JUSTICEINFO.NET IN-DEPTH INTERVIEWS

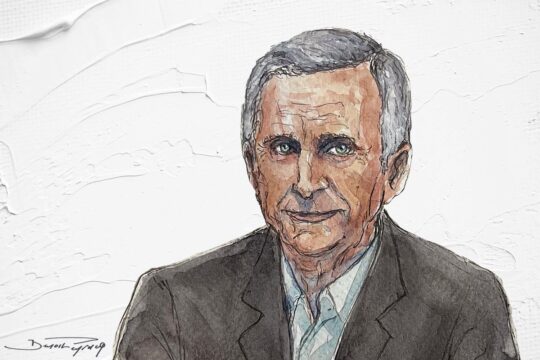

Françoise Mathe

Criminal lawyer at the Toulouse Bar and co-founder of Lawyers without Borders (ASF) France

This Thursday, November 7, a new universal jurisdiction trial opens in Brussels against a Rwandan accused of having participated in the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. In 2016, lawyer Françoise Mathe defended the mayor of a small town in eastern Rwanda, Octavien Ngenzi, in a universal jurisdiction trial held in France. She shares her thoughts on this "David and Goliath fight", as she has described the work of the defence in such trials.

JUSTICEINFO.NET: The Augusto Pinochet case in 1988 was a starting point in the history of universal jurisdiction. This trial never took place, but it raised high hopes for many human rights activists. Did this event also make you dream?

Françoise Mathe: I don't know about dreaming. But there were high hopes that for certain crimes, which are state crimes, there is no forgetting and above all there is no refuge. Those who committed these crimes will not find refuge, because to arrest and try them is not the exclusive jurisdiction of courts in the place their crimes were committed. That was the idea. For the international criminal justice of the Nuremberg Tribunal, the judge and place of trial were consequences of a war. In the Pinochet case it was peacetime, he was detained in London where he least expected it, years after the crimes for which he was responsible, by the judicial authorities of a country that did not have direct jurisdiction. When Pinochet was arrested, we were stunned. It was just so extraordinary. It was a revolution.

So it conveyed a message that the law was independent of politics?

I believe the fact that international criminal justice has a deterrent dimension is an illusion. But there was and still is the idea that those who are tempted to commit this type of crime must know that they will never find a safe and permanent refuge.

The process is reaching its limits because some people - including myself - have underestimated the political dimension.

Two decades after this surge of hope, can we say it has been fulfilled?

There are two ways of looking at it, whether it is international criminal justice or universal jurisdiction. The first is to say we are doing something, moving forward, it is a learning process, there are ups and downs, adjustments, improvements. We are in an imperfect process, but one that is destined to improve and has difficult beginnings for unavoidable reasons. The second is to say that the process is reaching its limits because some people - including myself - have underestimated the political dimension.

Let us talk about the International Criminal Court. Again, one way of looking at it would be to say that successive failures are the consequences, say, of people's imperfection. The other way of looking at it is to say no, the current failures are the result of a weakness inherent in the system, which means that the prosecution's choices necessarily obey political criteria. There is a kind of convergence between an institution which, like all institutions, wants to survive, function, improve, get its teeth into something, and States which feed it what suits them. This was overlooked by those who believed that it would represent magnificent and continuous progress.

Are things better before national courts, for example in Rwanda where you have worked on genocide cases?

Rwanda is a good laboratory because we have everything. We have transitional justice with the gacacas, national criminal justice, universal jurisdiction and international criminal justice with the Arusha court. I think that for Rwanda, international justice has not worked badly, with two or three reservations. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) was able to acquit, to adjust the sentences and the procedures were more or less balanced. The problem was at the prosecution level where one side was totally spared, a side which also committed crimes even if they were not as criminal as the other. This is a major political mistake, but in terms of how the trials were conducted, it seems very acceptable to me.

As for the criminal jurisdictions, if we overlook the fact that there too only one criminal party has been prosecuted, what I have observed is very paradoxical. First of all, there were a lot of acquittals: 25% acquittals is rare. There was also a range of sentences that shows the courts were able to individualize, and a procedural flexibility adapted to the local culture. At one point, I represented a womancalled Euphrasie Kamatamu. The magistrate of the specialized chamber, who was not a lawyer, looked around the room and asked: "Does anyone have any additional information to bring to this case?" People raised their hands. I said to the magistrate: "But you can't do that." He asked me why. But it was difficult to say why. And the only answer I found was to say that I had to be able to prepare my client for the hearing of witnesses, find contradictory witnesses, that I needed a delay. That's all. It wasn't that outrageous, actually. It did not go against international standards applicable in this country as elsewhere.

Isn't this the very expression of justice done under the eyes of the community?

