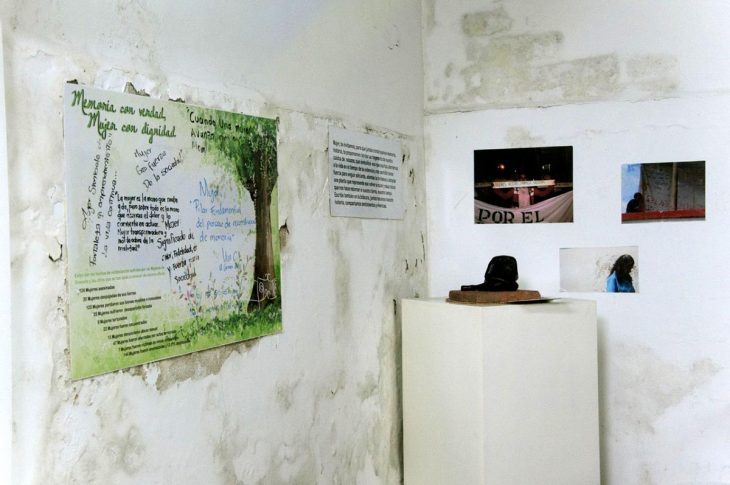

Two weeks ago, on a Saturday afternoon, Gloria Quintero arrived at the Hall of Never Again on a corner of Granada’s main square, 44 kilometers east of Medellin. The small memorial conceived and managed by local victims had been closed since late March due to the Covid-19 pandemic and strict national lockdowns, but Gloria wanted to take a take a few photos to share on social media to mark the International Day of Victims of Enforced Disappearance.

As she opened the door, she was stung by a terrible discovery: dampness was rampant on the first floor of the three-story adobe house. She approached the bookcase where they keep their most prized treasures: a series of black-sleeved booklets, each adorned with a photograph on the cover, where victims write messages for relatives who were murdered or are still deemed missing. Four of these ‘logbooks’, as they call them, were considerably damaged, their heartfelt letters transformed into crinkled pages and blurry blots of wet ink. Dozens more were stuck together by moisture and covered by fungus.

“I was overcome by pain, sadness and impotence”, says Gloria, one of the Hall’s volunteer caretakers since its birth in 2009. Her own family is represented there: her brother Rubén, disappeared by right-wing paramilitaries 18 years ago, is one of the villagers whose photo hangs on the gigantic mural and whose name adorns one of the 300 logbooks. Following the advice of a concerned museum curator, they laid them on cloth in an aired room, popsicle sticks and bond paper in between each sheet so as to absorb the remaining moisture – “first aid for archives”, in Gloria’s words. But they still need help in properly restoring them.

The water leak at the Hall of Never Again, one of Colombia’s best known memorials, underscores how many historical memory initiatives that are central to the aspirations of victims of Colombia’s 52-year-long armed conflict to truth and redress are floundering amid a lack of support from national and local governments. It is also symptomatic of a wider problem: even though the country has made significant strides in truth-seeking, it is struggling to preserve the memory produced by communities and victims.

A town’s pain and resilience

Tucked away in the mountains of north-western Colombia, Granada’s story has been mired by suffering, but it has also become an icon of reconstruction and resilience for the country that signed a landmark peace deal with the former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in 2016.

For years ravaged by left-wing FARC and National Liberation Army (ELN) guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries, at least 20.411 persons were forced to flee the town and its surroundings since 1985, meaning more than 90% of Granada’s inhabitants have been officially registered as victims of forced displacement. Its most painful chapters were only separated by one month in late 2000, when a massacre perpetrated by paramilitaries that killed 19 persons was followed by a FARC-led siege and a car bomb that left 28 dead and debris everywhere.

A few years later, hundreds of families started coming back, initially on their own and later on with support from the local administration of Medellín, the country’s second largest city where most had sought refuge. Those return programs inspired the landmark 2011 victims bill, which paved the way for the Colombian government to finally recognise victims of the armed conflict and design redress measures such as land restitution and state-accompanied returns. Granada became one of the vibrant laboratories of what Colombia’s post-conflict could look like if the country put an end to violence.

