Is it a lack of will or a lack of means? Belgian investigations into the case of Martina Johnson, a Liberian suspected of having been commander in a major armed faction during the Liberian civil war, is worryingly slow, and many fear the consequences for the trial that is expected to take place.

Alain Werner, director of Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima which investigated Martina Johnson’s alleged crimes in 2011, regrets the death of a witness he considers key, and fears that others will die.The suspect’s lawyer, Jean Flamme, also says certain witnesses he wanted to interview for the defence are now dead. Meanwhile, he says Martina Johnson, 50, has been subject to strict rules of house arrest for the last six years and is suffering from a serious liver disease.

Johnson is suspected of having herself killed, tortured and maimed several people at a military checkpoint at the Dry Rice Market on the edge of the city.

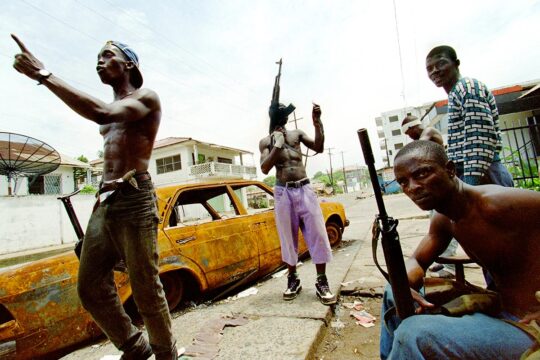

Martina Johnson is suspected of having served as a commander in the National Patriotic Front of Liberia, a rebel group led by Charles Taylor that sparked Liberia's first civil war between 1989 and 1996. The rebels launched an assault on the capital city of Monrovia on October 15, 1992, known as Operation Octopus, which claimed the lives of hundreds of civilians and members of foreign humanitarian organizations. Johnson is suspected of having herself killed, tortured and maimed several people at a military checkpoint at the Dry Rice Market on the edge of the city.

French and Finns go to Liberia, not the Belgians

After the fall of Charles Taylor in 2003 (he became president in 1997, before being forced by a new armed rebellion to flee the country), Martina Johnson went to Belgium. She settled in Ghent with her husband, a Belgian of Liberian origin, and their son. It was there that the police came to arrest her on 17 September 2014. Two years earlier, three Liberian victims had filed charges against Johnson for acts she allegedly committed during the assault on Monrovia.

Why has the investigation not yet been concluded? "The rogatory commission has not yet been able to go to Liberia. We are waiting for a positive message from the competent Liberian authorities," replies the Belgian Federal Prosecutor's Office, which says three requests to investigate at the scene of the crimes have been sent to the Liberian authorities and have remained unanswered.

It is therefore incomprehensible that the Belgian judicial authorities are unable to obtain authorization [to investigate in Liberia].

But Alain Werner, whose NGO has helped victims bring this and other cases linked to crimes committed during Liberia’s two civil wars (1989 to 2003), finds this argument hard to understand. "Indeed, things were blocked until last year. Liberia had not acceded to requests from foreign authorities to come and investigate in the country. But the situation has changed since 2019,” he says. “The French, the Finns and a third European country have received authorization to go to Liberia, and have already gone there. It is therefore incomprehensible that the Belgian judicial authorities are unable to obtain authorization, when the indictment of Martina Johnson dates from 2014, before investigations started in those other three countries.

“The impression we have from our investigative work in Liberia is that Johnson's crimes are known in Monrovia,” continues Werner, who has acted as prosecutor and counsel for victims in several international war crimes trials. “So if the Belgian investigators go there, they will find much more than we did at the time under more difficult conditions."

Defence demands

Johnson’s lawyer also thinks for different reasons that the investigators should travel to Liberia. "My client denies that she was in the military, but it's true that she was one of the security officers who were responsible for the close protection of Charles Taylor," says Flamme. "We are faced with written testimonies [brought via Civitas Maxima and its Liberian partner, the Global Justice and Reseach Project] from people who were children at the time of the events. They say they recognized Commander Martina Johnson. I highly doubt that. How do they know it was Martina Johnson? These witnesses need to be heard directly, in person.

"There is also a photographer who took a picture of a woman sitting on a cannon, claiming that it was her [Martina Johnson] and that she was an artillery general in Taylor's army,” continues the lawyer, who has already asked several times for his client's case to be dropped. “We obtained authorization four or five years ago to hear defence witnesses, but that required a trip to Liberia. First we were told it was impossible to go there because of the Ebola virus. Then one of the federal prosecutors told a hearing [in the Ghent indictment chamber] that there was no money to go there. Now, four or five of the witnesses who were asked to testify have died. The damage is irreparable. And we're getting to the point where it is no longer a reasonable time before trial."

Investigating nonetheless

Lawyer Luc Walleyn, who represents the civil parties, is nevertheless optimistic. "The contacts between the Belgian and Liberian authorities seem to be changing since these other European countries last year obtained authorization to carry out rogatory commissions on Liberian territory," he explains. "And other important investigative duties have nevertheless been carried out. The investigation is continuing, at its own pace." He nevertheless hopes the investigation will be completed by the end of 2020, at the latest. Walleyn notes that Liberian exiles and refugees have been heard in other countries. The federal prosecutor's office also says Belgian investigators have travelled to the United States to consult records from the Liberia Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Between 2006 and 2009, the Commission gathered some 20,000 testimonies of abuses committed during the armed conflict that ravaged the West African state. According to the NGO TRIAL International, Martina Johnson's name appears on the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's list of the main alleged perpetrators of these crimes.

Yet given the initiatives taken by other European courts handling Liberian cases, it seems Belgian judicial authorities can hardly avoid travelling to Monrovia to gather direct testimony, almost 30 years after the events. The current health crisis due to the coronavirus is likely to complicate such a visit a little more.