Yes. And we must distinguish two things in the expression of that justice. The first is that it is not necessarily the expression of the truth, because society needs to rebuild itself and its unconscious objectives are to find the common version that will allow its members to continue living together. This also applies in ordinary cases. Then there is the common sentiment of revenge, of old resentments that pollute things. When it came to judging people of a high political level, it no longer worked either. But if we remove these two ends of the chain, we have justice that I have not found worse than that of the Paris Criminal Court in the Ngenzi case.

What was it that shocked you in that trial of Rwandans in Paris?

Everything. First of all, everything in the preparatory stage. When the trial arrived before the court, the investigation was already being built in a way that was unfair. This is French procedural culture, which allows cooperation between the bench and the prosecutor's office. Claude Choquet, who was at the time the coordinator of the investigating judges of the specialized judicial unit, said calmly during a symposium on the first genocide trial [the case of Pascal Simbikangwa] that the genocide unit was great because the judges and the prosecutor were in the same place and that they could thus develop common strategies. It's hard to believe we really heard that. And he seemed very happy about it. He explained that they had set up a common database in which all the files and all the legal, historical and geopolitical documentary research carried out by the judges' legal assistants and the public prosecutor's office were stored. It was a monumental database -- to which the defence had no access.

The judges and the prosecutor's office travelled together to Rwanda to conduct witness interviews, among other things. The lawyer was not summoned or informed.

And there are the famous on-site visits. The judges and the prosecutor's office travelled together to Rwanda to conduct witness interviews, among other things. They called it "on-site hearings" but it was not like what is usually called that. The lawyer was not summoned or informed. I have never had a case where the judge ordered an on-site proceeding and did not summon me. This is a violation of the rights of the defence, which seems to me to be quite massive.

Then came the trial...

First there is the preparatory phase. Each party gives his or her list of witnesses to the other party and has them called. The Code of Criminal Procedure provides that each party, civil party or accused, may request the public prosecutor to call up to five witnesses as his own, at the State's expense. This was ridiculous in this case, since the prosecutor's office cited 70 of them, more than a third of which came from Rwanda. I made a list of 25 witnesses, 20 of whom were in Rwanda. I was denied them. I couldn't bring witnesses from Rwanda at my own expense, I couldn't afford it. At that stage, there was still an imbalance between the parties.

The privilege of the defence to speak last becomes a terrible trap since you are faced with a witness who is exhausted.

And how did the civil parties weigh in the balance?

In France, the right to become a civil party, not only individually but also through associations, generates many civil parties, which in itself is legitimate, but their procedural rights are modelled on those of the prosecution and defence. Which leads to what you saw: you had 12 civil parties. I don't think the balance of the trial is a matter of numbers. On the other hand, given the rules of procedure, which consist in having all witnesses questioned first by the president, then by the assessors, then by the civil parties, then by the Attorney-General and finally by the defence, the privilege of the defence to speak last becomes a terrible trap since you are faced with a witness who is exhausted. And we are talking about a Rwandan peasant who is not prepared to stand up and answer questions for hours.

But all this is a reflection of the defects in our criminal procedure, it is not the fault of universal jurisdiction.

Whatever the quality of the participants, we are talking about facts that took place more than 20 years ago, at a significant geographical and an even greater historical and cultural distance. The scope for misunderstanding is huge.

The most characteristic feature of universal jurisdiction is trials at a distance. What was your experience of that?

Whatever the quality of the participants, we are talking about facts that took place more than 20 years ago, at a significant geographical and an even greater historical and cultural distance. The scope for misunderstanding is huge. The evidence has deteriorated over time. People are rebuilding their memories. I'm not saying they're lying, but there are also some who are lying. When you retell a fact, it is through what is important to you in your conscious or unconscious. However, what is important for the judge of the Paris Assize Court, for the Attorney General, for the lawyers of the civil parties or the defence - I am talking about the details, the colour, the smell, the distances - is not seen from the same angle by a Rwandan peasant, illiterate or not. And so there is a very high risk of misinterpretation, to use a neutral term. This risk exists regardless of the quality of the stakeholders. And if, on top of that, the participants do not make an effort, it is a disaster.

Do you have examples from this trial in France?

When, after two weeks, almost everyone systematically continues to deform place names repeated a thousand times in the trial in such a way that the witness doesn't understand them, that the essential elements of these people's daily lives are totally unknown, this makes the trial a dialogue of the deaf. I remember a witness I heard on video conference. He is an old man, who is probably an authority, a tall, handsome, dignified, very serious old man, with a traditional stick. He is asked questions that he understands as well as he can and to which he answers as well as he can. And, at one point, he said, "Anyway, I already told all this to the gendarmes who questioned me and it all went on television." There is a stunned silence, until someone realizes that the gendarmes typed the interview and scrolled it on a computer screen, which for him is a television, because that's the only technology he knows. And it ends - in the face of this man who sees and hears us - with a gigantic burst of laughter. It is a public humiliation. This testimony, on which one of my accused [Ngenzi, who was tried alongside another Rwandan mayor, Tito Barahira] counted a lot, ended in this kind of farce.