Two iconic images taken on the same day by Jesús Abad Colorado, Colombia’s best-known photojournalist, illustrate Granada’s will to forge ahead. On the morning of December 9th, 2000 he captured villagers amid the town’s ruins waving a gigantic flag declaring it a ‘territory of peace’, an image that years later graced the cover of the National Centre for Historical Memory’s exhaustive report on violence there. That afternoon, Colorado immortalized a couple entering Granada’s church to get married, an improbable gesture of hope in the midst of such despair. ‘In war we all lose. Let’s all help build a peace process’, read a sign next to them.

Seventeen years after the young couple’s wish, the once again tranquil rural outpost was the site – as JusticeInfo told – of one of the few public acts of contrition made so far by former FARC rebels. Although he did not address specific events, former FARC commander and peace negotiator Pastor Álape asked for villagers’ forgiveness and promised his organisation would provide truth regarding the 755 cases of forced disappearance identified there.

“People might think it’s just a book, but to me this is my father”

Few initiatives symbolise Granada’s will to forge ahead like the Hall of Never Again. Created by the town’s victims organised in Asovida, a local NGO, the memorial began attracting visitors from the region and even abroad. As many as a hundred visitors made the trip there every week up until the Covid-19 pandemic.

Ten years ago, on a suggestion made by a visual artist, they began writing about their deceased and disappeared loved ones. What began as a purely biographical exercise quickly evolved into something more powerful, as these notebooks became crowded with letters, poems, drawings, songs and dreams.

“When I heard about the leak, I felt like something had happened to my dad. People might think it’s just a book, but to me this is my father. It’s where I talk to him. Whether it’s something good or bad, he knows about it. Ever since I was seven, I’ve been writing him letters because I feel and trust that one day he will return and read all of them, and see how much I love him,” says Yesica Giraldo, a 19-year-old accounting assistant who lives in Medellín. Jair Giraldo, her father, disappeared on September 11th 2006, with FARC being the presumed perpetrator.

“To those who are no longer with us but live in our memories, this is a way of ensuring they are present. When you read the logbooks, these memories become tangible,” says Consuelo López, whose husband Humberto Ramírez was murdered in 2001.

Most townsfolk have forged very special relationships with these notebooks. “People speak of visiting them. One girl asks her father if a boy suits her and pleads for a signal. It’s as if these were material representations of their loved ones. There was a spontaneous process of turning them into a way of keeping in touch,” says Marda Zuluaga, a psychologist and professor at Eafit University who wrote her doctoral thesis on Granada’s logbooks and whose family originally hails from the town.

“The Hall is the result of granadinos’ conviction that, in order to overcome the crippling devastation and isolation imposed on them by the violence, communities of memory need to be constructed. In contexts of low-intensity but widespread conflict such as that of Colombia, communities of memory are essential to restoring social bonds and creating platforms for solidarity and action”, says Robin Greeley, an art historian and University of Connecticut professor who has also studied Granada’s process.

Treasures stored in a leaky home

Despite how valuable the logbooks are to Granada, the Hall of Never Again has struggled over the years to operate. Its leaders received the space within the town’s house of culture as a loan from the municipality, but don’t have the money needed to fix structural problems such as damaged gutters and leaky walls.

Gloria and her fellow volunteers warned of such problems since 2012, including when part of the ceiling collapsed during a flood. The mayor pledged 10.000 dollars to repair the old tile roof but never delivered, she says. They raised 1.500 dollars in a crowdfunding campaign in 2018, but used the proceeds to pay for other urgent expenses.

Their needs are not just financial. Even though they’ve received support from institutions like the University of Antioquia on managing their photo archive and creating an educational toolkit for visitors, they still lack the know-how to preserve their documents in optimal conditions, keep their accounts in order and even draft project proposals they can submit to international aid agencies. They especially deplore the absence of state support, whether it’s from local or national authorities. “If we’d been among their priorities, this wouldn’t have happened,” Gloria says.

The emergency did spark a flurry of promises. Antioquia’s governor visited on September 10, signing a written pledge to fund the house’s repairs, send a team of engineers to inspect the damages and help restore the logbooks. The mayor promised to share the costs of structural repairs. The National Centre for Historical Memory, the government agency in charge of historical memory nationwide, also promised to help digitalise the logbooks and store copies in its archive.

