By opening Gibril Massaquoi’s trial in Kerava, southern Finland, on February 1, the Finns look set to shake up international criminal justice habits and practices.

If the Finnish judicial authorities meet their goal, it will have taken less than three years to complete the Massaquoi case, from the time they received a complaint in 2018 to the trial court verdict expected this summer. This unprecedented speed puts to shame the international tribunals and other European countries also handling Liberian war crimes cases.

But that's not all. Faced with the always difficult task of trying foreigners for crimes committed thousands of miles away - according to the principle of "universal jurisdiction" - in a context that is totally foreign to it, Finland is innovating. The Liberian and Sierra Leonean witnesses will not have to leave their country, the court will come to them. Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, most of the hearings will be held directly on the spot, in Monrovia and then in Freetown, between February and April. This is a profound reversal of current practice in universal jurisdiction, which gives the right to try anyone, anywhere, for international crimes such as torture, war crimes and crimes against humanity. These trials traditionally take place in the host country.

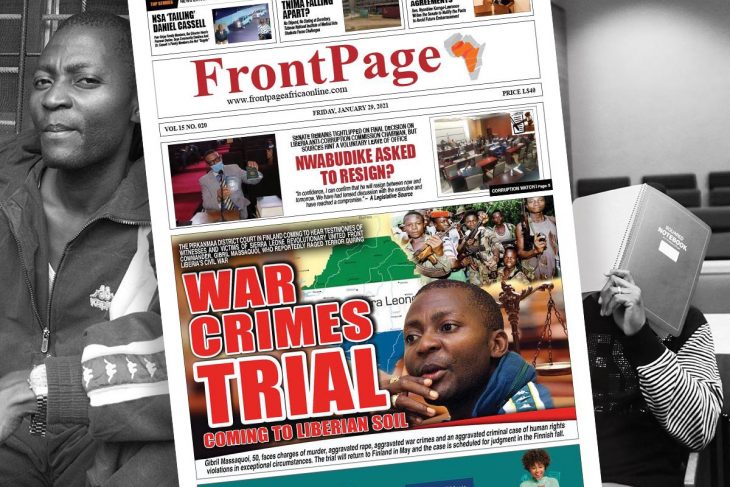

The Massaquoi case

Massaquoi is a former commander and spokesman for the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), a rebellion that ravaged Sierra Leone between 1991 and 2001. In Finland, he is accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity committed in Liberia between 1999 and 2003, when some RUF leaders had close ties to the then Liberian government led by Charles Taylor. Taylor, a key figure in the civil wars of the West African sub-region, was sentenced in 2012 to 50 years in prison by a UN court, the Special Court for Sierra Leone. Massaquoi was also a target of that international court some two decades ago, but to escape prosecution he agreed to become the chief informant for the prosecutor's office, helping the prosecutor arrest and convict his former brothers-in-arms. It was in gratitude for his services that he was granted asylum in Finland in 2008. But ten years later, NGOs informed the Finnish police of new charges against the Sierra Leonean, this time for crimes committed in Liberia.

The Finnish investigation started in October 2018. Fourteen months later, on March 10, 2020, Massaquoi was arrested. He discovered the fragility of the immunity he had enjoyed for 17 years. Thirty years after taking up arms, Massaquoi, 51, is to hear on Wednesday, February 3 the charges against him for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The Finnish model

Finnish investigators visited Liberia for several weeks in 2019 and 2020 - before and after Massaquoi's arrest - at the same time that Switzerland and Belgium were claiming they could not visit and neglecting their Liberian cases. But it is by choosing to relocate the court to Liberia and Sierra Leone, to hear most of the hundred witnesses heard by the police, that the Finnish justice system chose to change existing practice. Four judges, two prosecutors and one defence lawyer (the other one will remain in Finland with Massaquoi, who will be able to follow the hearings by satellite link) will travel to the Liberian capital Monrovia and the Sierra Leonean capital Freetown between February and April. They will visit sites that are at the heart of the case. Because of the pandemic, public access to courtrooms in Monrovia and Freetown will be limited, but video coverage of the hearings is to be organized.

For anyone who doubts the merits or feasibility of the proposed model, Finnish officials calmly explain that they have, in fact, already tested it. In 2009, the Finnish judiciary held its first genocide trial. To try Rwandan François Bazaramba, accused of crimes committed in Rwanda in April 1994, the court sat in Rwanda and Tanzania to hear 53 of the 68 witnesses in the case. The court visited the crime scene in Nyakizu. Bazaramba was sentenced to life imprisonment.

In a press release issued in June 2010, the court described some of the challenges of this type of trial: “The reliability of testimonies must always be evaluated in a normal Finnish criminal procedure and the trial concerning genocide has not made an exception in this respect. The linguistic and cultural differences and the political nature of the events under investigation have, however, made the evaluation exceptionally challenging in this trial. When evaluating the reliability of the testimonies, especially the significance of relay interpretation, the special characteristics of the African culture, the subordinate position of the witnesses in prison as well as the influence of conceptions formed in the gacaca proceedings and the influence of general political factors must have been taken into account.”

Contrast with Switzerland and Belgium

The Bazaramba case seems to have escaped the memory of experts in international justice, but this will perhaps be less so for the Massaquoi case. First, because it will be relayed by a coalition of European and American NGOs and university centres that have mobilized on this issue. Second, because the Massaquoi trial opens at a time when proceedings against Liberians - for crimes committed in the civil wars between 1989 and 2003 - have also been opened in the UK, France, Switzerland and Belgium. In the case especially of these last two countries, the Finnish example shows up their slowness, timidity and lack of innovation. After multiple postponements, the Swiss justice system is to reopen the trial of Alieu Kosiah on February 15, but this former Liberian warlord has been in prison for more than five years and Swiss investigators have never set foot in Liberia. The Belgian justice system has had a case pending for nearly seven years against a former commander of an armed group, Martina Johnson, and has not carried out any investigation at the scene either. French investigators, on the other hand, have made the trip.

There is one final argument that the Finns put forward to explain their strategy. It is a very pragmatic argument. In this country where the use of public money is taken very seriously, the judicial system has established that this method of working is the most financially efficient. Perhaps the Finnish lesson could also apply to international tribunals.