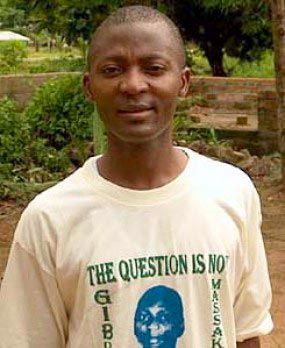

March 3, 2003 and in a bar on sumptuous Lumley beach overlooking Freetown’s spectacular peninsula, Gibril Massaquoi seems nervous. He has arrived an hour late to our meeting, leaving his transistor radio on and cocking his ear nervously for each news bulletin. The former Sierra Leonean rebel asserts he has a “clear conscience” but also says he fears arrest by the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), a court set up by the United Nations with the government’s accord to judge those most responsible for crimes committed in the civil war from 1991 to 2002.

Six days later comes the first wave of arrests. Massaquoi is questioned along with two other former top commanders of the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) ex-rebel group. It is a façade. In reality, it is Massaquoi who has delivered his two former comrades Issa Sesay and Morris Kallon into the hands of the SCSL prosecutor. He has been collaborating with the court for several months and has become its “top grass”, as a former prosecutor once said. He has recorded dozens of hours under questioning, recounting the war, how the RUF operated, its links to Liberian president at the time Charles Taylor and some of his lieutenants, their arms and diamond trafficking. Sesay and Kallon are imprisoned. Several years later they will be convicted and given heavy sentences. As for Massaquoi, he benefits from a guarded residence and dedicated attention from the services of the SCSL’s prosecution and witness protection offices. He is the main insider informing Sierra Leone trials. He testifies for the prosecution. Then in August 2008, with his task complete, he is discreetly sent to Finland with his wife and children, escaping any prosecution for the crimes of which numerous witnesses have accused him.

Massaquoi was soon employed by the rebels to keep a stockpile of weapons and ammunition. He rose rapidly in the ranks. A year later, from mid-1992 to the end of 1993, he led a group of about 100 men.

The early days of a “lord of war”

Massaquoi was 21 years old when, in March 1991, the RUF entered Sierra Leone from Liberian territory. In Liberia, the civil war had already been raging for 15 months, with all its atrocities, its murderous madness and its thousands of child soldiers. This is where the RUF had trained and armed itself. The RUF offensive launched ten years of civil war in Sierra Leone.

Massaquoi was at that time teaching at St. Paul's High School in the town of Pujehun, in southern Sierra Leone. In May, RUF rebels entered Pujehun. Massaquoi fled to a village about 10 kilometres away. Then he returned to the town, where he was soon employed by the rebels to keep a stockpile of weapons and ammunition, before undergoing three weeks of military and ideological training. He rose rapidly in the ranks. A year later, from mid-1992 to the end of 1993, he led a group of about 100 men, the Alligator Forces. At the end of 1993, he met Foday Sankoh, founder and leader of the rebellion. Massaquoi continued to rise in rank. He became commander of a battalion of about 400 men. In mid-1994, he became a captain, according to the often fantasist promotions granted within the armed movement.

But it was really in 1996 that he came out of the shadows. He accompanied Sankoh to Côte d'Ivoire to sign the first peace agreements between the rebellion and the civilian government. Massaquoi became spokesman for the RUF. He was at Sankoh’s side, now his "special assistant", when the RUF leader was placed under house arrest in Nigeria. He had the rank of major when, on 25 May 1997, a military coup in Freetown overthrew the government democratically elected a year earlier, annihilated the peace agreement and sealed the alliance between those who drenched the country in blood from 1991: the Sierra Leone Army and the RUF.

Suspected of treason

On August 2, 1997, Massaquoi landed in the Sierra Leonean capital. He was appointed member of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council, the AFRC, the new junta installed by non-commissioned officers. Massaquoi was one of the representatives of the RUF. In October, however, he was arrested by his comrades on suspicion of treason. In mid-February 1998, the West African intervention forces gained control of Freetown and re-established the civilian government. They found Massaquoi in the central prison and kept him there, again for treason, but against the civilian government. He was acquitted, but he was still there on January 6, 1999, when his former AFRC comrades led a lightning assault on Freetown. The attack was dubbed "Operation No Living Thing". The capital was set ablaze with fire and blood, marking the height of violence and cruelty in this conflict.

The attackers, after invading two thirds of the peninsula, were quickly pushed back. But Massaquoi, like all those incarcerated in the central prison, regained his freedom. He resumed his career as a rebel.

In the midst of the official disarmament phase, RUF commanders took some 500 UN peacekeepers hostage. For the international community, this was too much. The hostage crisis was to sign the death warrant of the RUF.

