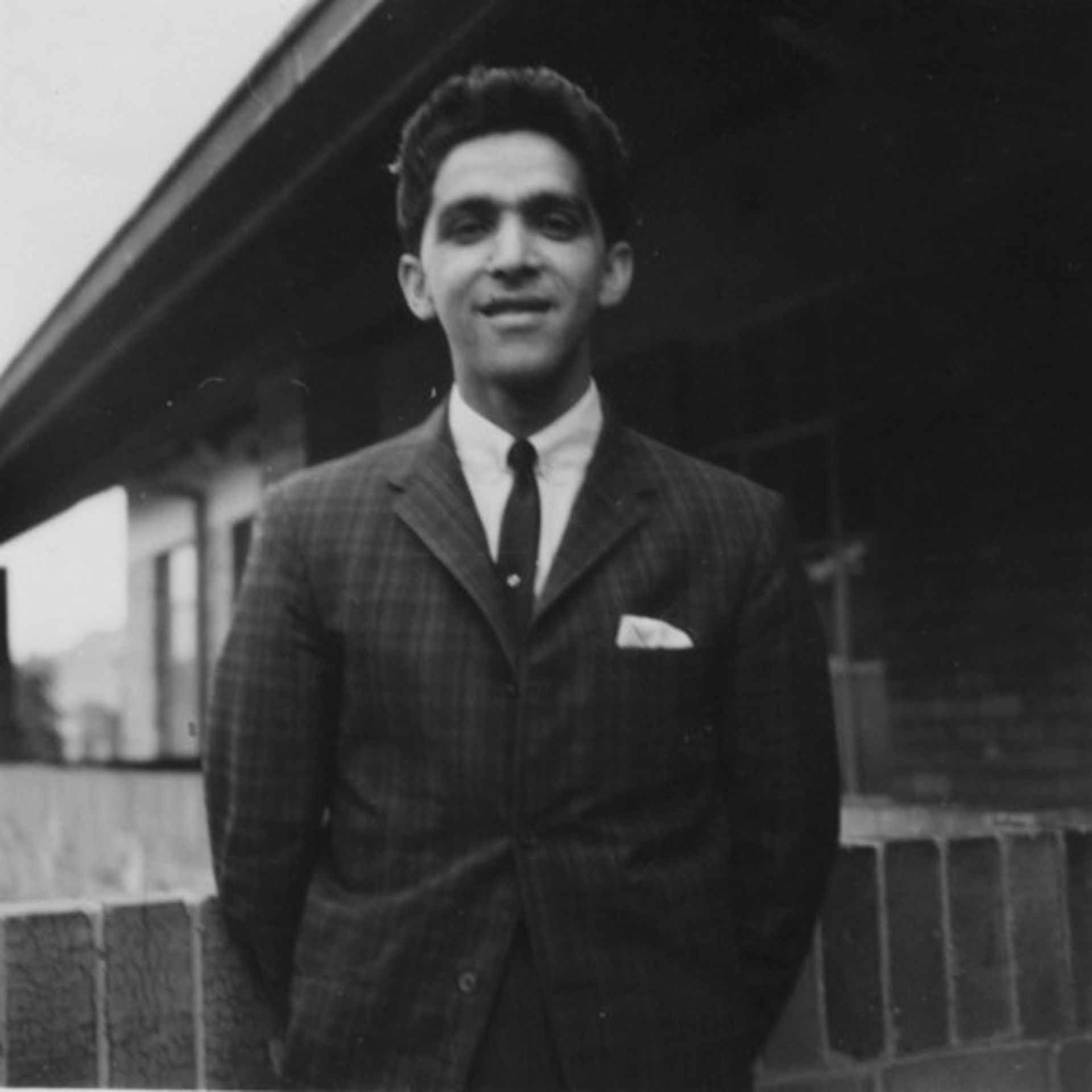

On 27 October 1971, the parents of South African anti-apartheid activist Ahmed Timol were informed that their son had committed suicide by throwing himself out of the window of room 1026 of John Vorster Square, the notorious police headquarters in central Johannesburg.

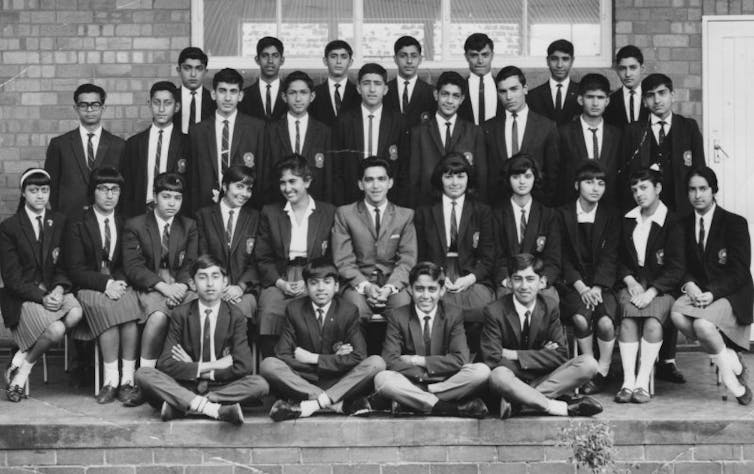

Timol was a member of the South African Communist Party. He was also a well-loved teacher. His family was convinced that he was murdered by the security police. This view was widely accepted by everyone who opposed the apartheid state at the time.

