in Syria?

ANDREAS SCHÜLLER: There are different factors at play. The first is that the ICC [International Criminal Court] is not in a position to act because the United Nations Security Council has blocked any attempt to give it jurisdiction. So at the international level you can only expect very little movement such as the IIIM mechanism [The International, independent and impartial mechanism, established by the UN to gather evidence of crimes committed in Syria]. The same goes with the domestic level, where the Assad regime is still fully in power and not willing to investigate and prosecute those crimes.

This is a situation a bit similar to other conflicts in the past: a deadlock at domestic and international levels. What’s new and positive is that in recent years the justice and accountability debate has often been raised by local actors, victims, affected communities, lawyers, activists who are playing a greater role in articulating their demands compared to 20 years ago.

On Syria, the request for justice and accountability came very early on, at the time of the attacks on protestors in 2011 by the Assad regime. People started to document crimes, there were trainings on how to do this, and many debates on how to get to accountability. As a result, the documentation is pretty strong.

Another factor is that the regime lost some power. There were lots of defectors, a lot of information coming out of the regime – there was no closing of ranks like in other conflicts.

Then in 2015 many Syrians came to Western Europe. And with ISIS, lots of fighters came from Europe before traveling back. That created a close relationship between Western European countries and Syria, and a strong interest in accountability questions.

All of this led to the judicial processes that are going on now.

What kind of cases are being brought? Is there a pattern or is it a mixed picture?

The picture is fragmented, which is normal when it comes to universal jurisdiction cases. The ICC or domestic jurisdictions can take a more holistic approach, whereas many third states are more limited in their case selection. That’s what we see with Syria. On the one hand, we have cases based on opportunity because perpetrators happen to be in one or the other country, and most of these are non-state actors. You have al-Nusra, ISIS, al-Sham and Free Syrian Army cases, different non-state actors who have been part of the conflict and from which suspects happened to be found in Europe. However lately, Germany and France arrested three regime actors suspected of crimes against humanity.

On the one hand, we have cases based on opportunity because perpetrators happen to be in one or the other country. Then you have a more strategic approach with arrest warrants followed by extradition requests

Then you have a more strategic approach, which was requested by Syrian groups and supported by us at ECCHR and others, to build cases against high-level perpetrators, with arrest warrants followed by extradition requests, as last week by Germany to Lebanon regarding air force intelligence chief Jamil Hassan.

This happened in Germany and in France through so called structural investigations, in which all kinds of evidence is secured. Other comprehensive complaints were filed in Austria and now in Sweden.

This describes the landscape of universal jurisdiction with on the one hand a “no safe haven” approach – you prosecute those you find on your territory – and on the other hand what Maximo Langer calls the “global enforcer” approach, a more strategic way of gathering evidence for arrest warrants against high-level perpetrators, like state actors.

Are judicial systems opportunistic and non-judicial actors more strategic?

It depends. Political considerations often play a role in judicial systems as well. By now, there are national war crimes units and prosecutors that are being strategic; they have understood over the years the benefit and the necessity of it, in order to have a certain impact with universal jurisdiction prosecutions. They understand better that the purpose of acting on behalf of the global community is not achieved with just prosecuting whoever happens to be on your territory but rather to look at your case selection.

So this is beginning to happen, but it is pushed by civil society and NGOs, as well as local actors who say: such and such case means more to us than others.

In the case of Syria, prosecutions do not only target combatants. There are a couple of cases against European companies and executives. The most high-profile is the Lafarge case in France. Why is the Lafarge case so important?

If you have a more holistic view of the conflict, if you see who fuels it and profits from it, you immediately look at economic actors and interests. So this has to be addressed. It goes back to the experience of the Nuremberg trials, where you had a number of follow-up trials looking into the role and responsibilities of lawyers or of industrialists.

In Syria, it is important not to see it only from the perspective of sanctions breaches [Syria is under international economic sanctions] but from a complicity in crimes against humanity perspective.

International courts have failed to prosecute businessmen and companies despite claims by a number of international prosecutors that they would do so. At the domestic level we’ve seen courts going after private, mercenary-like businessmen who had profited from conflicts. Lafarge, on the contrary, is a well-established corporation. Is it what makes a significant difference?