Endgame for the RUF

New peace agreements were reluctantly signed in July 1999 in Lomé, Togo. They provided the RUF with political legitimacy. Sankoh and a few other members of the rebellion settled in Freetown and entered the government. A large UN force was sent to ensure the expected transition to peace. Massaquoi was still at Sankoh's side, holding the rank of lieutenant colonel. The RUF appeared to be winning the day.

That was until that crucial first week of May 2000, when, in the midst of the official disarmament phase, RUF commanders took some 500 UN peacekeepers hostage. For the international community, this was too much. Public opinion in Sierra Leone was definitively turning against the duplicity of the RUF leader and against this rebellion which had never been popular. The hostage crisis was to sign the death warrant of the RUF.

Massaquoi was in the company of Sankoh when his residence was surrounded by a mixture of civilians, traditional hunters and soldiers. Several civilians were killed in a brutal exchange of fire. Massaquoi, one of the two men in charge of the residence security, managed to escape. Sankoh was captured. He was to die in prison three years later, before he could be tried by the SCSL. In one year, a strong foreign intervention would defeat the RUF. In January 2002, the Sierra Leonean civil war was officially over.

Massaquoi had the dubious privilege of having been a member of both the RUF and AFRC, the two armed factions that, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, are responsible for more than 70% of the abuses documented. He was expected to stand trial and he knew that. But he still had one card left to play: to cooperate with the prosecutor.

International prosecutor’s chief informer

And so came the time for justice in Sierra Leone. Two institutions worked concurrently: a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which operated between 2002 and 2004 and produced an extremely valuable report on the causes of the conflict, its conduct, its actors and the multiple and serious human rights violations that accompanied it; and a Special Court, established by the United Nations in agreement with the government, to try "those who bear the greatest responsibility" for the crimes.

Massaquoi had the dubious privilege of having been a member of both the RUF and AFRC, the two armed factions that, according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, are responsible for the largest share of crimes committed - together, more than 70% of the abuses documented. He was expected to stand trial and he knew that. But he still had one card left to play: to cooperate with the prosecutor.

It was the American Alan White, head of Investigations at the new Special Court, who met him shortly after his arrival in Sierra Leone in mid-2002. There was no shortage of former combatants willing to testify and cooperate. Massaquoi was immediately more cooperative than the others. He had dealt directly with Sankoh, with former Liberian president Charles Taylor, whom the prosecutor wanted to indict, and with his RUF link, Benjamin Yeaten, who was also of interest to the investigators. Massaquoi had information seriously implicating them in the trafficking of arms and diamonds. He knew by heart the structure of the RUF as well as those responsible for crimes committed by both the RUF and the AFRC. Massaquoi also served the court by recruiting other insiders.

According to members of the prosecutor's office, he was not among those "bearing the greatest responsibility" for the crimes, the official criterion for selecting individuals to be prosecuted. "As far as I know, it was Massaquoi who contacted Al White to meet him. He told us everything and agreed to collaborate with us. The Chief Prosecutor said yes and granted him immunity. In Liberia, we focused our investigation on Taylor. Never once did the name Massaquoi come up in that investigation," says Gilbert Morissette, who questioned Massaquoi at length.

According to the Commission, he "personally fuelled the tensions surrounding the UNAMSIL hostage-taking crisis. He was a central part of the chain of command of the RUF. Massaquoi bears an individual share of the responsibility for the deterioration in the security situation in Sierra Leone".

The Truth Commission’s accusations

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission thought differently. It noted that Massaquoi – who testified to the Commission – was among the ten members of the RUF high command and said this personal assistant to the group’s founding leader was “influential”. The Commission “holds Gibril Massaquoi responsible for the torture and summary executions of up to 25 RUF members in the Pujehun District in 1993”, it said.

Massaquoi's role in the hostage-taking of UN peacekeepers (UNAMSIL) is also highlighted. According to the Commission, he "personally fuelled the tensions surrounding the UNAMSIL hostage-taking crisis. He was a central part of the chain of command of the RUF. He was duplicitous in his presentation of the RUF position to the outside world. Massaquoi bears an individual share of the responsibility for the deterioration in the security situation in Sierra Leone". For the commissioners, the duplicity of Massaquoi, convinced that he could overthrow the civilian government including by force of arms, was total.

An elegant, intelligent “killer”

The Commission explained it treated the former rebel’s testimony “with extreme caution”. “Massaquoi was unique in the RUF in that he remained an enigma to many of those around him throughout the war. He was well-educated and therefore able to pass himself off as an ‘administrator’ to the outside world.”

