Context: (Conflict 1999 – 2011)

After independence from France in 1960, Côte d’Ivoire was governed by Félix Houphouët-Boigny until his death in 1993. He was succeeded by Henri Konan Bédié.

Bédié was overthrown in a military coup by Robert Guei in 1999. Bédié fled to France, the former colonial power with which Côte d’Ivoire has maintained close contacts, notably military cooperation agreements. It was Bédié who introduced the idea of “ivoirité” (a political interpretation of who had a right to Ivorian nationality in a historically pluralistic country).

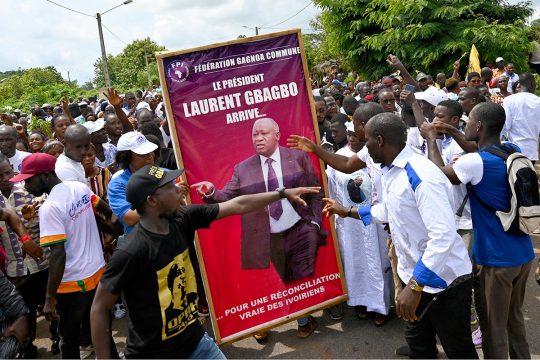

Elections in 2000, officially won by Bédié, were followed by a popular uprising and Guei was replaced as President by Laurent Gbagbo, believed to have been the real winner of the polls.

The roots of the conflict also stem from the exclusion of Alassane Ouattara, a Northerner and former deputy head of the International Monetary Fund, from the 2000 polls on the pretext of “doubtful nationality” (he was born in Côte d’Ivoire although his father came from Burkina Faso).

Fighting erupted in 2000 between southern, mainly Christian forces of Gbagbo and Northern, predominantly Muslim forces of Alassane Ouatarra. Forces loyal to Ouattara seized control of the North, effectively partitioning the country. A French peacekeeping force started deploying in Côte d’Ivoire in September 2002, with a mandate from the UN Security Council. In 2004, UN forces deployed to police a “buffer zone” between North and South, following a fragile peace deal in 2003. In November 2004, nine French soldiers were killed in a government attack on rebel positions in the North, and France retaliated, destroying Ivorian aircraft. The crisis was punctuated by anti-French and anti-UN demonstrations and attacks on the press.

A further peace accord in 2007, mediated by Burkina Faso, led to another power-sharing deal between Gbagbo’s government and Ouattara’s New Forces. Moves followed to dismantle the buffer zone, demobilize rebel fighters and reunite the country. Elections were again postponed in 2008, mainly for security reasons, allowing Gbagbo to stay in power beyond his mandate.

The so-called “second Ivorian Civil War” erupted after December 2010 presidential elections. The electoral commission declared Ouattara the winner, whereas the government-influenced Constitutional Court said Gbagbo had won. Ouattara’s win was endorsed by the international community. However, Gbagbo refused to accept defeat and widespread violence ensued, leading to the deaths of some 3,000 people. In April 2011, Gbagbo was captured with the help of the French army, and Ouattara was inaugurated as President. Gbagbo was transferred to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in November 2011 to face charges of crimes against humanity.

In June 2011, Ouattara created a National Commission of Inquiry, a Special Investigative Cell, and a Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission to respond to the abuses committed during the post-election crisis. In August 2012, the National Commission of Inquiry released a summary of its report, which confirmed that serious crimes had been committed by pro-Gbagbo and pro-Ouattara forces, and recommended bringing those responsible for abuses to justice. These findings echoed a UN-mandated international commission of inquiry and reports by human rights groups. However, only people who were close to Gabgbo during the conflict have so far been prosecuted, despite repeated promises of impartial justice by both Ouattara and the ICC.

Tansitional Justice Mechanisms

International Criminal Court: There are currently three cases relating to Côte d’Ivoire before the ICC, with two people in detention awaiting trial: former President Laurent Gbagbo and former Youth Minister Charles Blé-Goudé. They were both transferred to the Court by Côte d’Ivoire. On March 11, 2015, an ICC court agreed to a prosecutor’s request to join the trials of Gbagbo and Blé-Goudé, saying that “both Mr Gbagbo and Mr Blé Goudé have had charges confirmed against them which arise from the same allegations, namely crimes allegedly committed during the same four incidents by the same direct perpetrators who targeted the same victims because they were perceived to be supporters of Alassane Ouattara”.

The ICC is also seeking the transfer of Gbagbo’s wife Simone, the former First Lady, but Côte d’Ivoire has so far refused to hand her over. The ICC has been criticized for so far pursuing only people on Gbagbo’s side during the conflict, whereas figures close to current President Alassane Ouattara are also suspected of having committed serious crimes. “The ICC has not pursued anyone from the forces that fought for President Ouattara,” Human Rights Watch said in September 2014, “despite findings by both international and Ivorian commissions of inquiry that both sides committed war crimes and possible crimes against humanity.”