Saving Colombia’s painful memories

Colombia’s government has been, as JusticeInfo told, seriously reconstructing what happened and redressing victims since a decade ago, meaning the country has been in the peculiar situation of implementing transitional justice measures even as the armed conflict raged. Just the National Centre for Historical Memory has produced 102 book-length investigations over three different administrations, documenting human rights violations and diverse effects of the conflict, ranging from forced displacement, land dispossession, sexual violence and kidnappings to violence towards indigenous communities, local politicians, journalists or transgender persons.

At the same time, thousands of the country’s 9 million victims have been safekeeping documents, treasuring photographs and building personal archives since even before. Many such initiatives have gained international recognition. The files that Fabiola Lalinde laboriously kept detailing the disappearance and extrajudicial execution of her son Luis Fernando by Army officials in 1984 – which she dubbed ‘Operation Kingbird’, just like the diminutive bird that forcefully defends its young – were included in UNESCO’s Memory of the World register. The colourful collages made by the Mampuján Weavers, a group of women victims in Montes de María who resorted to cloth cut-outs to tell their stories of displacement, are now permanently displayed in Colombia’s National Museum and have travelled to museums in France and Canada.

In recognition of this, the 2016 peace deal included historical memory as one of the goals of Colombia’s 3-year-old transitional justice system, which includes a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) and a special tribunal. In the accord’s view, memory contributes to truth and redress, echoing the ideas put forward by former special rapporteur – and fellow Colombian – Pablo de Greiff in his reports to the UN.

State memory vs. community memory

Community-led initiatives feel that national and local governments value their work, but seldom provide financial or technical support to them. As a result, they rely on international donations to carry on, while being run by devoted volunteers and guarding vulnerable relics as best they can.

“We haven’t had almost any support since we were born in 2012,” says Orlando Carreño, co-founder of Valledupar’s Centre for the Memory of Conflict. His regional memorial has been closed since three years ago, when the political appointee at the departmental library kicked them out. They were only able to find a new home in a school this year, but the pandemic has forced them to postpone their reopening.

Most of their archive is hosted on their sleek website, which was funded by international donors. But they don’t have the means to upload the local vallenato songs detailing the armed conflict they compiled and published as a book-and-CD collection. “It’s not just about money. Imagine how useful it would be if the National Archive offered us training in archival cataloguing and conservation,” he adds.

It’s a view shared by most of the 30 local memory sites nationwide, which got together to create the Colombian Network of Places of Memory. “For years we were abandoned. We were close to throwing in the towel because we couldn’t afford it and grew tired. Even broken roof shingles we’d have pay from our pocket,” says school teacher Alba Gelpud, who cares after the small museum in El Placer, a rural hamlet in Putumayo that was the epicentre of an infamous paramilitary massacre.

Their precarious existence has led them to suggest an overhaul of the National Historical Memory Museum, a long-postponed promise whose first stone was laid in February. “Instead of creating a centralised museum, we propose that the state supports regional museums. Or that we go through with building it, but make sure it’s not just a museum in Bogota but a network of them, and that long-standing regional initiatives get funding and support. That we don’t do this from scratch,” says Father José Luis Foncillas from Tumaco’s House of Memory.

Their view echoes the TRC’s mandate, which stipulates that the transitional justice system’s truth-seeking efforts must seek diverse sectors of Colombian society and shall inform the museum’s narrative.

“The state must commit not simply to preserving those versions of historical memory that align with governmental ideologies and institutional viewpoints. It must commit to publicly preserving and actively promoting a multiplicity of endeavours, especially those of victims—those citizens whose rights and safety the state has failed to protect”, says Greeley, who co-founded the Symbolic Reparations Research Project.

This would not only allow memory sites like Granada’s Hall of Never Again to survive, but also to ensure that Colombians have a plurality of views regarding what happened to them and therefore greater chances of fostering national reconciliation. As logbook author Consuelo López says, “this is a heritage we must protect, in hope that such painful events never happen again.”