On March 24, a massive crowd of hundreds of thousands marched in the streets of Buenos Aires, the capital of Argentina, towards Plaza de Mayo to repudiate the coup that seized power forty-three years earlier, on March 24, 1976. Somewhere amidst the immense crowd were the survivors of a particular crime, the kidnapped and tortured workers of Ford Motor Argentina, and their families, surrounded by over 70 trade-union organizations and confederations. They were holding a giant banner stating: “The Ford trial: a workers´ victory.”

Survivors and relatives handed out thousands of leaflets. They were photographed and greeted once and again. And they were mentioned in the main speech which celebrated the importance of the verdict in this particular trial, while being reminded of many other cases and trials, such as the one analyzing the repression in Villa Constitución and of the Steel mill Acindar, as well as the trial about the violations of human rights against Mercedes-Benz workers in Argentina during the military dictatorship.

International jurisprudence

The so-called “Ford trial” began in 2002 and was postponed for years before its final oral proceedings took place between December 2017 and December 2018. The verdict announced by an Argentine court on December 11, 2018 was path-breaking as it sentenced not only Santiago Omar Riveros, a high-ranking military chief, but also Héctor Sibilla, the Ford Motor Argentina Chief of Security and Pedro Müller, the Production Manager of the Ford plant in Pacheco (a suburb of Greater Buenos Aires) to 15, 12 and 10 years in prison respectively. It found the three of them guilty of human rights violations perpetrated between 1976 and 1977 against 24 former Ford workers.

But the judges’ reasoning behind this landmark decision remained to be known. It was released on March 15 and it gave an added dimension to the case. First, the judges Osvaldo A. Facciano, Mario Gambacorta and Eugenio Martínez Ferrero reaffirmed how these acts qualified as crimes against humanity. They not only cited rulings by the Argentine Supreme Court; they also referred to the jurisprudence of several international tribunals, and to the Rome Statute, to clearly affirm that civilians could indeed be perpetrators of such crimes.

A second impressive aspect of the reasoning is the detailed and specific analysis of the ways Ford Motor Argentina officials got involved in the repression. The judges stated that there was, on the part of Ford authorities and top officials, “a specific contribution of information about the workers to be kidnapped”. On the one hand, they handed the military forces the personnel files, and on the other hand, it is proved that the information given by Ford top officials to the military in order to carry out the kidnappings took the form of lists of people to be detained.

A strategic relationship between the military and the corporation

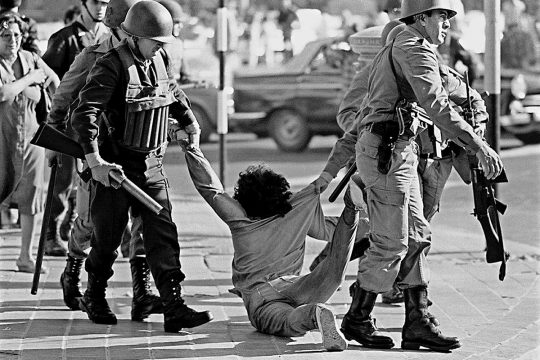

The judges also affirmed that it was proven with the same degree of certainty that there existed a logistical assistance, including through material resources (vehicles, food and gasoline), by Ford authorities and top officials to the Armed Forces who carried out the abductions. They also stated that the evidence showed that there was a contribution of the organizational structure and the territorial infrastructure on behalf of Ford authorities and top executives to the military in charge of the abductions. In particular, they underlined that after March 24, 1976, a sector of the recreational facilities “became a clandestine detention center with the particularity of being located within private property. Workers detained and kidnapped from their workplaces were brought to these facilities where they were kept in the condition of “disappeared.”

Third, with regards to the motives behind these criminal actions, the judges ruled that the elimination of the “comisiones internas” of the trade-union organizations within the factories, “which were symbols of the working class strength and resistance against the demands of higher efficiency, was a common goal between business leaders and the military who seized the goverment”. Furthermore, they considered that the workings of the labor market was yet another dimension of the project of social and economic transformation put into motion. This allows to understand the common denominator among the 24 victims, which was “their labor relation with Ford.” The judges added that there was “a strategic relationship between the military and a sector of the business leadership”, given that they had interests in common, namely to ensure what they considered a “normalization” of labor relations, and the profound transformation of the economic and social structure.

An effective contribution to the repression

Fourth, it is important to pay attention to the kind of evidence accepted by the court. Central importance was granted to the victims’ and their families´ testimonies, taking into account the characteristics of the crimes perpetrated in a clandestine manner that involved the systematic destruction of proof and documentation. A wide array of sources were also cited in the decision, including the oral presentations, written reports and conclusions provided by the expert or “context” witnesses, considering them “clarifying and conclusive.” In addition, the court particularly valued the book “Responsabilidad empresarial en delitos de lesa humanidad. Represión a trabajadores durante el terrorismo de estado” (Corporate responsibility in crimes against humanity. Repression of workers under state terrorism), which has been accepted as proof. But the court also used a variety of sources produced directly by the company, such as the minutes of the Board of Directors meetings, publications and public statements, interviews made with different business leaders, among many others.

As regard to the legal findings of the verdict, the court concluded that the two top business officials were “responsible of complicity by means of necessary participation”. This implies that while the authorship relied on public officials – in this case the military chief Santiago Omar Riveros – there was a functional co-authorship of Müller and Sibilla. Müller and Sibilla were not authors of the crime but they made effective contributions to the authors who had control over the criminal act. The crimes were the illegitimate captivity aggravated by violence and threats in 24 cases, and an extension of over a month in 15 cases. And they were the torments aggravated by political persecution in all cases. The court underlined that these crimes were possible thanks to the use of State resources in the hands of the military, but also thanks to the use of the resources and facilities of the factory, which was the everyday workplace of the victims who considered it a vital part of their development, their lives and those of their families. It was through the factory that business officials “contributed to the repressive apparatus of the State, providing information, means and facilities to the execution of crimes against humanity.”

The defense of labor rights

On March 24, 2019, during the mass demonstration in Buenos Aires, the main speech recalled the need to find ways to prosecute not only individuals but corporations themselves, demanding the immediate activation of the Congressional Commission to Investigate Economic and Financial Crimes during the dictatorship, which was approved by Congress in 2015 and never instrumented. Because of all this, the reasoning of the December 2018 decision does not only provide solid foundation to the Ford case, which concerns one of the most prominent multinational corporations in contemporary history. It is a reminder of the importance of trade-union organization and activity in the defense of labor rights and it paves the way for future trials and for other truth and justice initiatives addressing business involvement in violations of human rights.

VICTORIA BASUALDO

VICTORIA BASUALDO

Victoria Basualdo has a Ph.D in History from Columbia University, New York. She is a researcher at the National Council of Scientific and Technological Research (CONICET) and at FLACSO Argentina, where she coordinates the Program "Labor studies, trade-union movements and industrial organization". She was summoned as "context witness" at the Ford trial, called by the Secretary of Human Rights of the Province of Buenos Aires.