The role of a lawyer in a case like this is to try to pass on what has been understood over time, to avoid misunderstandings.

So what is the role of defence counsel in this context?

The role of a lawyer in a case like this is to try to pass on what has been understood over time, to avoid misunderstandings, with varying degrees of success. And to try to make the accused understand how the mechanism he faces works.

What do you think you failed to transmit?

To whom? That's the question. I think that some jurors had understood the relativity of the roles within the municipality of Kabarondo. For those who wanted to listen, it was possible. The central issue in the Ngenzi case is the respective roles of civilians and the army. This is the grey area.

There were several phases in this case. There’s the time from the day after the 6 April 1994 attack [on President Habyarimana's plane, an act considered to have triggered the genocide] to the morning of 13 April, the day of the attack on the Kabarondo church. There is the period before the attack on the church, the attack, and after the attack. What Ngenzi said, which seems reasonable to me, is that until the 13th, there were limited massacres in the communes and that he went to the villages, calmed people down, brought the wounded to the hospital and health centre, and those who wished took refuge in the church, where they thought they were safe, because they always had been. In this phase, he is not even in a grey zone, he does what he can with ridiculously little means.

Then there was the attack on the church. The prosecution's theory was that he went to get the army. It doesn't hold for a second. The question of whether he was present and accepted, present and happy, present and terrorized, that is the real question. This is what I call the grey area.

Then there is the third phase, after the massacre at the church, where there are more systematic massacres, Interahamwe [Hutu militiamen] from Kibungo arrive and he is accused of having been present. Here again, the question arises: present and accepting, present and participating, present and trying to calm things down? These subtleties, without violating professional secrecy, had obviously been well understood by some jurors. You couldn't say that there was one wicked person who came along and organized everything, it wasn't sustainable.

They didn't want to enter another world. They wanted to be in a world of cause and effect, relationships and responsibilities as simple as a robbery at the French savings bank.

Did you observe any major moments of cultural misunderstanding?

There's the story of the cows belonging to Titiri [a Tutsi cattle raiser killed during the genocide]. Through the testimonies, we witnessed the birth of a rural myth. Ngenzi was said to have accused the villagers of eating Titiri's cows, or his goats according to some, while he was still alive [suggesting that Ngenzi wanted Titiri dead]. We see the myth being built. And I had the impression that the judges didn't want that at all. They didn't want to enter another world. They wanted to be in a world of cause and effect, relationships and responsibilities as simple as a robbery at the French savings bank.

How were the witnesses treated?

There were two kinds of witnesses. There were survivors. Most of them looked good physically, except for one or two widowed women who were obviously forgotten or abandoned. These women were very distressing. Then there were the former convicts of the gacaca or the ordinary courts. Some appeared by videoconference, some in person. They were coming from their village. All of a sudden, they crossed not only miles, but centuries. They were flying for the first time in their lives. They landed at 6:00 in the morning. An association would put them in a hotel and give them a bad suit to appear at the hearing. There were two or three suits that were passed around and adjusted with pins. We could see the pins on the pants of those who were less tall than the others. They arrived at the hearing at 2:00 p. m., and left in the evening. I find this extraordinarily brutal.

I don't think there's any communication possible. The testimonies collected in these conditions are meaningless, whether they condemn or exonerate.

What impact did this have on the trial, in your opinion?

I don't think there's any communication possible. The testimonies collected in these conditions are meaningless, whether they condemn or exonerate. Often, in a trial procedure, there is a moment of communication between witnesses, magistrates, lawyers, the Attorney General, and something happens. But there was such a barrier there...

The judges could not grasp the humanity of it. None of us is certain what they would do in the middle of this chaos, this tragedy. I remember a damning testimony for Ngenzi, that of Hosea Karakezi, who had been his spiritual father, a teacher who had helped him to become what he was. Karakezi was imprisoned after the genocide. I think he was only released because of the influence of his wife, who is from an important old Tutsi family. And Ngenzi loved this woman, Jacqueline. She too came to testify and was overwhelmed with tenderness for him. But this remains invisible. This was a key moment when the court really didn't want to understand.