It is different to see a well-established company in the dock than a smaller businessman. It’s the first time a case like this focuses on crimes against humanity, and that’s what we pushed for at ECCHR. You also don’t see much European or North American governments in the dock for systematic torture, like the U.S. or the U.K. in Iraq, or for complicity in other grave crimes. It’s what we refer to as double standards in international criminal law. With corporations, it’s a bit similar: these are huge actors, influential in Western states, and the question of double standards is clearly posed. It should always be the aim to also see what is the role of Western actors in a conflict – and you often find such roles.

It is different to see a well-established company in the dock than a smaller businessman. It’s the first time a case like this focuses on crimes against humanity

This is not to say it’s all equally as serious: you have to weigh it up against the systematic torture by the Assad regime. But European companies are doing business in Syria, and you have to look also at what the anti-IS coalition is doing. This has to be addressed while also being put in proper comparison with what the Syrian regime is doing.

Does it reinforce the idea that domestic courts are better suited to prosecute corporate crimes than international tribunals?

International courts are regulated and limited by their statutes, which are often tailored to a particular conflict. So there might be something there that makes it more difficult for prosecutors to go after Western companies. There are budget questions where pressure could be exercised. As regard to the ICC, the Statute is not perfect in terms of going after corporate actors, and indeed the court has quite a number of problems going after non military, state leaders. Corporate crimes are usually a bit more far removed from the crime scenes, with corporate actors then as "secondary perpetrators". There are lots of obstacles.

We hope that the Lafarge case can be an example on how to prosecute these cases, showing that domestic prosecutors do not have to limit their work to crimes relating to breaches of sanctions

We hope that the Lafarge case can be an example on how to prosecute these cases, showing that domestic prosecutors do not have to limit their work to crimes relating to breaches of sanctions, that it is indeed possible to address the other serious forms of criminality that often attach to corporate activity undertaken in the context of armed conflict.

In a number of cases, suspects are charged with terrorism, or membership in a terrorist organization, rather than with war crimes. Human Rights Watch said that this a tendency in all European countries, particularly with regards to the crimes in Syria and Iraq. The argument is that it is easier to prove and quicker. How do you see this tension between terrorism and war crimes charges?

It might be true that it’s easier and quicker. The question is: what do you achieve? What’s the narrative in such a trial - especially with regard to a future transitional justice perspective? What’s the crime about? That’s why we always argue that it’s important to include international crimes and, whenever possible, to call what’s happening by its name.

If an act constitutes a war crime, it needs to be addressed to show the full picture of what has happened. This can’t be achieved in a case that looks only at the crime of membership of a terrorist organization.

If an act constitutes a war crime such as torture, or a crime against humanity, it needs to be addressed to show the full picture of what has happened. This can’t be achieved in a case that looks only at the crime of membership of a terrorist organization. And terrorism charges are laid almost exclusively against non-state actors, although many state actors commit similar crimes.

ECCHR works on the same model as many today, through partnerships with groups of victims or NGOs from the “Global South”. Do you see the evolution from a top-down approach to bottom-up initiatives as a response to a lack of legitimacy of international models?

It is important to go back to the 1970’s and the 1980’s and all those wars and crimes that never came before a tribunal. Was it because of the law? Was it because of the Cold War? When international justice came back in the 1990’s, it was top-down, and we saw how problematic it was in terms of the broader impact of such trials within the affected societies. If you bring in people from the societies where the crimes were committed to shape the narrative, to select the cases, to report back, the legal actions will have a different and better impact in a long term transition.

The Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima has a strategy focusing on one situation: Liberia. They’ve had quite a success with between 5 and 10 former Liberian warlords being prosecuted in the U.S and a number of European countries. Your organization has a much broader spectrum. How do you see the two strategies?

Civitas Maxima is doing great work and the results of its focusing on one country are quite encouraging. They have been more than just lawyers for a group in Liberia; they brought a strategic element and the knowledge they have in terms of how to litigate, how to investigate, how to track people, how to talk to war crimes units. So it’s a very fruitful collaboration.

