On 9 June, there was shouting, singing and tears of joy in the al-Salam camp for displaced people near Al-Fashir, where almost 50,000 people have been waiting since 2005 for a chance to live decently in peace. Most had lost all hope of justice for the atrocities they have suffered since the outbreak of the war in Darfur in 2003.

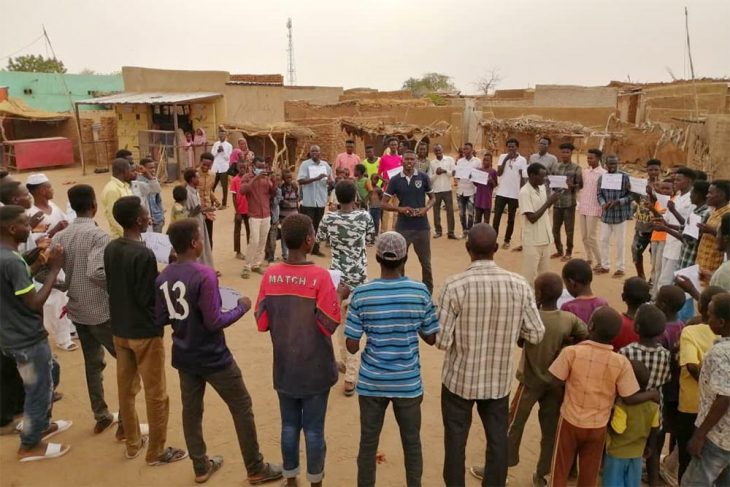

That Tuesday, when we called him on the phone, the voice of "Dozana" Mohamed Ibrahim, an English teacher in his late thirties, is joyful. At the same time, Ali Kushayb was on a military plane chartered by France that took off from Bangui, Central African Republic, for the International Criminal Court (ICC) jail in The Hague, Netherlands. Thirteen years after the ICC arrest warrant for him, 17 years after the first crimes of which he is accused, "everyone in the camp is following the progress of the plane to The Hague!” Dozana tells us. "We have been waiting for this moment for so long. He's the first one who will be tried, and that means there is rule of law, that there will be no more impunity!" Around him, dozens of young men are holding A4 sheets of paper on which are written "we are with the ICC" or "Kushayb, go to hell".

"A herder like any other"

The name of Ali Mohamed Ali Abd Al Rahman, alias Ali Kushayb, was added to the ICC's list of wanted persons on 27 April 2007. In western Sudan, he was known and greatly feared by villagers in south and central Darfur as of 2003. He belongs to the Ta'esha tribe, a branch of the Baqqara, semi-nomadic pastoralists who define themselves as "Arab" rather than the "black African" farmers with whom they are sometimes in conflict over land. Suliman Baldo, a Sudan specialist and advisor to the NGO Enough Project, describes the new ICC prisoner as "a herder like any other. He belongs to his tribe's paramilitary organization, which protects cattle herds from wild animals and thieves”.

The conflict in Darfur turned into a war. In February 2003, an insurgency began in the region of the Jebel Marra volcano, led by the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA), which includes members of the Fur, Massalit, Zaghawa and Berti ethnic groups. These "African tribes" blamed the central government for years of neglect and, above all, a lack of protection against the growing number of attacks by the "Arab tribes". In April, the SLA entered Al-Fashir and seized the airport. In Khartoum, Omar Al-Bashir decided to suppress the insurgency. The governor of North Darfur enlisted and armed Janjaweed militiamen from Arab tribes.

Rebellion and ethnic cleansing

Ali Mohamed Ali Abd al-Rahman was one of them. He distinguished himself by his fighting spirit and became Ali Kushayb, head of a Janjaweed unit. “The militias were not integrated into the Sudanese army," says Baldo. “They were based on ethnic unity and only ethnic unity, and had their own structures. But they were sometimes supported on the ground by the national army and by the Sudanese air force. They were the proxy forces." These forces attacked civilians in a deliberate policy of ethnic cleansing, according to several international inquiries. "It would appear that those who planned and organized the attacks on the villages were intent on driving the victims from their homes, mainly for the purposes of counter-insurgency warfare," wrote the 2004 International Commission of Inquiry mandated by the UN Security Council and chaired by Professor Antonio Cassese.