According to the Commission, Massaquoi evaded questions about his own role in military operations. Yet, it adds, numerous testimonies from his former accomplices establish that he "fought fiercely at the front line", commanding units during "vital military operations". The analysis is implacable: "In the prosecution of military and political strategy after Lomé [peace accords], Massaquoi was Sankoh's 'Special Assistant' in every sense. His position was the closest to a de facto second-in-command."

Lansana Gberie, a renowned expert and author on Sierra Leone and Liberia (and Sierra Leone's ambassador to Switzerland and the UN in Geneva since 2018), met with Massaquoi many times in Freetown while he was under the protection of the court. He describes him as follows: “He was one of the very few who was literate. He was handsome, very smooth, intelligent and articulate. He looked smart and clean. He would talk about others, not about his own role as a brutal person. [But] he was very brutal and he definitely killed people. There is no way he would have raised at that level without being a participant. I don’t buy that. He was a killer but it was difficult to see it as a person.”

In such investigations, “you can’t prosecute everybody”, explains Alan White, former head of investigations at the SCSL. “He helped us identify the targets. The value of the information was so significant that we could verify it.”

The SCSL’s most precious informer

In such investigations, “you can’t prosecute everybody”, explains Alan White, former head of investigations at the SCSL. “He helped us identify the targets. The value of the information was so significant that we could verify it.” Massaquoi was the UN court’s most precious informer. He was more important than Mike Lamin, another top RUF member who also worked with the prosecutor, perhaps under Massaquoi’s influence. “Massaquoi was the most important of all,” says Morissette. “To me he was probably the most important one,” confirms White.

In October 2005, Massaquoi testified in the trial of three former AFRC leaders. He did so publicly, without masking his identity or face, even though he was a protected witness. This was unusual for a witness of his status. In 2007, under the escort of the special court, he was in Chicago to testify against a Liberian who fought in Liberia and Sierra Leone and was accused of torture and violating immigration laws.

A “respectable life” in Finland

And so in August 2008, he left for Finland to start a new life in the industrial university city of Tampere. Massaquoi started learning Finnish at university. The Center for Peace and Conflict Research invited him to participate in its seminars and to speak there, without really knowing who they were dealing with. In one of these workshops, in 2010, he was identified as a "coordinator". He apparently spoke very little about his past or his role in the trials in Freetown. According to a member of the university who wished to remain anonymous, he led "a respectable life".

During this period, he submitted a manuscript to the expert eye of Lansana Gberie, who shared it with Stephen Ellis, one of the most renowned scholars on these conflicts in West Africa in the 1990s and an expert witness before the Special Court. Already in 2005, when he testified in court, Massaquoi said he had written 500 pages on the conflict. But “his manuscript was useless”, says Gberie. “It was full of embellishments and outright lies to make him appear heroic.”

Massaquoi did not arrive in Finland as a "protected" witness but as a "relocated" witness. By appearing and speaking under his real name in public events, particularly at university, some people considered that the Sierra Leonean had, in effect, waived any possible right to protection.

Civitas Maxima’s investigation

It was in 2018 that, on the basis of an important initial testimony, the Swiss NGO Civitas Maxima which for several years had been investigating Liberians suspected of serious crimes during the two Liberian civil wars, decided to deepen its research on the alleged role of Massaquoi in Liberia, as opposed to Sierra Leone. It focused especially on the period 2001-2002, between the end of the fighting in Sierra Leone and his collaboration with the Special Court, a period during which the second Liberian civil war was raging.

The NGO discovered facts of a magnitude and nature that go to the heart of the organization's mandate, according to its director Alain Werner, who is particularly familiar with the case. From 2003 to 2008, Werner worked in the office of the prosecutor of the Special Court in Freetown. The fact that Massaquoi's presence in Finland was publicly known and revealed on the Internet seemed to remove the obstacle of witness protection. Indeed, according to Finnish judicial sources, Massaquoi did not arrive in Finland as a "protected" witness but as a "relocated" witness. At the time, Finland did not have a national witness protection programme. By appearing and speaking under his real name in public events, particularly at university, some people considered that the Sierra Leonean had, in effect, waived any possible right to protection.

In August 2018, Civitas Maxima informed the Finnish judiciary of its research. In October, the Finnish public prosecutor gave a green light to the investigation. In Finland, explains Thomas Elfgren who is leading the investigations in this case, bilateral agreements are not binding on the public prosecutor in criminal matters. If there is reason to believe that a national or permanent resident has committed crimes, there is an obligation to investigate. “We have very strict standards. If an individual has committed crimes, he cannot be given immunity. We are obligated by law to look into the case,” he explains.