At ECCHR, the team working on Syria is around the same size as Civitas Maxima. If we see an opportunity for impact we are in the position to invest resources in the long term and focus on a particular conflict over several years.

But strength also comes from understanding developments in international justice globally, what the ICC is doing, what national war crimes units are doing, and having a good sense of where the legislation is going, and see what would be the best approach for a particular group in a particular conflict. To survey the landscape constantly, from various perspectives, continued exchanges and workshops, helps to find these windows of opportunity.

A number of actors are working on crimes in Syria: the IIIM, the Commission for International Justice and Accountability (CIJA), domestic war crimes units, NGOs like yours. How efficient and how coherent is it?

I think it offers opportunities. When there is only one actor, that’s what you focus on and that’s all you have. Syria, in this sense, is very dynamic. You have to react constantly to changes at all levels.

When there is only one actor, that’s what you focus on and that’s all you have. Syria, in this sense, is very dynamic. You have to react constantly to changes at all levels.

In 2012 we were already in a position to act swiftly. The German war crimes unit started to investigate cases in late 2011. And in 2015 when many Syrians came to Germany we were also in a position to react very quickly. At a time when governments’ war crimes units were probably not able to deal with a huge amount of documents coming out of Syria and protect it for future use in prosecutions, CIJA played its role. It is of great use to support investigations that need to be made by state war crimes units in the end, not private prosecutors. Then the IIIM came into play. It’s another dynamic, another development that needs all the support possible.

How do you assess the IIIM?

Its establishment is a big first success and shows that many states will still stand up for justice. It will however take another two or three years to see what the IIIM achieved, how effective it was. You also need to see the IIIM from a long-term perspective: in ten or twenty years, has the evidence collected been used? It makes sense to evaluate every couple of years but we shouldn’t underestimate the long-term impact these investigations can have.

And how efficient are national war crimes units?

There are huge differences. Some war crimes units can’t do their job because they lack jurisdiction. There is some progress with the role of Europol and Eurojust, the EU Genocide network, and joint investigations teams.

In Germany you can say that it is going quite well in the past five to six years; a lot of evidence has been secured; you have arrest warrants and a number of trials already going on; investigators are very knowledgeable.

We need more states with the capacity and legislation and political will to support this at the European level.

But we need more states with the capacity and legislation and political will to support this at the European level. One common feature of the cases is that they are transnational, you have evidence everywhere, you have potential victims and suspects everywhere, so you need cooperation between states to prosecute those cases.

Germany is doing a lot with regards to Syria but it might also have its limits when it comes to other conflicts. The French are quite active on Syria, Sweden as well. The Dutch war crimes unit is active but has jurisdictional limits. Belgium too. Then there’s very little happening in Switzerland, Austria and Spain. So there is room for improvement here, to say nothing of other countries further afield.

On February 1, a U.S. District Court entered default judgment against the Syrian Arab Republic for the targeted assassination of American war correspondent Marie Colvin, as a war crime. How does this trial fit into this effort?

It’s part of the effort. It was a civil case. A lot of documents from CIJA were used, and what the case produced in terms of evidence is really great and is already being used in some of the European universal jurisdiction criminal cases. Furthermore, a court has ruled about who bears legal responsibility for heinous crimes.

Do you see the current enthusiasm for universal jurisdiction as a symptom of the general decline of international models and the crisis of the ICC? Is Syria a telling illustration of this?

We see it as a development. You no longer have the spectacular cases from the 1990’s, like the Pinochets, the Milosevics. It’s more low and mid-level cases. There are some high-level cases that you see in these universal jurisdiction cases but not former heads of state. This shows that certain structures and laws have been put in place over the years. It is complementary to the ICC.

You no longer have the spectacular cases from the 1990’s, like the Pinochets, the Milosevics. It’s more low and mid-level cases.

Of course the ICC has its problems, quite a few, and it has to deal with it, from the quality of investigations to the selection of cases. But national war crimes units and prosecutors have also benefitted from the exchange with ICC prosecutors and other war crimes units.

What did they benefit from?

In Germany, the generation of prosecutors who were in charge of these cases in the 2000’s are not there anymore. Younger ones are now in and they know exactly what they are talking about because in the last twenty years, in their career and in their education, international justice was real, it was happening. This makes a huge difference compared with someone who was never educated in those developments and had just heard about the Nuremberg trials.