Three years later, the ICC issued an arrest warrant for Ali Kushayb for crimes against humanity and war crimes, including murder, deportation, torture, rape, persecution, intentional attack on civilians, looting and destruction. The arrest warrant states that he allegedly "conscripted, armed, financed and supplied" militiamen responsible for deadly attacks in 2003 and 2004 in Darfur.

"We all knew his name"

Guy Josif Adam, born in 1986 in a village near Jebel Marra and now a Harvard student of international law, remembers the Janjaweed attack on his locality. "It was a Monday in April 2004. I heard gunshots, I saw men in pickup trucks, on horseback and on camels," he says. “They set fire to houses, shot at people. I started running, I was wounded, but I managed to escape." He never saw his parents again. “I'm sure it was Ali Kushayb's men," he says. “He was very active in this area, we all knew his name.”

Witnesses interviewed by Human Rights Watch a few months later testify to Kushayb’s presence in March 2004 at massacres in Mukjar, Bindisi, Garsila and Deleig, four localities in Wadi Saleh, west Darfur. The ICC accuses him of having been the link between Janjaweed leaders and the government in Khartoum. He was never really worried by the Bashir regime. In 2006, Bashir came under strong international pressure to dismantle the Janjaweed. Kushayb was arrested and then released without charge. Some of these militias were integrated into the regular forces of the border guards, while another was integrated into the central police reserve, a unit that was in fact military. It is there that Kushayb was given a command post.

In 2013, the Misseirya were in conflict with the Salamat. The two "Arab" tribes were competing for land and resources that were all the more reduced because the central government, hit by economic crisis after the independence of South Sudan, was no longer funding them. Men from the central police reserve, in their uniforms and vehicles, lent a hand to the Misseirya. Kushayb, one of the leaders of this force made up of members of his Ta'esha tribe allied with the Misseirya, is widely blamed for command responsibility.

Kushayb feels safe even after Bashir’s fall

After Bashir’s fall in April 2019 and the establishment of a transitional government in September, the former Janjaweed leader lived untroubled in his home town of Reheid al-Birdi in south Darfur. Bashir, his former interior minister Ahmed Haroun and former defence minister Abdulrahim Hussein – all wanted also by the ICC -- were imprisoned in Khartoum. “Change has not reached the Nyala region of Darfur," says Baldo. “They are the same authorities as before, so Kushayb did not feel in danger.”

What changed, according to Baldo, was the announcement in February 2020 that the Khartoum government was ready to hand Bashir over to the ICC. The former militia leader no longer felt safe. The government did not follow up on its stated intention, but Kushayb preferred to leave Sudan and cross the border into the Central African Republic. This is where he finally surrendered voluntarily, according to an ICC communiqué. "He negotiated for a week and it was the Central African Prosecutor who picked him up in a helicopter of the UN force in the Central African Republic, MINUSCA," says Baldo.

“His transfer to The Hague is a very significant first step," Baldo believes. “It reinforces the legitimacy of the ICC and gives hope to the two million displaced Darfuris and refugees. All the more because his defence will certainly implicate the Sudanese army, saying Kushayb was obeying orders. That is his only possible defence." If the charges are confirmed, his could indeed embarrass certain high-ranking soldiers. These include General Abdelfattah Abdelrahman al-Burhan, current head of the Sovereign Council which is the highest transitional authority; and his number two Mohamed Hamdan Dagolo, known as Hemetti. Both men are suspected of having ordered atrocities in Darfur.

Twenty-four hours after Kushayb’s transfer to The Hague, the Sudanese authorities had not yet made any comment.