Nearly 11 years ago, on 14 August 2008, the Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) of the International Criminal Court (ICC) announced the preliminary examination of the situation in Georgia. The matter referred to the international armed conflict in Georgia’s breakaway region, South Ossetia, in what some commentators have named the first European war of the 21st century.

The region had been under the control of pro-Russian separatists since the early 1990s. Ongoing tensions and periodic armed clashes between the Georgian army and separatist forces escalated during July to early August 2008 with a series of explosions targeting, among others, both Georgian and separatist military and political leaders in South Ossetia. A fresh outbreak of hostilities between the Georgian forces and the separatists led to Russian military intervention on the side of the latter. After a week of fighting Georgian troops were forced to retreat as Russian Federation took control of localities in South Ossetia and extended control over a 20 km “buffer zone” established within parts of Georgian territory.

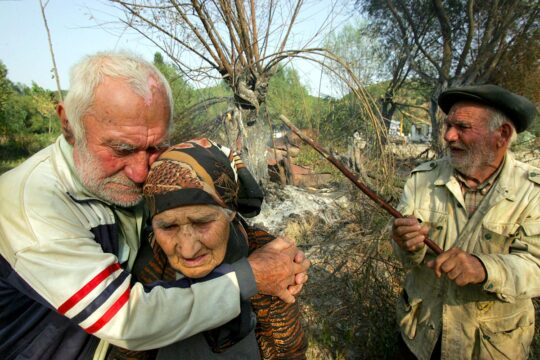

During the conflict, hundreds of people were killed, and the parties involved were accused of using disproportionate force that endangered civilians. Human rights groups reported that ethnic Georgians living in South Ossetia were deliberately pushed out of their homes by a campaign of terror that included scores of murders and around 27,000 have been unable to return since. Georgian forces were also accused of attacking Russian troops who had been deployed in the region as peacekeepers under an earlier peace agreement with the separatists.

An investigation opened in sensitive circumstances

After more than 7 years of preliminary examination, on 27 January 2016, a Pre-Trial Chamber of the ICC authorized Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda to open an investigation. According to the Chamber’s decision, investigation focuses on crimes against humanity of murder, forcible transfer of population, and persecution, and war crimes, including attacks against the civilian population, wilful killing, intentionally directing attacks against peacekeepers, destruction of property, and pillaging allegedly committed in the context of the conflict in Georgia between July 1 and October 10, 2008.

The investigation was opened during a particularly turbulent period for the ICC, when it was heavily criticized for being an inefficient, neo-colonial, Western institution targeting only African states. At the time, several states had been threatening to withdraw from the Court’s jurisdiction and were lobbying the African Union to adopt a strategy for collective withdrawal.

In these circumstances, opening an investigation outside Africa could enable the ICC to reinvigorate its original image of a court for all people, dedicated to end impunity worldwide. However, one thing that was evident for the observers from the beginning of the process was that the ICC was not ready for this investigation.

A court unprepared

In Georgia, the Court was stepping into the new region with a purpose to investigate crimes committed during an international armed conflict involving a permanent member of the UN Security Council. The ICC was unfamiliar to the Georgian and Russian contexts. Most of the Court officials involved with the situation did not know much about the local and regional history, culture and general state of affairs. Some of them considered French to be the official language of Georgia, as it was the case in half of the previous states they have been dealing with. More importantly, the Court came without a strategy and vision on how to handle the specific challenges of Georgia’s situation. Despite civil society warnings, the OTP’s cooperation advisers initially assumed that Russia would cooperate with the ICC. This assumption was disregarded only at the end of the first year of investigation when Russia withdrew its signature from the Rome Statute.

Throughout the first year there was very little activity from the OTP on the ground. In fact, Georgia seemed to be the last thing on the ICC’s mind. In February 2017 Prosecutor Bensouda stated that so far her Office had been dealing with “technical matters” and that more “specific steps” would follow soon.

To help the Court comprehend the local context and increase effectiveness of its activities, Georgia’s civil society recommended opening a field office in the country. This office was also anticipated to provide public information and conduct outreach activities amongst the affected communities and the general population to raise awareness about the ICC.

The poor start of the ICC field office

Since 2008, the conflict remains one of the most discussed issues in Georgia. This is the topic that drives internal politics of the country, as well as relationships with its neighbours and the outside world. Despite the importance of the issue, neither the victims’ communities nor the public had much information about the ICC and its proceedings. While proficient in the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights, local lawyers had no experience of dealing with the ICC. A proper understanding of the Court required vigorous public information and outreach activities.

