“This is the first time, perhaps in history, that an armed group makes peace, lays down its weapons, submits to a jurisdiction and within this jurisdiction, through its own accounts, contributes to truth-finding”, said the tribunal president Eduardo Cifuentes.

Three years after opening its doors and following two and a half years of investigation, Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP), the special tribunal stemming from the 2016 peace deal, unveiled its first indictment on Thursday, January 28, which ruled that kidnappings committed by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) constitute "war crimes" and "crimes against humanity". Despite the momentous occasion the courtroom was almost completely empty, as Colombia is currently undergoing a second serious wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

“This legal qualification is the highest reproach that this court can make and responds to the most serious violations of the principle of humanity,” underscored justice Julieta Lemaitre, who led the JEP investigation, during the live-streamed hearing.

The indictees, eight former Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) commanders, have now 30 days to ponder which road to navigate in the Colombian transitional justice’s two-track system. If they accept the court’s findings and acknowledge their responsibility, as well as contribute with the truth and personally redress victims, they can receive 5-to-8-year sentences in a non-prison setting. If they reject the findings, their case would move to an adversarial system and, if found guilty, would face 15-to-20-year prison sentences.

The JEP’s first case

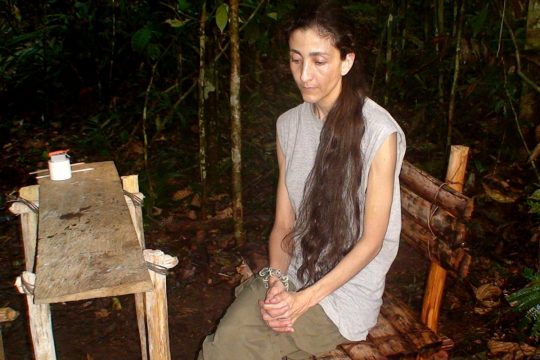

This “Case 01” is one of the first seven macro-cases opened by the transitional justice’s judicial arm and one of the two specifically focusing on FARC’s deeds. It is highly symbolic because kidnappings were for years that guerrilla’s most infamous practice, with haunting images of caged and chained prisoners in the rainforest garnering media attention worldwide and wide repudiation from all sectors of Colombian society.

In two years, the JEP documented the plight of 2,528 victims who are now accredited as parties to the case, including persons who were held in captivity by FARC for as long as 14 years and their relatives. It also used 17 reports submitted by different parties, including ten from victims and civic organisations, four from the Attorney General’s Office, two from the National Centre for Historical Memory and one from the Police. At least two of those came from organisations that have been highly sceptical of the peace accord and the transitional justice.

The JEP spoke at length with those standing accused. In lengthy confidential hearings and written testimonies, at least 283 former rebels – including 26 former members of FARC’s Central High Command – answered the tribunal’s questions regarding kidnappings. Hours of videos and hundreds of pages in transcriptions were then transmitted, as Justice Info told, to victims so they could confront their captors’ accounts. In total, 908 victims submitted observations and questions.

Three forms of kidnapping

After studying all of this material, the JEP’s Judicial Panel for Acknowledgment established in a 322-page document that FARC’s kidnappings between 1990 and 2012 can be divided into three broad categories or criminal policies, each of them driven by a different motivation.

In first place, the guerrilla kidnapped hundreds of persons with the goal of obtaining ransom for them, in what quickly became one of its main sources of funding. Although FARC spoke of identifying “enemies of the people” who had money and were therefore “financial objectives”, in practice they ended up abducting scores of civilians regardless of their age, their economic status or even whether they had already paid. It was, the tribunal concluded, “a policy that turned human beings into objects whose value did not lie in their human dignity, but in the money they could bring to the armed organization”.

Second, FARC kept hundreds of persons – especially soldiers, policemen and politicians - as hostages in a bid to pressure the Colombian government into exchanging them for rebels who were imprisoned. Finally, in regions where it sought to assert social and territorial control, FARC kidnapped hundreds of civilians and public officials. This included punishing persons they deemed as informants, scaring communities, hindering civil servants from performing their duties (like registering statistical information for the population census) and forcing locals to carry out tasks such as transporting food, providing medical care or building roads.

In its dossier, the JEP identifies specific examples of abductions carried out by every one of FARC’s military structures in each of those three categories. This information is the basis for its argument that all three kidnapping policies – for money, for human exchange and for territorial control - were both “systematic” and “widespread”.

Degrading treatments for all

As part of the JEP’s proceedings, former FARC rebels have begun admitting their responsibility and expressing their regret. But, as Justice Info told in this story, victims have been incensed by their captors’ failure to acknowledge the degrading treatments inflicted on them and the years of long suffering their families endured in their absence.

The tribunal’s report gives significant space to their physical and emotional plight. Among other patterns of behaviour, the JEP documents how victims were routinely insulted and humiliated, chained for years on end, taken on forced marches notwithstanding their medical conditions or physical limitations, prevented from having any intimacy, denied medical care and even subjected to mock firing squads.

The tribunal stressed that not only civilians were subjected to these degrading treatments, but also soldiers and policemen. This means that members of the military, although not strictly considered prisoners of war under IHL since Colombia’s armed conflict was not an international one, were considered by the JEP as victims of war crimes too.

Even though FARC leaders claimed victims were usually treated well, the tribunal sided with victims and argues that no internal communications show them inquiring about the state of those held in captivity. “The order of good treatment concerned only the preservation of captives’ biological life and not their human dignity,” the JEP concluded. In the court’s view, there is a deeply felt need among victims of seeing their former captors acknowledge the intensity of their suffering, as well as the long-term emotional toll on them and their relatives. Kidnappings were, in the JEP’s words, “a borderline situation that put all aspects of life in crisis.”