There was another time when a lovely couple appeared who were the mayor's former assistant and his wife. It was a moment of relief because a moment of humanity. She's wonderful, his wife. She's dressed in yellow. She is Ugandan. She's a ray of sunshine. Then David, the former assistant, testifies. He makes a statement that is not so damaging, that is interesting, and Ngenzi smiles. He's happy to see them. And he says to me "he's a good boy", because what this boy, who is a policeman today, is saying represents the line between what can be said so as not to hurt Ngenzi too much and not to be bothered too much on the way back. Ngenzi smiled and the president of the chamber chastised him. "What are you laughing at?" he asked. It's not a personal criticism... but it's a lack of cultural understanding.

There was at all times during the trial, among the magistrates and the lawyers of the civil parties, the desire to match the account of this trial with their representation of genocide as represented by the West at Auschwitz. As if the Western experience was prevalent in the preparation and execution of genocide in Rwanda.

That is an anecdote. On the other hand, the structural aspect is that there was at all times during the trial, among the magistrates and the lawyers of the civil parties, the desire to match the account of this trial with their representation of genocide as represented by the West at Auschwitz. As if the Western experience was prevalent in the preparation and execution of genocide in Rwanda. They were looking for every detail to validate the idea that it was the second Shoa. This leads to misjudgement and understanding nothing. That does not mean that it is not genocide. I mean, there is no universal mechanism that would necessarily lead to genocide. It was absolutely terrible, this willingness to apply a given idea.

My view is that there was no planned genocide in Rwanda. There were local genocidal mechanisms, which were not the same. If you take a macro view, you get the impression that it was the same everywhere. But when you look at it region by region, you see that the agenda was not the same. It all depended on the geographical and military situation in each place in this very small country, and at what point in the conflict. For me, the genocide was a stage of the war. That does not change its nature, it does not justify it, but it allows a better understanding of what happened.

And you couldn't convey that either?

You can't do that alone. We needed the experts. André Guichaoua refused to come. He was the one who could have done it, because he has knowledge through the archives of the Arusha court and through his long work in Rwanda. He was, in my opinion, the only one who could have brought a more nuanced interpretation.

I think that international justice is better suited to judge in a balanced way. First of all, because it creates its own criteria, its own scale of punishment. To judge is to weigh up.

Do you think that such trials should not be held, but you don’t dare to say it?

Oh no, I still believe in it. Total universal jurisdiction would be a kind of grand contest of political correctness and judicial imperialism – that’s madness. But it is clear that, when persons suspected of serious and imprescriptible crimes are in a territory and the State on whose territory they find themselves considers that they should not be extradited, that State must try them. I have no doubt about that. But I think that international justice is more capable of judging them than national courts are. I think Ngenzi and Barahira would have been much better judged in Arusha. I think that international justice is better suited to judge in a balanced way. First of all, because it creates its own criteria, its own scale of punishment. To judge is to weigh up. This is the whole problem of adapting the scale of sentences to exceptional circumstances. There are days when I think that French judges just after the Liberation might have been better able to judge these cases.

What did they have that today’s judges don’t?

They had experienced war. They knew horrible relatives who resisted and nice neighbours who collaborated, as well as poor guys who didn’t know how to make a choice and people who made unexpected choices. I think they had an awareness of the complexity and a certain humility which is harder to find today.

The educational and restorative value, the litany that unfortunate people repeat when they say "I need the trial to rebuild myself", I don't think that's true.

So finally, what is the purpose of these trials?

The purpose of a criminal trial is to punish a crime. We should not seek any further. For me, that's all it is. I don't believe in anything else. The educational and restorative value, the litany that unfortunate people repeat when they say "I need the trial to rebuild myself", I don't think that's true. I even think that it is dangerous to make victims believe that they need a trial to "rebuild" themselves. In that trial, most of the people I saw - with the exception of the two widows, who were forgotten by all, despite their suffering - were successful people who had rebuilt a social status and who absolutely did not need the Ngenzi trial in France to rebuild themselves.

On the other hand, I am certain that criminals must be tried. Criminals must be judged because, in a national and international society with a backbone, crime cannot go unpunished. But they must be judged fairly, with mechanisms that avoid error, and they must be judged in a measured way, that is, with the right tools for delivering fair sentences.

Interviewed by Franck Petit, JusticeInfo.net.

FRANÇOISE MATHE

Françoise Mathe is a criminal lawyer at the Toulouse Bar and co-founder of Lawyers without Borders (ASF) France, of which she was vice-president. She has carried out numerous missions as an observer for the International Federation for Human Rights and as an expert for the European Union in the field of transitional justice in Latin America, particularly in Peru and Colombia. She has represented and defended clients before the Rwandan courts in genocide cases (1998) and before the French courts under universal jurisdiction in matters of torture, genocide and crimes against humanity (2010-2016).