There’s a growing community on all levels. The next one would probably be national judges where we still have quite a lack of experience in transnational cases. But there is something now in place that will not go away that easily, even if the ICC still has a lot to do to improve its approach and work.

Would you say that it is less a sign of the decline of international models than the natural evolution of war crimes justice, that it goes back to the national level?

It is a bit difficult with universal jurisdiction cases, because I also think that it is not really natural to have a Syrian case in a German court: it should be in a Syrian court. But as long as this is not possible, it’s the second or third best option.

It would be better to have a holistic view of a conflict, which is lacking in universal jurisdiction cases because many states have this “no safe haven” approach

The establishment of the ICC was important. It has been designed as a court of last resort, so some states understood that they needed to do more. It would be better to have a holistic view of a conflict, which is lacking in universal jurisdiction cases because many states have this “no safe haven” approach, which is a more reactive approach. The ICC had a holistic approach from the start, looking at a particular conflict situation as a whole, but it proved very limited because it did only one or two cases per conflict, if at all.

So I think [the evolution] comes from many directions, but it’s a positive development that it goes back to the domestic level. And again, we are talking about a handful of states, so it is still very limited.

A variety of Syrian warring factions are the target of current cases in Europe. Universal jurisdiction may appear as better equipped to avoid one-sided justice, but what about international responsibilities and that of powerful states?

It is not enough for civil society and human rights organizations to focus only on the politically “easy” cases. They must strive to also bring powerful actors and states to justice for their human rights crimes. In so many cases, there are double standards at play and powerful states avoid being brought to court. Cases of systematic torture from Syria must happen, but so too must cases of torture and prisoner abuse by the U.S. and the U.K. in Guantanamo, in Iraq, and elsewhere. We must look too at what is happening in the name of countering violent extremism in northern Africa, in Yemen and elsewhere, in terms of drone strikes and other abuses by Western states. All this needs to be addressed, documented, investigated. But of course it is much more difficult to achieve this.

To our knowledge, no one from the former Bush administration has ever come to Europe after leaving office. So there are things in place.

One of our cases did lead to a former Guantanamo commander being summoned by a French judge. The U.S. State Department has sent travel warnings to former senior officials in the Bush administration who were involved in setting up the torture program. The CIA has travel warnings out there indicating that certain people shouldn’t travel to certain countries. To our knowledge, no one from the former Bush administration has ever come to Europe after leaving office. So there are things in place. There aren’t big, spectacular cases, but if you address Western crimes over many years, you can also help support U.S. groups to make their claims for accountability at home and for domestic trials.

The military victory of the Assad regime is almost complete now. Have you already observed that it’s closing the window of opportunity for accountability?

Not yet. Most cases are based on evidence that is completely outside the country. So those cases can happen. The question is more: if the regime remains in power, would suspects and people subject to arrest warrants be travelling internationally and what would an extradition procedure look like? Of course it is more unlikely as long as they stay in power and this is the current state. But who knows what it will look like in three years?

There is also the prospect of an important return of European fighters from territories formerly held by ISIS to their respective states of origin. Is there a risk of judicial systems being overwhelmed and asked to deal with their own nationals rather than with the other cases they’ve been working on?

There are already prosecutions of foreign fighters in Germany. Some units work on terrorism-related charges against non-state actors, including ISIS. There are the Yazidi cases going on, genocide cases which we shouldn’t forget. This is all happening. I don’t think it will be overwhelming. States are usually experienced in prosecuting counter-terrorism cases. Of course there is tension with resources. But again it’s more than putting people in jail because they were members of ISIS: you have to address the entire conflict and its context. That is what we hope to see over the coming years.

Interviewed by Thierry Cruvellier.

ANDREAS SCHULLER

ANDREAS SCHULLER

Andreas Schüller, a German lawyer, is the director of the International Crimes and Accountability Program at the Berlin-based European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights (ECCHR), which he joined in 2009. He works on U.S. torture and drone strikes, U.K. torture in Iraq, war crimes in Sri Lanka and Syria as well as other international crimes cases.