After several months of active advocacy, in October 2017 the ICC’s Registrar visited Georgia and announced the opening of the field office. The Registrar stressed his readiness to “listen, learn and build cooperation” as the Court reported on its official twitter account. He highlighted that continued engagement with civil society was key to help raise awareness about the ICC in Georgia. He further reiterated that the opening of the field office would ensure better lines of communications between the Court and all relevant actors in Georgia.

This gave hope to many that after two years of delay the Court was getting on a right track. Soon after the Registrar’s visit, the head of the field office was appointed. The Court, however, sent a foreign diplomat to this position, who spoke neither Georgian nor Ossetian. The selected candidate turned out to have no knowledge of the ICC itself, so that additional time and resources were required to familiarize him with the Court.

For almost a year, the field office was vastly under-resourced, composed of only the head of the office and a temporary officer from headquarters. Despite the shortcomings, the office managed, through the help of the local civil society, to conduct several outreach meetings with small parts of the affected communities. However, communication with local media was limited to a bare minimum.

Political manipulation

Georgian political leaders took advantage of the lack of information from the ICC about the ongoing process and began to politicize the investigation. In the context of the last year’s highly contested presidential elections, they traded accusations about who was responsible for the 2008 conflict and about improperly influencing the ICC’s investigation. The accusations sparked intense public discussions about the ICC so that throughout last November the ICC investigation was the most popular topic on TV, radio, and social media in Georgia. Everyone in the country was talking about the ICC, including former and current government officials, opposition parties and, importantly, former and current army generals.

The debate revealed that the public does not know the details of the ICC process — not even basic facts, such as what is the scope of the investigation. People also mix up the ICC investigation with two separate proceedings, one initiated at the European Court of Human Rights and another at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) by Georgia against the Russian Federation in 2008. The ICJ was particularly confusing to the public as it is also located in The Hague, and no outreach has been conducted to explain the difference between the two courts. As a result, Georgians often think that there is an inter-state claim being discussed at the ICC.

Positive signals

There is a clear need for effective public information and outreach activities that can help to fill in the informational vacuum and minimize misinterpretations of the process. The Court cannot fulfil this task alone. It needs to continue listening, learning and strengthening its local partnerships to succeed.

Lately, there have been some positive developments in this regard. Early May, representatives of different organs and sections of the ICC, including the OTP, the Public Information and Outreach Section, the Victims Participation and Reparations Section, and the Trust Fund for Victims visited Georgia. They met the local civil society, arranged information sessions with the affected communities in various victims’ settlements, gave interviews to journalists, participated in TV programmes, conducted trainings for local lawyers on victims’ participation, and met with other relevant actors on the ground. These are positive signals.

The role of the Trust Fund

Throughout the last decade, many victims passed away. Thousands of displaced people are living in dire conditions, and civilians across the administrative border line are living in fear due to regular kidnappings and deterioration of the security situation.

In these circumstances, the Trust Fund’s early engagement is particularly important as most people do not anticipate the investigation to move to trial stage due to the non-cooperation of the Russian Federation. This feeling was amplified after the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber’s recent decision rejecting the OTP’s request to open an investigation into the situation in Afghanistan. In the eyes of sceptics, this decision has confirmed the suspicion that the Court will not be able to pursue perpetrators from powerful states.

The Trust Fund’s assistance mandate allows earlier engagement with victims even in the absence of a decision on guilt. Physical and psychological rehabilitation and material support, such as offering access to income generation and training opportunities, is what the victims need most. As such, the Trust Fund’s announcement in last September of initiating an assessment of the victims’ needs, to be followed by specific assistance projects, gave many victims a hope that the process could still be meaningful for them.

The period of 2019-2021 will be particularly interesting to evaluate the process. This is the fourth year of the investigation and not much is known about its whereabouts. It is important to see whether the OTP’s approach will be to bring cases against low-level suspects. This is the approach that the Prosecutor has suggested in her new strategic plan for 2019-2021. One should also keep in mind that due to Russia’s non-cooperation arrest warrants against any individual of South Ossetian and Russian ethnicity will most likely not be executed. A second factor to consider will be the scope of the cases and whether they fully represent the victimisation.

It is now time for the ICC to strengthen partnerships and have honest discussions and self-reflection about the lessons learned and to find joint solutions in the best interests of victims and justice.

NIKA JEIRANASHVILI

Nika Jeiranashvili is the Executive Director of Justice International, an NGO that supports International Criminal Court (ICC) investigations and civil society engagement in them. He was the Human Rights Program Manager and ICC Program Director at the Open Society Georgia Foundation.