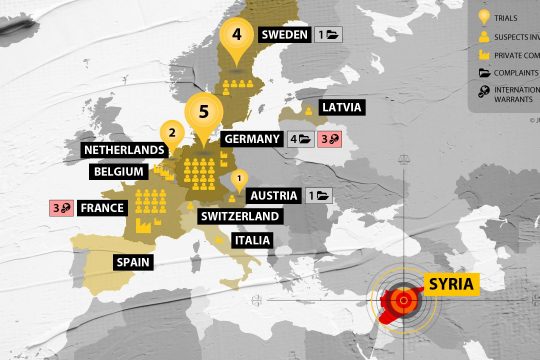

There is “renewed interest in prosecuting companies and businessmen” says international criminal law expert Guénaël Mettraux, although prosecuting corporate actors for war crimes is not new, since there were several precedents after the Second World War. He thinks this is at least partly “because of difficulties associated with the investigation and prosecution of actual perpetrators and the relative ineffectiveness of efforts towards that goal over the last few years”.

“There are a lot of NGOs who have looked at what has happened over the last few years and realized that the prosecution of perpetrators was extremely difficult, extremely challenging at every level, and some of them have turned their attention to companies,” says Mettraux, who is also a consultant for Lundin Petroleum, a Swedish company whose top executives are facing prosecution in Sweden for allegedly aiding and abetting war crimes in Sudan.

NGOs and national prosecutors may have scored an early victory with the Lafarge case in France and the Lundin case in Sweden, but it is not sure they will ultimately succeed, adds Mettraux. “The threshold that some would like to place on businesses and business actors is extremely low, and that's not the standard that was set, for example, after the Second World War, or the one now applicable as a matter of international law,” he told JusticeInfo. In all the Second World War cases, he says, “those who were convicted were people who were immediately and directly involved in the commission of the crimes or their furtherance, not some legal constructions resulting in theoretical attribution of liability”.

Syria: Lafarge financing jihad?

French cement giant Lafarge, now part of the Franco-Swiss Lafarge-Holcim group, was cleared by a French court on November 7 of complicity in crimes against humanity over its operations in Syria. “The investigating chamber came to the same conclusion as us, that there are no elements to justify prosecuting Lafarge SA for this crime,” said the company’s lawyers Christophe Ingrain and Rémi Lorrain. “The court recognizes that Lafarge has never participated closely nor from afar in a crime against humanity”. The court nevertheless upheld charges of “financing terrorism”, “violation of an embargo” and “endangering the lives” of former employees of Lafarge’s Jalabiya plant in Syria.

Eight senior officials of the company, including two former chief executive officers, were indicted in France in June 2018 under criminal law, while the company itself is also charged. It is accused of having financed jihadists in Syria, including the Islamic State group. Lafarge is suspected of having paid nearly €13 million via a subsidiary to intermediaries and armed groups. The payments were reportedly made in 2013 and 2014 to maintain production in its Jalabiya plant, as the country’s civil war escalated.

The French court also refused to recognize NGOs as civil parties in the case. They have announced their intention to appeal.

South Sudan: Lundin Petroleum fueling oil wars?

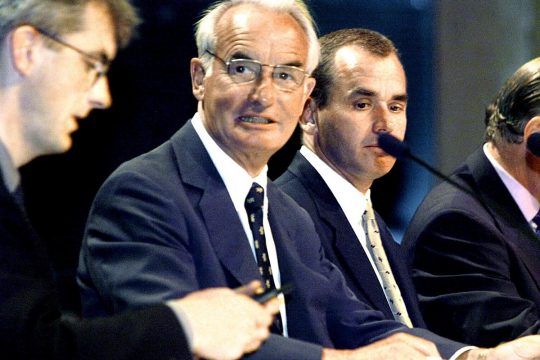

The Lundin case in Sweden is also potentially precedent-setting. The Swedish government gave a green light in October 2018 for the prosecutor to charge two top executives of the Stockholm-based Lundin Petroleum company for allegedly aiding and abetting war crimes in Sudan between 1997 and 2003 by fueling the country’s oil wars in the south. The company’s Swiss CEO Alex Schneiter, who was head of exploration at the time, and Swedish chairman Ian Lundin could face prison for life.

