There are not many people in the courtroom this Thursday March 21 at the Tunis Court of First Instance where the transitional justice chamber is sitting. Yet today's trial is emblematic of the security obsession of former President Ben Ali, who was in power between 1987 and 2011. At the beginning of the 1990s, his paranoia wreaked havoc on the Tunisian army. This is the third hearing in the case, in which 140 victims are represented, mostly senior officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers. The lives of these people and their families became a nightmare just because of the president’s suspicion.

Manipulation and lies

In May 1991, 244 soldiers were arrested and charged with an attempted coup d'état. According to the authorities, they met in the village of Barraket Essahel, near Hammamet, in January 1991 to devise their plot. The army members were handed over by their superiors to the Interior Ministry and tortured in its jails by State security agents. A press conference organized by the Minister of the Interior finally convinced the public that there had been a coup plot. In 1992, 93 judgments were handed down, resulting in sentences of 18 months to 16 years' imprisonment.

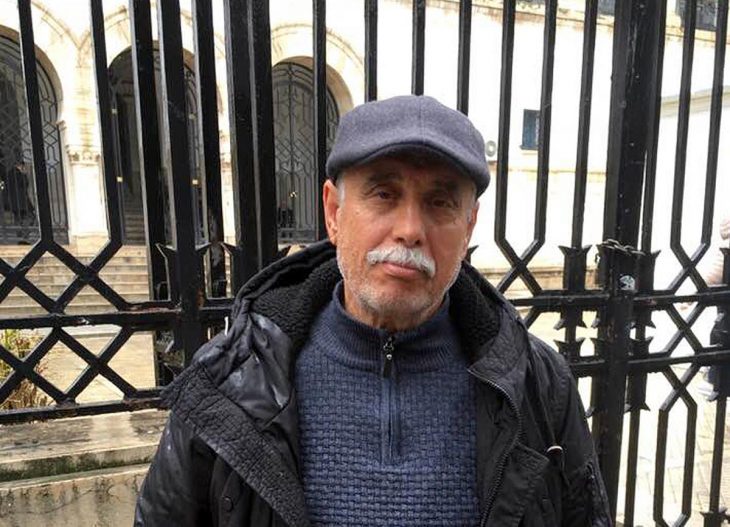

Colonel Major Hedi Kolsi, who chaired the INSAF association (Justice for Former Military Personnel) until 2018, looked back at this tragedy caused by a state lie that lasted 20 years, up to the Revolution in January 2011. "All military personnel, even those released, were dismissed and stripped of their military ranking. Ben Ali's apology through his then Minister of the Interior, Abdallah Kallel, to some 20 senior officers did not change their situation. They will never return to their units again," explained the Colonel Major.

"I was handcuffed and treated like a criminal"

Hedi Kolsi and his friend Colonel Mohsen Mighri, current president of INSAF, told of twenty years of administrative control, police harassment, poverty, and being banned from travel or being treated in public hospitals. At 35 and 37 years of age, they both found themselves in a situation of forced early retirement. Their children were not spared from reprisals by the regime: they were unable to access public universities or work in state-owned companies.

The other victims tell the same story. Fethi Chtioui was a sergeant major in 1991. His bosses seemed satisfied with his seriousness and hard work. When he was arrested on his way home, no one explained the reasons for his arrest. "I was handcuffed and treated like a criminal, Your Honour," he told the judge in a voice affected by widespread cancer.

As a vigorous young man at the time, he was the main provider for his family, especially his elderly parents. At the Ministry of the Interior, he was asked about names he knew well because they were his colleagues. However, he knew nothing about the supposed plot on which they questioned him. This stirred the anger of his interrogators and led to the worst forms of abuse against him, including introduction of an object into his anus. Considered an outcast in his region, Fethi Chtioui was forced to work on construction sites as a handyman.

Impact on the families

Warrant Officer Hédi Dkhailiya's wife also testified. Her husband died in a car accident in 1997. Released in 1991 after fifteen days of arbitrary detention and torture, he had kept records of the abuse and malnutrition until his death. "Neither he nor any of the family had access to any administrative documents. Close relatives avoided us for fear of being associated with the charges that stuck to my husband," she says. The mother hid everything about the alleged plot from her children. The daughter only learned the truth after the Revolution, when the case was brought to light again and drew interest from the media which were also freed from the yoke of fear and censorship. "My daughter fell into depression when she learned about the Barraket Essahel case. Despair continues to pursue us, Your Honour," she said, in tears.

The interminable wait

The Court has named 14 accused: President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, his minister Abdallah Kallel, his Director of Military Security Mohamed Farza, his Army Chief Mohamed Hédi Belhassine, his President of the Military Tribunal Mohamed Ben Mohamed Guezguez, his Director of Special Services Mohamed Ali Ganzoui, as well as several torturers from the Ministry of the Interior. According to Hédi Kolsi, the Ministry of Defence and its top officers, including General Moussa Lekhlifi and General Farza, are primarily responsible for this violation because they failed to protect their men.

Over the months, however, public and media interest in this historical injustice has waned. A lawyer for the civil parties regretted this, recalling that "the first hearing, held on 25 October 2018, saw a record attendance, which prompted the judicial authorities to install a giant screen outside the courtroom so that those present in court could hear the victims' testimonies."

Hedi Kolsi also seems sceptical, especially concerning the slow pace of procedures for the officers to recover their rights. This is despite an official apology by President Moncef Marzouki in June 2012 and a law published in 2014 in their favour. In June 2012, the military victims began proceedings with the Ministry of Defence and obtained military care cards, the registration of their status on their identity card, the recovery of their contributions to the army insurance fund and an access card to the messes. But for eight years they have been waiting for their careers to be rebuilt and for the whole truth to be told about the "Barraket Essahel" case.

"The trial is likely to be very long. Out of the 140 victims, the Tunis Specialized Chamber has only heard 20 people so far. When will we ever get justice?" asked Hedi Kolsi.