Writing under his pen-name “Frank Talk”, the black consciousness leader Steve Biko expressed his disdain for the patently fabricated claims:

The late Ahmed Timol was ‘prevented’ from dashing through the door but it was found impossible to stop him from ‘jumping’ through the 10th floor window of Vorster Square to his death.

Biko’s article appeared in the widely-circulated newsletter of the South African Students Organisation in early 1972. Not long after that the banned African National Congress (ANC) submitted a memorandum to the United Nations calling for South Africa’s expulsion from the world body and for the denunciation of apartheid as a crime against humanity.

The memorandum asserts what was common-knowledge at the time – Timol’s death was not the result of suicide but of murder. A short time later Magistrate JJL de Villiers ruled at an inquest that no one was responsible for Timol’s death.

It took 46 years for the truth about Timol’s murder to be recognised in a court of law. Although there have been significant cases that have provided evidence of the transformation of South Africa’s criminal justice system post-1994, this case is the first to enact what can be properly understood as restorative justice.

A judge has ordered that Joao “Jan” Rodrigues, a Security Branch clerk and ostensibly the last person to have seen Timol before his death, be charged with Timol’s murder and with defeating or obstructing the administration of justice. Rodrigues has sought a permanent stay of prosecution and the judgement in the matter has been reserved.

If the stay is granted it will apply not only to Rodrigues but to all former Security Branch and former state agents who would effectively be exempted from being held to account for their actions in the future. Rodrigues’s defence has argued that a trial against him would be unfair due to the time that has lapsed since Timol’s murder.

In another recent development South Africa’s Minister of Justice announced the re-opening of the inquest into the death of trade unionist Neil Aggett, who allegedly committed suicide after being detained and tortured by the Security Police in 1982.

In a similar way to those who committed crimes as part of the National Socialist regime in Germany during the Second World War, almost all of the apartheid-era perpetrators have been absorbed into civilian life and have not been punished.

The re-opening of these cases creates the possibility for the perpetrators to be tried for committing crimes against humanity. This has the potential to radically shift how people think about what apartheid was, how it continues to affect the present, and how people experience and understand impunity and injustice.

Victims of violence

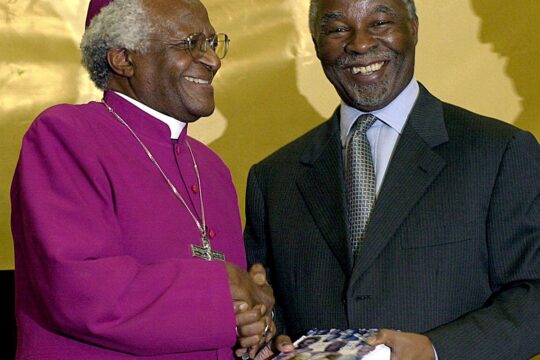

In 1995 a court-like body called the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was assembled in South Africa. Anybody who felt they had been a victim of violence during apartheid could come forward and be heard. Perpetrators of violence could also give testimony and request amnesty from prosecution. Hawa Timol testified about her son’s murder.

However, not one of the Security Police officers involved in Timol’s arrest and interrogation came forward. Nor did anyone ask for amnesty for their part in Timol’s murder. In 1971 he was the 22nd person to die in detention at the hands of the Security Police since the introduction of detention without trial. Timol was the seventh person to have allegedly committed suicide.

Following the TRC hearings, Imtiaz Cajee, Timol’s nephew, vowed to seek justice for his family. His extensively researched book, “Timol: Quest for Justice”, was published in 2005.

In 2017 the Timol inquest was finally re-opened. On 12 October Judge Billy Mothle delivered a landmark judgement and overturned the findings of the 1972 inquest. The judgement affirmed what the Timol family had maintained all along – Ahmed Timol did not commit suicide but was murdered by members of the Security Branch of the South African Police after being interrogated and tortured.

Justice delayed

In 2003 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s final report was released. Three hundred cases involving gross violations of human rights were handed over to the National Prosecuting Authority on the understanding that they would be investigated and that those responsible would be prosecuted.

In 2015, the state’s failure to pursue the TRC cases was exposed when Thembi Nkadimeng sought to compel the National Prosecution Authority to prosecute the Security Branch officers accused of torturing and murdering her sister, Nokuthula Simelane, an anti-apartheid activist who was abducted in 1983. It emerged that ‘political interference’ ensured that the matter was blocked.

On 5 February 2019 ten TRC commissioners wrote a letter to President Cyril Ramaphosa. They called for a commission of inquiry to investigate why the TRC cases have not been pursued. In their letter, the commissioners argue that:

The failure to investigate and prosecute those who were not amnestied represents a deep betrayal of all those who participated in good faith in the TRC process. It completely undermines the very basis of South Africa’s historic transition.

The re-opening of the Timol and Aggett cases deepens public knowledge and understanding of the many cases of people who were tortured and murdered under apartheid. It also serves as a reminder that those responsible for committing atrocities have almost without exception evaded responsibility and have never been held accountable for their deeds.

![]()

Kylie Thomas, Associate Researcher at the Institute for Reconciliation and Social Justice at the University of the Free State, University of the Free State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.