Why would Massaquoi have continued to go and get his hands dirty in Liberia when he could slip away and extricate himself from ten years of war by keeping a low profile in Sierra Leone?

Controversy over the Finnish investigation

At the end of 2018, the Finns contacted representatives of the Special Court. Officially, the SCSL had closed, but as with all international tribunals that have completed their work there is still a "residual mechanism" in place to manage a number of ongoing tasks, such as requests for the early release of convicted persons or witness protection. According to several sources, the representatives of the Mechanism expressed their concern. But the Finns replied that their investigation did not touch on the mandate of the Special Court since the alleged facts took place in Liberia, whereas the Special Court only had jurisdiction over crimes committed in Sierra Leone.

In 2019, Finnish police officers visited Liberia three times. They gathered more than 90 testimonies that convinced them they had a solid case. According to several sources, with the agreement of the Mechanism they also interviewed at least three of the individuals whom Massaquoi helped convict and who are currently serving their sentences in a prison in Rwanda.

There is controversy among Massaquoi’s protectors, supporters of the lawsuit and experts about the credibility of the allegations against him. Why would Massaquoi have continued to go and get his hands dirty in Liberia when he could slip away and extricate himself from ten years of war by keeping a low profile in Sierra Leone? “It doesn’t make sense to me, from a probability point of view,” says Lansana Gberie. “In 2001-2002, he had fallen out with his friends because of money. He was finding a way out. I wouldn’t think a guy like this would be stupid enough to go back to Liberia. But maybe, who knows? Some RUF guys went to Liberia, a bunch of them. He might have been among them. He knows Liberia quite well. I don’t know. I would like to see what they found.”

The Massaquoi case was born, shaking up the international legal community: Can we and should we prosecute a former "insider" who helped a UN court?

Trafficking and serious crimes

There are some public indications of his presence in Liberia. In October 2001, a report by the UN Panel of Experts on Liberia noted that the relationship between the RUF and Liberia had continued, despite a split among Sierra Leonean rebels between those embracing disarmament and those willing to continue fighting. RUF units were then fighting in parts of Liberia, the experts note. They also reveal that in August 2000, police were surprised during a raid on a Lebanese businessman's home to find Massaquoi with a bag containing $15,000. They mention another incident, dating from July 2001, when the same Massaquoi filed a complaint for having been swindled in the purchase of 69 vehicles for the RUF, after giving $110,000 in cash and 2,600 carats of gold. The presumed origin of the money was the diamond trade from Sierra Leone.

But in Finland, Gibril Massaquoi is accused of far more serious and numerous crimes: crimes against humanity and war crimes, including for murder, torture and rape. On March 10, 2020, seventeen years to the day after he shamelessly put his former rebel friends in the hands of international justice, Gibril Massaquoi was in turn picked up by a national police force denying him any special status. The Massaquoi case was born, shaking up the international legal community: Can we and should we prosecute a former "insider" who helped a UN court?

WANT TO LEARN MORE?

THE MASSAQUOI AFFAIR: SPECIAL REPORT ON THE JUDAS OF SIERRA LEONE (PART 2)

Gibril Massaquoi, the main informer for the prosecutor of the Special Court for Sierra Leone (SCSL), was arrested in Finland on 10 March. This is the first time that a UN court "insider" has been prosecuted by a national court without prior agreement. And this sows discord between former members of the SCSL. Should it be criticized? Were the dice loaded from the start? Here is the second part of our exclusive investigation. [READ MORE]

TIMELINE

December 1989: start of the first civil war in Liberia (1989-1996), launched by Charles Taylor.

March 1991: start of the civil war in Sierra Leone, launched by Foday Sankoh’s RUF.

April 1992: Military coup in Freetown. First military junta of the NPRC.

March 1996: The NPRC military junta is replaced by an elected civilian government.

November 1996: First peace accord in Abidjan.

May 1997: Military coup. Second military junta of the AFRC.

July 1997: Charles Taylor elected as president of Liberia.

February 1998: Civilian government restored to power in Sierra Leone through force or arms.

January 1999: Invasion of Freetown by former members of the AFRC.

July 1999: Second peace accord reached in Lomé.

May 2000: 500 peacekeepers taken hostage by the RUF. Sankoh is arrested in Freetown.

May 2001: The RUF disarms.

January 2002: Official end of the civil war in Sierra Leone. The UN sets up a Special Court.

2003: Hearings before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission; first arrests by the SCSL; Charles Taylor goes into exile; end of the second Liberian civil war (1999-2003).