A political earthquake is rumbling through Ivory Coast. On April 28, an Ivorian court found Guillaume Soro, a hopeful in the October presidential election, guilty of embezzlement and money laundering. The 48-year-old former rebel commander-in-chief was sentenced to 20 years in jail.

The political dimension of Soro’s conviction was not lost on Ivorian citizens. They have watched his rise to power over the past two decades. But his presidential ambitions largely explain his judicial downfall. Soro’s conviction can be understood as the latest chapter of a power struggle that began to unravel since president Alassane Ouattara’s re-election in October 2015.

Several pointers appear to corroborate the suspicion that Soro’s prosecution was politically motivated. His arrest warrant was made public when it was known to all that he was in Europe, providing a compelling reason for him not to return home. The charges filed against him include conspiracy to overthrow sitting president Ouattara.

The decision to proceed against him in absentia, alongside other concerns about due process, suggests that the government’s main intention was to keep him at bay, not in custody. Overall, many Ivorians see Soro’s conviction as an attempt to exclude him from the presidential elections scheduled for late October. This would pave the way for the election of Ouattara’s favourite candidate and current prime minister, Amadou Gon Coulibaly.

Soro’s ascent to power

There are much wider implications to these developments too – what Soro’s conviction means for international criminal justice. Two interrelated questions stand out. Why did Soro fall from grace in the first place? And does his demise provide the International Criminal Court with a second – and arguably undeserved – chance to deliver justice for atrocities perpetrated during almost a decade of civil conflict in the West African country?

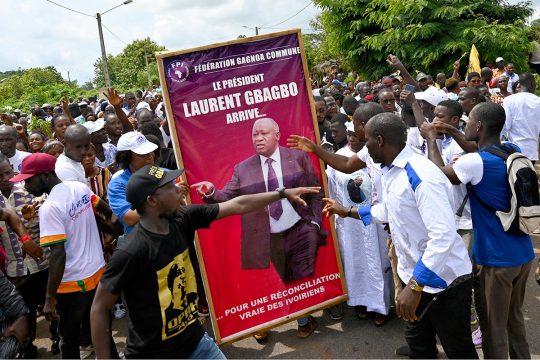

There is arguably nobody in Ivory Coast who contributed more to Ouattara’s ascent to the presidency than Soro. Soro was the commander-in-chief of the rebel forces that brought former president Laurent Gbagbo’s illiberal regime to an end. Soro’s military and political struggle to topple Gbagbo began with the failed coup of September 2002. It lasted until Gbagbo’s defeat and arrest in April 2011.

Ouattara felt understandably indebted to Soro and rewarded him generously. For this reason, he also turned a blind eye on the atrocities perpetrated by Soro’s rebels as they marched on Abidjan. But as time passed and the wartime loyalties faded away, Soro’s past became a political liability for Ouattara and a looming threat for Ivory Coast’s fragile democracy.

Still, Ouattara twice came to the rescue of his former ally. His government refused to comply with two arrest warrants against Soro. One was issued by a French judge in December 2015. The other was requested by the government of neighbouring Burkina Faso in January 2016.

The falling out

Attitudes towards Soro began to change in late 2016, when Ouattara took institutional, political and judicial steps to distance himself from his former ally. Even the adoption of the new constitution, which established the position of vice president and added an upper chamber to the unicameral national assembly, provided an occasion to weaken Soro’s grip on power.

But it was Soro’s suspected involvement in the mutinies of January and May 2017 that marked the point of no return. Now he was perceived as a threat to the Ivorian state, Soro’s finances and ties with wealthy benefactors suddenly came under close scrutiny by the national judiciary.

Unwilling to accept Ouattara’s proverbial olive branch and endorse his handpicked successor, Soro cut all remaining ties with the president. He resigned from the national assembly speakership and from his party in February 2019. It was then that Soro, no longer under Ouattara’s patronage, became a viable target for international prosecution.

A test for the credibility of the ICC

Having Soro prosecuted in The Hague is certainly appealing to the Ouattara government. A domestic trial would be politically costly. And, given Soro’s popularity and influence over the military, likely conducive to civil turmoil.

At the same time, recourse to international justice is not fail-proof either. The gross mismanagement of the case brought against former president Gbagbo and Charles Blé Goudé is still fresh in the memory of many Ivorians. It led to their acquittal in January 2019. It also served to undermine the credibility of the Hague-based tribunal.

Soro’s recent conviction offers an opportunity for improvement and redemption that the court cannot afford to pass. Apart from justice being done, bringing a case against Soro would also help address perceptions about the court’s impartiality – or lack thereof. It would be the first international prosecution targeting a high-ranking member from the “winning” side of the civil war. On this point, it is worth recalling that scholars and observers of Ivorian politics have lamented the Prosecutor’s silence regarding alleged crimes committed by pro-Ouattara forces.

Assuming International Criminal Court chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda’s office actually capitalises on this opportunity, how would Ivorian authorities react? Several cues suggest the Ivorian government wants the court to open a case against Soro, the sooner the better. Past interactions between Ivorian authorities and the Hague-based court may help make sense of why and how recent domestic decisions call for ICC scrutiny of Soro.

A double win?

Let us not forget that the Ouattara government surrendered both Gbagbo and Blé Goudé to the international court, in 2011 and 2013 respectively. When it refused to surrender Gbagbo’s wife Simone, the Ivorian judiciary charged her with war crimes, thus halting the ICC’s complementarity jurisdiction.

Soro too has been convicted for crimes that do not fall within the International Criminal Court’s subject-matter jurisdiction. There is nevertheless no worse country to be in than France for those who seek to escape international justice. For the past 25 years, French authorities have proactively investigated, arrested, and surrendered to international criminal tribunals suspects from numerous countries. These range from the Western Balkans to Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Chad, Central African Republic, Libya and Syria.

Lastly, an ICC prosecution has far-reaching political and personal consequences for defendants that may even outlast their acquittal. This was proven by the fact that Gbagbo and Blé Goudé have been unable to return home and resume their political careers pending appeal.

A case against Soro would be a win for both the Hague-based court, in dire need of a credibility boost, and the outgoing Ivorian administration, seeking to smoothly transfer powers to someone who will continue, rather than undo, Ouattara’s legacy.

What remains to be seen is whether Soro will accept his grim situation or fight to fulfil his dream of capturing the presidency of Ivory Coast by any means necessary.![]()

Marco Bocchese, Visiting Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Illinois at Chicago

This article, slightly modified by Justice Info with the agreement of the author, is republished from The Conversation under Creative Commons license. Read the original article.