For decades the Central African Republic (CAR) has struggled under the weight of the spectacular and everyday violence imparted by political elites. CAR’s most recent conflict – a six-year civil war between Séléka militants and anti-Balaka “self-defense” militias – has amplified CAR’s historical pattern of political hopefuls seizing power whilst shirking responsibility for violence. Such an arrangement results in what the International Crisis Group called a “phantom state” in 2007: the state is as damaging in the ways it is present in the lives of Central Africans as in the ways it is absent.

Without a functioning state, armed groups, CAR’s armed forces and international peacekeepers consistently use sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) as a tool of war with impunity. This article makes the case that the International Criminal Court’s (ICC) own practice of selecting only certain commanders as those “most responsible” for the “most serious” violence may very well be the cause of its consistent failure to meaningfully and adequately realize accountability for crimes of SGBV. It suggests that for CAR, the ICC actualizes a phantom justice, one that is as damaging in the ways it determines criminal culpability for SGBV as the ways in which it fails to actualize justice for survivors at all.

How sexual violence is charged in Yekatom and Ngaïssona cases

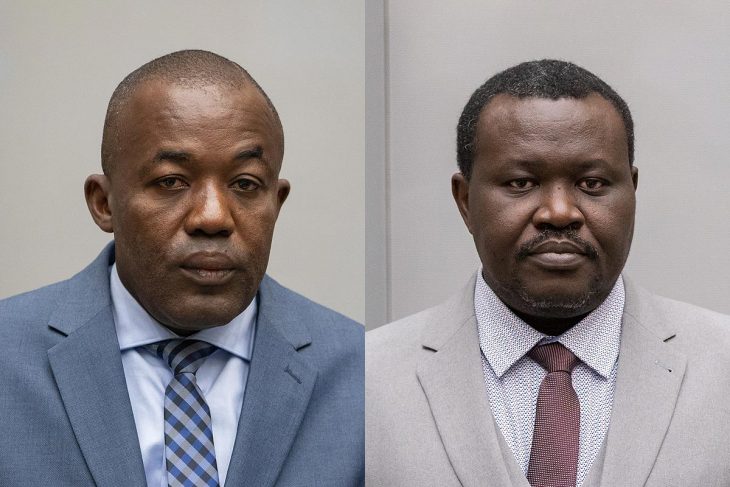

In October 2019, the ICC charged two anti-Balaka commanders with war crimes and crimes against humanity: Alfred “Rombhot” Yekatom and Patrice-Edouard Ngaïssona. Yekatom was a former Corporal in CAR’s armed forces who formed an anti-Balaka group after the Séléka, a politico-military coalition, successfully deposed former President François Bozizé in 2013. Patrice-Edouard Ngaïssona, once a member of Bozizé’s cabinet, was the former National General Coordinator of all anti-Balaka groups. The ICC’s case, known as CAR II, alleges that Ngaïssona – in coordination with Bozizé in exile and Yekatom in Bangui, among others – operated a “strategic common plan” to mobilize anti-Muslim sentiment and existing self-defense groups, who later came to be known as anti-Balaka, against Séléka militias to reclaim Bangui from Séléka president Michel Djotodia. In other words, the ICC has charged Yekatom on the basis of command responsibility for violence in Bangui and prefectures to its West whilst charging Ngaïssona with individual criminal responsibility for contributing to and commissioning violence perpetrated by all anti-Balaka groups throughout CAR.

CAR II presents a dynamic case study to explore why the ICC’s justice in CAR might be best described as phantom justice. Although the ICC charged Ngaïssona with six counts of rape as a war crime and crime against humanity in the Ombella-M’Poko and Lobaye Prefectures, they did not charge Yekatom, who was the zone commander in those prefectures, with rape. Human Rights Watch, among other human rights groups, has documented acts of SGBV perpetrated by Yekatom’s group. The ICC’s recent Confirmation of Charges hearing made reference to testimony by 83 forcibly conscripted children – a crime for which Yekatom has been charged – on the widespread and systematic SGBV they faced. Given this, survivors are left to wonder why only the political coordinator rather than a commander faces charges of rape.

The broken link of command responsibility

The ICC operates on the principle that only some are “most responsible” for atrocity, selecting only high-level commanders against whom to bring charges. Article 25 of the Rome Statute establishes that an individual is criminally liable for crimes they ordered, facilitated or to which they intentionally contributed through a group’s common purpose. Article 28 goes further, stating that a commander is additionally criminally liable for crimes perpetrated by forces under their effective authority when they knew or ought to have known and failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures to prevent or repress criminal acts. These commanders are held criminally liable for crimes, in which they may not have directly participated, on the basis of command responsibility – they are effectively treated as a proxy for the significant number of perpetrators on the ground.