Ex-president Gbagbo was transferred to the ICC on November 30, 2011. He is charged with four crimes against humanity (murder, rape, other inhumane acts or – in the alternative – attempted murder, and persecution) in connection with post-election violence in Côte d’Ivoire in 2010 and 2011. The charges were confirmed on June 12, 2014. Gbagbo is accused of individual responsibility for these crimes, committed jointly with members of his inner circle and members of forces that supported him. He is to go on trial with Blé Goudé. Gbagbo will be the first ex-president to be tried by the ICC.

Former Youth Minister Blé-Goudé was transferred to the ICC on March 22, 2014. He is charged with four crimes against humanity (murder, rape, other inhumane acts or – in the alternative – attempted murder, and persecution) committed in Abidjan between December 16, 2010 and on or around April 12, 2011. Charges against him were confirmed on December 11, 2014. The prosecution claimed during the hearing that he “mobilized and manipulated” a whole generation of youth in his country, giving quasi-military orders to a youth army. He will be tried with Gbagbo.

Former First Lady Simone Gbagbo is also wanted by the ICC, which unveiled an arrest warrant against her on November 22, 2012. She is suspected of crimes against humanity (murder, rape and other sexual violence, persecution and other inhuman acts), committed during the 2010-2011 post-electoral violence in Côte d'Ivoire. Abidjan has so far refused to hand her over, and filed a request to the ICC to try her in a national court. In December 2014, the ICC rejected this request and reminded Abidjan of its obligation to transfer Simone Gbagbo “without delay”. This has not so far happened. Instead, she was put on trial in Abidjan and sentenced to 20 years in jail (see below).

National Trials

On March 10, a court in Abidjan sentenced former First Lady Simone Gbagbo to 20 years in jail for “undermining state security, participating in an insurrectional movement and disturbing public order”. Many see the sentence as too harsh, especially since the prosecutor had only asked for ten years. Simone and 78 others formerly close to her husband Laurent Gbagbo were tried for their role in the 2010-2011 post-election crisis. The high profile trial began in December 2014.

Pascal Affi N'Guessan, the contested head of the Ivorian Popular Front (Front populaire ivoirien, FPI, Laurent Gbagbo’s party) got an 18-month suspended sentence, which is covered by the two years he already spent in provisional detention. Michel Gbagbo, son of former president Gbagbo from a previous marriage with a Frenchwoman, was sentenced to five years in jail.

Other pro-Gabgbo individuals have also been charged but not yet brought to trial. Many are languishing in pre-trial detention, according to human rights groups. In January 2015, some fifty Ivoirian senior officials who served under Gbagbo and had been detained for their role in the 2010-2011 post-election crisis were granted interim release. A statement signed by General Prosecutor Christophe Richard Adou said that the bank accounts of some thirty pro-Gbagbo politicians had also been unfrozen.

No-one from the Ouattara side of the conflict has so far been charged, despite promises by the current president of impartial justice. Speaking to the press in January 2015, he promised that every case would be brought to court. “The National Commission of Inquiry has drawn up a list of suspects,” Ouattara said. “These people will be brought before the courts. They will have to answer for their alleged acts.” He suggested that they could be given amnesty after their trial. “Once the judgments have been handed down, the Head of State clearly has some prerogatives to propose pardon and amnesty measures to the National Assembly,” Ouattara told the press.

Dialogue, Truth, and Reconciliation Commission

Shortly after the crisis, the new government of President Alassane Ouattara announced the establishment of a Dialogue, Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Commission Dialogue, Vérité et Réconciliation, CDVR) to investigate past human rights violations and promote national reconciliation. The 11-member Commission, chaired by former Prime Minister Charles Konan Banny, was inaugurated in September 2011 with an initial two-year mandate. It produced a preliminary report in November 2013, focusing on the causes of the conflict, but without holding any public hearings. Its mandate was renewed for a further year and it finally held three weeks of public hearings in September 2014, with testimonies of 80 people, including victims and perpetrators. The Commission submitted a final report to the government in December 2014.

The Commission has been widely criticized by local civil society and victims’ groups, and by NGOs. The 80 public testimonies represented only a fraction of some 70,000 witness statements received by the Commission. Media coverage was also restricted. “The lack of television broadcasts from the commission and low key media coverage meant that powerful witness statements had little impact across the country,” says the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ). “That raised questions over whether the commission could meet its goals of healing the national trauma.”

The Commission has also been criticized for having a politician at its head. Presenting the Commission’s final report to the government, chairman Konan Banny said its proposals include introducing national days of remembrance and forgiveness, and “national dialogue” days. But he said this would serve no purpose unless judicial proceedings were speeded up against suspected perpetrators of the most serious crimes. The Commission is also urging the release of detainees not considered a danger to society, which the government says it is already doing. According to the government website, President Ouattara instructed the government to “examine the present report and implement the recommendations deemed pertinent to complete this process”. He also announced the allocation of a 10 billion CFA franc ($17 million) budget for victim reparations as of 2015.