The case was opened in 2010 after a report published by the European Coalition on Oil in Sudan (ECOS) was sent to Sweden’s public prosecutor. According to aid and human rights groups, up to 12,000 Sudanese died of starvation and 160,000 people were displaced in areas were Lundin was active between 1997 and 2003. The ECOS report says that “the actual perpetrators of the reported crimes were the armed forces of the Government of Sudan and a variety of local armed groups that were either allied to the Government or its main opponent, the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A)” but that an oil consortium led by Lundin “may have been complicit in the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity”.

Investigations by both defence and prosecution are still ongoing, and no indictment has yet been made public. But Egbert Wesselink, a Netherlands-based researcher and activist who helped bring the case, says there is a “very strong expectation” that it will go to trial, possibly starting in late 2020. “The Federal Prosecutor has been working on this for almost 10 years, he has not ever given the slightest suggestion that he’s struggling with it, quite on the contrary, and the fact that he’s doing additional investigation after studying additional evidence is usually an indication that he has found supporting evidence for his indictment,” he told JusticeInfo. Wesselink recognizes, nevertheless, that “you never know, it is uncharted territory” and that “the defence lawyers are extremely aggressive”.

Darfur: BNP bankrolling genocide?

Other companies are also targeted by NGOs for alleged complicity in international crimes in conflict zones. Nine Sudanese victims, supported by the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH) and Project Expedite Justice, recently filed a criminal complaint asking French judges to investigate BNP Paribas for alleged complicity in crimes against humanity, torture, and genocide in Darfur, as well as financial offences. “This complaint marks the first attempt to hold the French bank criminally responsible for alleged complicity in international crimes committed in Sudan, and Darfur in particular,” says FIDH. “Between at least 2002 and 2008, BNP was considered to be Sudan’s ‘de facto central bank’.”

Former Sudanese president Omar Al Bashir, in power at the time, remains under two International Criminal Court arrest warrants for genocide and crimes against humanity in Darfur.

“Behind the gravest crimes and human rights violations there is always money,” says lawyer and FIDH honorary president Patrick Baudouin. “By granting the Sudanese regime access to international money markets, BNP allowed the government to function, to pay its staff, military and security forces, make purchases abroad, all while Sudan was a pariah on the international scene for planning and committing crimes in Darfur.”

Prosecuted in the United States for dealing with Sudan, Iran and Cuba in violation of US sanctions, BNP has admitted to acting as Sudan’s foreign bank between 2002 and 2008. It entered into a plea agreement and the case led to a record $8.9 billion fine in July 2014. But Sudanese victims did not receive any compensation, as the US Congress diverted the funds to victims of domestic terrorist attacks.

South Sudan: Asian companies fueling atrocities?

US-based NGO The Sentry also recently pointed the finger at Chinese-Malaysian oil conglomerate Dar Petroleum in South Sudan for involvement in atrocities there. In a recent report it says South Sudan’s war has been fueled by a multitude of international interests.

The Sentry says it has E-mail evidence that Dar Petroleum provided diesel fuel over a prolonged period (at least from September 2014 to mid-2015) to a government-aligned militia in South Sudan’s Upper Nile state which went on to commit well-documented abuses against civilians, including random killing, rape, abduction, looting and arson. From that evidence, it has been able to plot shipments “in support of active conflict patterns”, according to The Sentry’s Investigations Director J.R. Mailey. “They were definitely aiding and abetting those who went on to commit crimes against humanity, and the support for a non-state armed group is pretty problematic in itself,” he told JusticeInfo, “so I would say there was a level of complicity of these international actors in the extension of the conflict.”

No international convention

It seems unlikely, however, that there will be any legal action for international crimes against the Chinese and Malaysian state oil companies. As for BNP, it remains to be seen what the French judges decide.

"I see of course some merit in making business actors liable if and when they are involved in the commission of international crimes, but really the question now is where is the threshold that you should be aiming for," says Mettraux. What he would like to see is "greater clarity on what the expectations are about businesses and business people, so that the right cases can be gone after and there is greater coherence in the application of international law". "I mean if every state would agree in an international convention, or otherwise set particular standards for their companies, that would be something I'd welcome."