The JEP’s investigative effort allows a better understanding of the patterns of victimisation. After contrasting six different databases, it determined that at least 21,396 persons were abducted by FARC over two decades, with the brunt of them held captive during the failed peace negotiations between former president Andrés Pastrana and FARC, between 1998 and 2002. One of its most striking revelations is how many kidnappings had tragic endings: at least 627 victims (2,9% of the total) were murdered and another 1,860 (8,7%) are still deemed missing. Hence the JEP’s decision to order former FARC commanders to provide information to the Unit for the Search of persons deemed missing, which – along with the tribunal and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission - forms the transitional justice system.

Two major dilemmas

The JEP faced two major dilemmas in this case: what criminal charges to file against FARC and who to accuse, given that the Colombian transitional justice model seeks to prosecute at least those most responsible of the most serious crimes.

In the end, its justices chose to split the indictment in two stages. In this first decision they bring charges against the eight persons who formed part of FARC’s Secretariat, its highest circle of power, including former commander-in-chief Rodrigo Londoño, former peace negotiators Pastor Alape, Jaime Parra, Joaquín Gómez and Rodrigo Granda and current congressmen Julián Gallo and Pablo Catatumbo. One of them, Bertulfo Álvarez, died of cancer the day before the tribunal’s announcement.

In its decision, the JEP attributes command responsibility to FARC’s top brass. The court came to this conclusion after scouring hundreds of internal documents and questioning former rebels, establishing that the leadership of the strongly hierarchical guerrilla was personally responsible for approving sources of revenue and instructing its military structures on how to identify potential targets. It also determined that commanders were in constant communication with their troops and were unable to provide any proof of anyone being internally disciplined over degrading treatment.

“War crimes and crimes against humanity”

In light of this, the JEP accused them of the war crime of “taking of hostages” and the crime against humanity of “imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty”, as well as murder, torture, sexual violence, enforced disappearance, forced displacement and other inhumane acts. It also clarified that under Colombian law they were responsible for “extortive kidnapping” and “simple kidnapping”.

“These were not mistakes, these were war crimes and crimes against humanity,” said tribunal president Cifuentes.

The JEP made one more significant decision: it changed the case’s name to ‘hostage-taking and other serious deprivations of liberty’. In doing so, it dropped the term ‘retentions’ that FARC historically used and victims despised, given that they felt it undermined their dignity and justified their captors.

Throughout this year, the JEP will announce similar decisions detailing the actions by each of the guerrilla’s blocs, focusing on the roles and responsibilities of regional commanders and their subordinates. The reasoning behind this was that, as Justice Info told, those are the former rebels who are more knowledgeable of the truths victims want to hear.

The FARC leaders’ dilemma

What will the sanctions be against FARC leaders singled out in the JEP’s indictment? The answer to that question depends on whether they accept the tribunal’s charges or not. Given that they are the first on the docket so far, their decision is a major test for Colombia’s innovative transitional justice model, that seeks to strike a balance between retribution and redress.

In this two-track system, FARC leaders may receive a more lenient sentence if – and only if – they fulfil three conditions: they must acknowledge their responsibility, tell kidnapping survivors the truths they still long for and personally redress them. Accepting the JEP’s indictment would be a first step towards qualifying for a special sanction of 5 to 8 years in a non-prison setting, that would probably be decided this year. If they reject it, the case will be forwarded to the tribunal’s prosecution unit and a trial would ensue. Should they be convicted, they face sentences ranging from 15 to 20 years under ordinary prison conditions.

The idea behind this incentive is that persons can own up to their role, allowing the JEP to build its cases quicker than in an adversarial system. In turn, this should avoid the tribunal from collapsing on account of the enormous legacy of atrocities it has to prosecute in a country where 9 million persons – out of a population of 48 million – are officially registered as victims. A similar decision is expected soon on a second case, concerning extrajudicial executions carried out by members of the Colombian military.

Many questions still remain unanswered, including what the penalties will look like – something that, as Justice Info has told, the JEP is still due to flesh out - and whether FARC’s two indicted lawmakers may continue serving in Congress. And also whether the seven indicted former rebels might accept some of the charges and reject others, meaning the same case could end up moving along the two tracks – simultaneously.

“A very grave mistake”

Former FARC members have so far been silent on the content of the JEP’s indictment, signalling that they are studying it with their lawyers and underlining that they continue to consider it “a very grave mistake that we can only regret.” In the meantime, they seem to be paying closer attention to victims’ demands. A week ago, the political party they created announced it was changing its name, dropping the FARC acronym that victims profoundly resented and adopting the new moniker Party of the Commons.

The government of president Iván Duque, a critic of both the peace deal and the transitional justice system, has been mostly quiet on a decision that contradicts its narrative that the JEP would not bring serious charges against FARC rebels. It is, however, centring its critiques on the possibility that they receive non-prison sentences. “What’s at stake is that these sanctions are proportional and effective and do not result in the re-victimisation of those who suffered on account of those who committed these crimes not being punished,” said Duque, who emphasised that an accusation of committing crimes against humanity should not be compatible with political office.

Many victims recognise the decision as an important step, but are still mindful of FARC’s response. “Reading the way the JEP qualified FARC’s behaviour, reading the complexity of these crimes and their legal consequences, is for me a guarantee that we are not heading towards amnesties or impunity”, said Ingrid Betancourt, a former lawmaker who was abducted during her 2002 presidential run and remained kidnapped for six years. Four weeks from now, FARC’s former commanders will announce whether they own up to their crimes.