The work of the Truth and Dignity Commission (IVD) officially ended in December 2018, but the Commission has not completely closed its doors. If you move up from the lower part of the building, you discover that on the third floor people are working with great energy from early in the morning. The other four floors formerly occupied by the IVD in the Montplaisir district of Tunis were emptied and deserted several months ago, leaving only silence. But on the third floor, dozens of workers are stirring like a buzzing hive. For several days now, they have been putting the finishing touches to the transfer of the Commission’s archives to the headquarters of the National Archives. This is the last mission of the IVD, which lived in this building for just over five years, the time it took to compile the victims' files, listen to them, investigate cases of serious human rights violations and draft its final report.

Nearly 10,000 boxes

The law of 2013 governing and organizing transitional justice in Tunisia stipulates that "the Commission entrusts all its documents and files to the National Archives or to an institution created for the purpose of preserving the national memory". The IVD has long hoped for the second alternative, an institution similar to the Institute of National Memory in Poland and Slovakia, or the Research Institute on Totalitarian Regimes in the Czech Republic. However, since the authorities had not set up a special structure for the dictatorship's archives, the IVD was obliged, almost reluctantly, to hand over all its documents to the National Archives and its audiovisual recordings, containing the closed door testimonies of the victims, to the Office of the Prime Minister.

These key documents contain part of the truth about a dark history of human rights violations. They are also a likely target for hacking or leaking. And they are a major issue for many stakeholders such as researchers, historians, journalists, judges, victims and politicians.

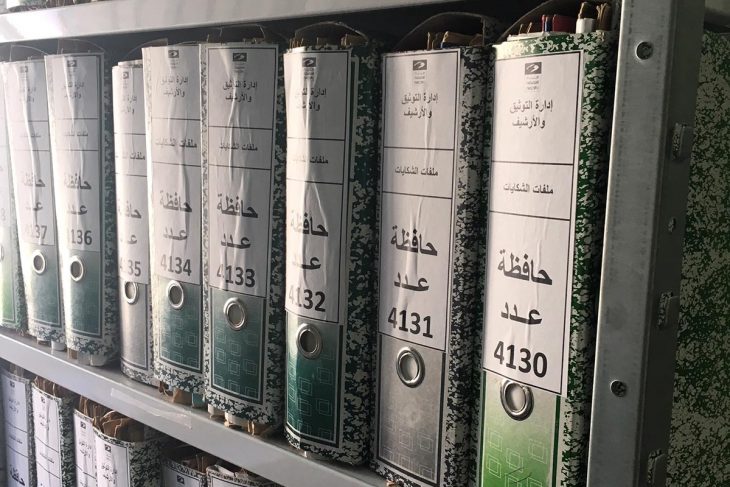

Nearly 10,000 boxes of archives are being transferred.

Precious documents and victim protection

The head of the archives department at the IVD, Belgacem Faleh, details the contents of these boxes, which are divided into three main categories. "First there are the files of victims' complaints, which are contained in 6,851 archive boxes. Then there are the archives collected during the Commission's investigations, covering the entire period of its mandate, from 1955 to 2013. These documents are contained in 182 archive boxes. Finally, there are the archives produced by the IVD, namely the minutes of the meetings, decisions of the Council and the documents of the various commissions. They fill more than 750 boxes.”

Faleh says that some of the most important files are those found in the presidential palace in Carthage, signed by former President Ben Ali himself, the files of Ben Ali’s ruling party (the Constitutional Democratic Rally, RCD) and diplomatic archives. This "treasure" also includes the files of the Ministry of Justice and the archives of the special courts at the time of Bourguiba, created in particular against the "Youssefists" (first opponents of Bourguiba in the 1950s) and the "Perspectivists" (Marxist students of the 1960s and 1970s).

Belgacem Faleh stresses the protection of victim identities. The boxes containing their personal data do not carry anything to identify them. As each victim has a number, you have to refer to a CD (which has also been handed over to the National Archives) to find the identity of these victims of serious human rights violations.

80,000 gigabytes of audiovisual testimonies

Audiovisual archives are a particular area of conflict between the IVD and the National Archives. Taking up 80,000 gigabytes, they contain thousands of hours of recordings of victims’ stories of rape, torture, police violence, harassment, humiliation, blackmail, deprivation of basic rights, unfair trials, inhuman prison conditions, etc. They include secrets, stories and accounts sometimes entrusted for the first time to a listener during closed-door hearings in the various offices of the truth commission. These valuable testimonies were used by the IVD commissioners as essential material for the drafting of their final report and by its investigators in cases subsequently transmitted to the specialized chambers. For historians, they constitute a mine of information.

But the IVD has delivered these "archives of the soul", as the historian and documentalist Abdeljelil Temimi calls them, to the Office of the Prime Minister and not to the National Archives. The IVD explains this decision by the absence of a specific law on access to these human rights archives. In its report, it recommends the creation of such a legal framework. It also expresses the need to "protect witnesses, victims, experts and all those it heard, whatever their status, from violations (...) by ensuring security meaures, protection against attacks and the preservation of confidentiality". But this transfer to a different place is also a symbol of the open war between the former president of the IVD and the director of the National Archives.

“Reconciliation" through archives

Hedi Jallab, director of the National Archives, thinks that current legislation is enough, and that it guarantees the security of these audiovisual documents through the archives law of 2 August 1988 - "one of the best laws in the world in this sphere" - and new legislation on access to information and protection of personal data.

The National Archives is financially autonomous but operates under the supervision of the Prime Minister’s Office. This attachment to the executive leaves some NGOs active transitional justice like Avocats Sans Frontières (ASF) and Bawssala (Compass) with reservations about the independence of the National Archives.

ASF says legislative reform is necessary “to limit the control exercised over the National Archives by the Executive with regard to the archives of the IVD and to define the obligations of the National Archives with regard to the preservation of the national memory". ASF and Bawsala also say the National Archives must have resources specifically dedicated to memory preservation activities and that the capacity of its staff should be boosted to specialize in the development of this precious collection.

Hedi Jallab intends to work first with his teams on describing and indexing these documents to put them on a database accessible to researchers. But he does not seem to have a clear strategy for showcasing the truth commission’s legacy and bringing it to life. Instead, he is relying on consultations that have already begun, "in serenity and calm," he says, with the victims and their associations to establish a programme for exploiting these archives. "If the transitional justice process, which I think has been badly steered, has not achieved the required consensus," he says with a barb for the former president of the IVD, "we do not want to miss the boat with the archives again. The ideal would be for these documents to make the objective of national reconciliation real".

Given all the desires and apprehensions, it seems the battle over these archives of living memory has only just begun.