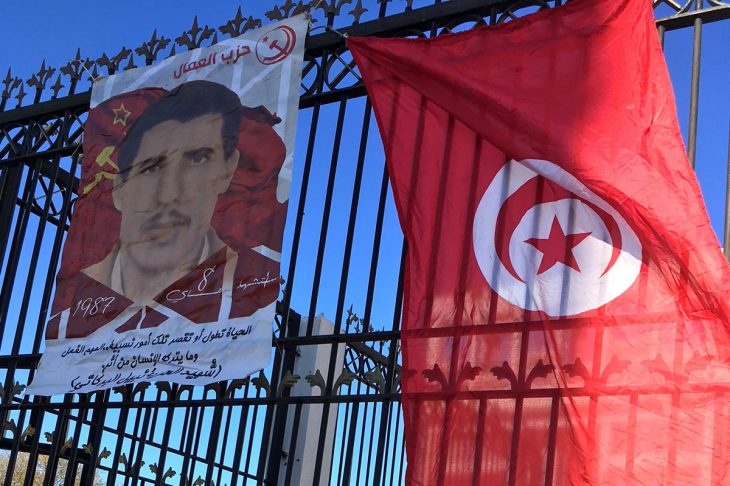

In a room packed to overflowing with activists from the Workers' Party -- formerly known as the Tunisian Communist Workers' Party (Poct) --, dozens of human rights activists and members of several political families, the eighth hearing in the Nabil Barkati case was held on 3 January before the specialized chamber in Kef (175 km north-west of Tunis). Barkati, a Poct activist, died aged 26 in his hometown of Gaâfour on the night of 7-8 May 1987, following his arrest by police and repeated torture.

Despite the absence of the accused and their lawyers, the Barkati case, which opened on 4 July 2018, is probably the most advanced of all the trials currently taking place before the thirteen specialized chambers set up in May 2018. Ridha Barkati, brother of the victim and chair of the “Mémoire et Fidélité” association created in Nabil’s honour, sees this as a hopeful sign. In 2016, Ridha Barkati managed to get May 8 designated as National Day Against Torture. He is now convinced that the whole truth will come out about the death of his brother, who over the years has become a symbol, a myth and a martyr of the Workers' Party. "Most of the defendants and witnesses have now appeared in court. I think the next session will be dedicated to the lawyers' arguments," he says, smiling confidently.

Nabil Barkati’s torture and the Gaâfour revolt

The date of that last hearing was symbolically charged. The Bread Riot took place on January 3, 1984, and it was on January 3, 1986 that the Poct was secretly born. As a teacher, trade unionist and Poct activist, Nabil Barkati adhered early on to a tradition of solidarity with the underdogs and forgotten people of his country. On April 28, 1987, he was arrested after distribution of a leaflet denouncing the confrontation between President Bourguiba's government and the Islamists. The leaflet also called on the Tunisian people to fight for "bread and freedom". Officers at the Gaâfour police station subjected him to the worst forms of torture, including being put in the “roast chicken” stress position, having his nails and teeth pulled out, being whipped and beaten until his leg was smashed. But he refused to say a word against his comrades and his party.

At a public hearing of the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD) on 18 November 2016, Ridha Barkati testified to what he said security authorities told him at the time: "Unfortunately your brother did not get a professional torturer!”

Nabil Barkati was found dead, half-naked, on 8 May 1987, near a railway track a few metres from the police station. He was shot in the head, with a gun placed behind his leg to substantiate the theory of suicide. The family was alerted and Ridha was one of the first to identify his brother's body, "despite the bruises everywhere and the death mask of his face frozen in an expression of terror," he recalls.

Then Gaâfour rose up. The wave of protests led by the victim's neighbours, comrades and relatives led the authorities to establish a two-week curfew in the region. On the 16th day, in order to calm popular anger, Minister of the Interior Ben Ali (the future President, who took power on 7 November 1987) ordered the arrest of the Gaâfour police superintendent. The latter was sentenced in December 1991 to five years in jail for ill-treatment, after a trial that his lawyer Habib Ziadi denounced as botched and unfair. Two of the commissioner's colleagues were sentenced to three years in prison for complicity. The magistrates at the time refused to abandon the thesis that the victim had committed suicide.

Precious witnesses

The charges are no longer the same as they were thirty years ago, as a result of the investigation conducted by the IVD before the file was transferred to the Kef specialized chamber. Now the charges are intentional homicide, torture, arrest and detention without any legal order, and concealment of evidence. Since the events, the head of the police post has died, but his subordinates and alleged direct torturers of Barkati - the two officers imprisoned in 1991, who are among seven people accused of causing his death - have been questioned by the president of the court. They admitted to torturing him but denied having participated in his murder.

"They continue to claim that Nabil escaped from the police station by stealing a gun, then climbed a fence despite his broken leg, and then committed suicide some 300 metres from his place of detention,” says Ridha Barkati. “Last time, the president of the chamber asked one of the defendants: 'And he hid the gun behind his leg? Is that possible?''

During the seven previous hearings, several valuable witnesses came forward: the public prosecutor who had led the investigation from 9 May 1987; forensic doctor Moncef Hamdoun, who first denied the hypothesis of assassination but then more or less confirmed it, saying the circumference of the hole in Nabil's head seemed too small for a point-blank shot, thus demolishing the theory of suicide. The former president of the Gaâfour football team also came to testify that members of the security corps would come to a bar he owned at the time and, after a few glasses of wine, speak openly about that night of crime and its perpetrators.

"May no Tunisian mother endure my ordeal!”

Civil parties’ lawyer Mokhtar Trifi, representative of the World Organisation Against Torture (OMCT) in this case and former president of the Tunisian League for Human Rights (LTDH), is less optimistic than Ridha Barkati about a speedy outcome for the trial. "Five other defendants, who may hold some of the truth, have not responded to the court's summons," he says. "We have asked the president of the chamber to issue warrants for the remaining defendants. But two problems remain. Thirty years after the events, some of the defendants have died or changed address. And there is a lack of cooperation by the judicial police whenever there’s a question of forcibly bringing some of their colleagues." As the lawyer goes to the car that will take him back to Tunis, he concludes with a note of bitterness: "The doubt that hangs over the case always benefits the accused, as they say.”

Ridha Barkati is now 65 years old. His wish to transform the Gaâfour police station (one wing of which was burned down during the Revolution nine years ago) into a museum against torture was recorded in the final report of the truth commission. This film-lover, a man of culture, human rights defender and fervent campaigner against torture and the death penalty, keeps repeating: "We are not asking for financial compensation. All we want is for the truth to finally come out and for an apology to be made to my brother's family and friends. We are capable of forgiveness. My mother left a vow as a legacy 'that no Tunisian mother should ever again endure my ordeal’.”