Within this framework, CAR II could find Ngaïssona individually criminally responsible for SGBV under Article 25 and Yekatom additionally responsible as a commander under Article 28. Yet the recent acquittal of Jean-Pierre Bemba Gombo for crimes perpetrated during Bozizé’s 2003 coup revealed just how complicated it is to hold a commander accountable for exercising control over his forces under Article 28. The ICC’s first case in CAR, known now as CAR I, charged Bemba on the basis of command responsibility for rape perpetrated by his forces hired to defend Patassé’s government. The ICC Trial Chamber in CAR I initially determined that Bemba’s command responsibility was a form of liability for the failure to exercise control and thus amounted to participation, rather than a separate offense of commission.

Two years after Bemba was convicted, the Appellate Chamber concluded that Bemba’s status as a remote commander and a minimal effort to take reasonable measures to repress criminal acts extinguished his responsibility. In effect, the CAR I Appellate Chamber broke the link between the power a commander holds over subordinates and their responsibility to wield that power to control their forces. CAR I has effectively carved out a shield for commanders who operate from a distance, exactly as Ngaïssona did, to wield when facing demands for accountability. In CAR II’s context, the link between those who have power and necessarily exercise authority over their militias and are therefore also responsible for the actions of those forces is already a tenuous connection. As a result, even as the ICC determines justice has to be done, it also legitimates the very notion that responsibility is an optional requirement to holding authority.

Sexual violence victims: Justice for whom?

The CAR I acquittal has significant political implications for conditions on the ground and for the prospects of justice in CAR II. In centring international justice around only the few who are most responsible, the acts of sexual violence that matter to the ICC are also limited. CAR I and CAR II demonstrate key problems in how the ICC understands the nature of the violence in the Séléka/anti-Balaka conflict and how it relates to victims. CAR I used a definition of rape that did not depend on a victim’s lack of consent, but rather proving the “physical invasion.”

Such an approach attempts to contextualize and un-gender SGBV, but the effect was to reduce the type of testimony the Court was willing to hear about SGBV in CAR writ large. As a result, women and girls only accounted for 39 of the 1,051 victims whose testimonies were approved. From the investigation to trial stage, 40% of the testimony about sexual violence was excluded because judges concluded the evidence was redundant. Acts of SGBV that did not constitute rape were subsumed by other charges in CAR I, including “outrages of personal dignity” or “torture,” which themselves were excluded from the trial. In CAR II, acts of sexual violence that do not constitute rape are subsumed by the crime of “persecution.” The ICC’s practice renders countless acts of atrocity immaterial and excludes survivors of SGBV, after they re-live the violence through testimony for the sake of justice. This practice establishes a sliding scale for victims’ participation: only those victims who are willing to give testimony to the violence they survived to the Trial Chamber’s satisfaction are allowed to participate in the ICC’s justice.

Put simply, the ICC’s practice has placed Central Africans at a great deal of risk precisely because CAR remains a phantom state. SGBV is a highly visible and public form of violence in CAR, but most survivors don’t tell anyone what has happened to them. Silence amplifies the violence of SGBV. To choose to give testimony before the ICC only to be dismissed does just as much, perhaps more, damage to survivors seeking justice. A responsibility to punish notwithstanding, the ICC, practitioners and scholars of transitional justice carry a distinct obligation to survivors of SGBV to create spaces for truth-telling and reconciliation precisely because those crimes persist well past ceasefires, peace agreements and prosecutions.

Considering the case of CAR, it remains critical to point out that, try as they might, liberal institutions of the West struggle to actually “do” justice – in CAR and elsewhere. It is therefore critical to recognise the limitations of the ICC approach in CAR II to determining who is ultimately responsible for mass violence, particularly where local processes are slow to investigate and prosecute.

OXFORD TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

OXFORD TRANSITIONAL JUSTICE RESEARCH

This article has been published as part of a partnership between JusticeInfo.net and the Oxford Transitional Justice Research (OTJR), a network of high-level transitional justice researchers which is part of the University of Oxford. Justiceinfo.net publishes OTJR publications under the joint responsibility of its editor and OTJR.

Megan Manion is a political scientist with an M.Sc. in the Politics of Conflict, Rights and Justice from SOAS, University of London, specialising in conflict and post-conflict transition, particularly peace, justice, truth and reconciliation. Her research explores the theory and practice of transitional justice, focusing on constructions of power and agency in the afterlives of colonialism, mass violence and transitional justice mechanisms.

Megan Manion is a political scientist with an M.Sc. in the Politics of Conflict, Rights and Justice from SOAS, University of London, specialising in conflict and post-conflict transition, particularly peace, justice, truth and reconciliation. Her research explores the theory and practice of transitional justice, focusing on constructions of power and agency in the afterlives of colonialism, mass violence and transitional justice mechanisms.